Lessons In Patient-Centricity From Rare Disease Clinical Trials

By Dalfoni Banerjee, 3Sixty Pharma Solutions LLC, and Paul Burke, Chaucer Life Sciences

Patient-centricity has been defined in various ways, but we like to think of it as simply “to identify and seize the opportunity to create value for patients — and to do so with patients whenever it’s feasible.” Pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies have begun to embrace the concept relatively recently. However, the idea — and practice — has been around for a long time in other industries.

Technology, automotive, and consumer product makers can offer insight into the concept of engaging the end customer in the ideation, design, and development of new products and services. For example, the innovation and design powerhouse IDEO uses a process termed human-centric design that engages people from the beginning of development to ultimately assure their problems are fully addressed. Other organizations use similar approaches, such as “design thinking,” to innovate, focusing on users’ experiences, especially their emotional ones, and by building empathy with users and customers. The tremendous success of this type of approach is well recognized in these industries.1

The biopharma industry is moving a bit more slowly toward patient-centricity, and there is a heightened awareness of the necessity for doing so. While many in the industry recognize that it is both good for the patient and good for biopharma, there remains reluctance in some corners. The industry has unique challenges, such as the regulatory landscape. Also, some question the need because novel therapies have been developed without patient centricity, so why change?

In a 2012 white paper, Aidan Nuttall elucidated the need for change, noting the following:

- Nearly 80 percent of all clinical studies fail to finish on time, and 20 percent of those are delayed for six months or more.

- Eighty-five percent of clinical trials fail to retain enough patients.

- The average dropout rate across all clinical trials is around 30 percent.

- Over two-thirds of sites fail to meet original patient enrollment for a given trial.

- Up to 50 percent of sites enroll one or no patients in their studies.2

The current state has worked well to create many innovative new drugs and diagnostics. Moving away from this is uncomfortable and (initially) an uphill climb. Momentum is needed to get over the "transition state" to the patient-centric future. This usually means significant investment of resources, time, and energy and strong, sustained leadership from very senior levels of the organization.

So, what can patient-centricity look like in the clinical trial arena? Well, there’s already a model that exhibits many of the elements of patient-centricity in clinical trials, and it’s in the rare diseases space.

Rare Diseases — A Brief Primer

First, a bit about rare diseases, because it will inform the remainder of the discussion.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), rare diseases affect more than 400 million people worldwide (approximately 6 percent of the population).3 The total number of Americans living with a rare disease is estimated at between 25 and 30 million.4 In Europe, the total is approximately 27 to 36 million,5 and in India, the estimate is a staggering 70 million.6

In the Orphan Drug Act of 1983, the U.S. Congress defined a rare disease as one that affects fewer than 200,000 people (in the U.S.).7 Due to the lack of interest from drug companies in developing treatments for rare diseases, such treatments became known as orphan drugs — and the Orphan Drug Act provided financial incentives that were meant to spur development.

Outside the U.S., countries have their own official definitions of a rare disease. In the European Union, a disease is defined as rare when it affects fewer than 1 in 2,000 people.8 WHO defines rare disease as one with a prevalence of 1 in 1000 people (or fewer).3

Per FDA requirements, at least one adequate and well-controlled trial (§314.126) is required for approval of an orphan drug, versus the standard of two such trials for non-orphan drugs.9 See the FDA list of Orphan Drugs.

Drivers Of Innovation: Patient-Centricity In Rare-Disease Clinical Trials

Drug development in the orphan drug space presents some unique challenges. With so few patients, true engagement is critical across the entire drug development life cycle, from clinical trials and regulatory approval to patient diagnosis and drug adherence.

The primary driver of innovation in the rare disease arena is the urgent need for new therapies in disease areas that are poorly understood by most healthcare professionals and that in many cases affect young children disproportionally. There is often a lack of basic research into patients’ conditions, and clear diagnostic guidelines may be lacking. The patients’ geographic sparseness adds to the difficulty of gaining the attention of the pharmaceutical and healthcare industries. Fortunately, patients and their families have inspired regulatory changes (including the Orphan Drug Act) that provide incentives for orphan drug research.

Patients with rare diseases often feel isolated, and many have responded by creating online and offline networks of “people like them” who share their experiences and collectively and individually become very well informed about their conditions. As such, they have also become influential with pharma companies, regulators, and payers.

They have also become experts, sought after by pharma to support targeted orphan drug development programs, even setting the research agenda, promoting collaborative research networks, initiating studies, and providing financial support.

Pharma companies have engaged patients to provide input into the design of clinical studies, study protocols, meaningful endpoint definitions, and benefit/risk assessments, as well as sharing study findings. The patients’ networks have helped operational support of clinical trials, such as in-patient recruitment campaigns. In many rare diseases, characterization of the disorder may be poorly developed, and patient advocates work closely with healthcare professionals to help refine definitions and what constitutes value to them in their treatment.

