Quick Tips And Hot Takes For Selecting Clinical Trial Technology

By Monica Roy, consultant

“Swirl” connotes numerous meetings, multiple revisits of information, absence of a decision-making framework, and, ultimately, inefficient decision-making that keeps key downstream activities in limbo. No stranger to swirl is the act of selecting a new clinical trial technology and vendor. Avoid swirl and select a new clinical trial technology efficiently with this clinical trial technology selection guide.

Types Of Clinical Trial Technology And Their Decision Makers

The timing and scope of adopting clinical trial technology are dependent on the technology in question and to which cross functional group(s) a company has allocated decision-making. Some examples are listed in the non-exhaustive list below:

- IRT

- The need is identified by ClinOps and/or supply chain when start-up is initiated for a new study.

- Different IRTs may be used by different studies, especially at smaller companies, so this selection is made at the study level.

- EDC

- The need is identified by ClinOps or data management when start-up is initiated for a company’s first study (if EDC management is not already outsourced to a CRO).

- The same EDC system is typically used enterprisewide, so this selection is made once and perhaps revisited every few years.

- eTMF

- The need is identified by ClinOps when company start-up is initiated for a company’s first study (to file internal documents, even if the majority of the TMF is outsourced to a CRO).

- The same e-TMF system is typically used enterprisewide, so this selection is made once and perhaps revisited every few years.

- CTMS and/or clinical workflow automation solution

- The need is identified by ClinOps when a company’s clinical trial portfolio has scaled to such a degree that manual (mostly spreadsheet-related) processes become onerous.

- The same system is typically used enterprisewide, so this selection is made once and perhaps revisited every few years.

- Subject recruitment identification tool

- The need is identified by ClinOps when a study is consistently not meeting enrollment targets and needs standard site recruitment to be supplemented by other approaches, or a study plans to recruit for a rare disease.

- Different tools may be used by different studies (or not at all), so this selection is made at the study level.

- AI-based protocol design tool

- The need is identified by clinical science at any time in a company’s lifetime.

- The same system would typically be used enterprisewide, across all study protocols, so this selection is made once, and perhaps revisited every few years.

- Data warehouse

- The need is identified by clinical systems upon a request from senior leadership for clinical science to provide highly specific, custom analytics for scientific decision-making.

- The same system is typically used enterprisewide, so this selection is made once.

Compiling A Clinical Trial