The essential, central role and value of patient engagement in orphan drug development exemplifies the benefits of patient-centricity. Strategies being adopted to enable adoption of a patient-centric approach to the broader drug development industry include:

- Acquiring and learning from the voice of the patient,

- Interacting with and engaging patients and patient organizations (in a compliant way) as true respected partners in the drug development process, and

- Seeking solutions to a range of patient problems uncovered by paying close attention to the entire patient journey.

Additional Opportunities: Patient-Centricity In Clinical Trials

The most obvious avenues (and, in some cases, low-hanging fruit) of “identifying and seizing the opportunity to create value for patients” have been executed by pharma companies: ensuring ease of swallowing, avoiding the provocation of the gag reflex by oral treatments, reducing the number of doses required for efficacy, and/or utilizing combination therapies, etc.

A major enabling force for patient-centricity in non-rare disease clinical trials is the emergence of several technologies to capture, store, and analyze patient data. This digital opportunity includes ePROs (electronic patient recorded outcomes), usually mobile/wearable devices. ePROs offer the potential for 24/7 real-time monitoring of key clinical measurements (e.g., heart rate, blood glucose levels) or via interactive patient assessment surveys and diaries. Data can be recorded in databases in the cloud, analyzed, and reported remotely. This type of approach can potentially be used for real-time efficacy and safety monitoring, as well as providing more operational data to support clinical trial management.

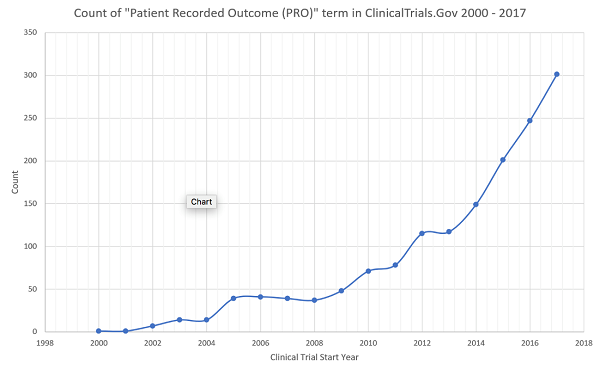

Patient insights can inspire new areas of clinical research or formulation decisions. Real-world evidence (e.g., from patient electronic health records) can help drive drug development and drive the choice of primary outcomes. Patient insights can improve clinical protocol design. During clinical trials, patient feedback can inform future treatments and drug modalities, as well as aid clinical trial recruitment and retention. Patient-recorded outcomes have become a very important component of drug development, as can be seen by the rising number of mentions of “PROs” in ClinicalTrials.gov over the last 15 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1

A Few Final Thoughts

Patient-centricity is essential for pharma for all the reasons discussed above. Regulators should set goals to incentivize change in this direction at industry, company, regulator, and payer levels. Pharma companies should help lead the change by weaving patient-centricity into the fabric of their cultures. As such, patient-centricity should be highly visible, well-funded, and embedded within the corporate innovation operating model. Finally, all entities within the industry should develop momentum and make patient-centricity a habit.

References:

- https://hbr.org/2015/09/design-thinking-comes-of-age

- https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/considerations-for-improving-patient-0001

- http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/priority_medicines/Ch6_19Rare.pdf

- https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/pages/31/faqs-about-rare-diseases

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4204590/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5754932/

- https://www.fda.gov/ForIndustry/DevelopingProductsforRareDiseasesConditions/HowtoapplyforOrphanProductDesignation/ucm364750.htm

- http://www.orphanet.org.uk/national/GB-EN/index/about-rare-diseases/

- https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/CFR-2010-title21-vol5/CFR-2010-title21-vol5-sec314-126

About The Authors:

Dalfoni Banerjee is an award-winning, solution-focused entrepreneur. Beginning her career over 25 years ago in academic, pharmaceutical, and biotechnology research laboratories, she went on to lead inspection-readiness efforts, drive clinical research and clinical operations, manage relationships between pharma and key opinion leaders, develop marketing strategies/tactics, and launch new drug products — across 12+ therapeutic categories. Banerjee is an invited speaker and moderator on a variety of topics, has authored and co-authored several publications, and has received over 30 awards.

Paul Burke a partner and head of Life Sciences for Chaucer. He has over 20 years of experience delivering change in life science companies around the world. His career began as a statistician, which has proven to be a great foundation for leading an organization that excels in data driven change. Burke’s pharma life began at Pfizer in the UK, before he moved with them to the U.S. He then joined Chaucer in 2007 and started the Chaucer Life Sciences business. As a leader delivering change in R&D, Burke has built many successful, motivated teams both internally at Chaucer and within its clients.

Paul Burke a partner and head of Life Sciences for Chaucer. He has over 20 years of experience delivering change in life science companies around the world. His career began as a statistician, which has proven to be a great foundation for leading an organization that excels in data driven change. Burke’s pharma life began at Pfizer in the UK, before he moved with them to the U.S. He then joined Chaucer in 2007 and started the Chaucer Life Sciences business. As a leader delivering change in R&D, Burke has built many successful, motivated teams both internally at Chaucer and within its clients.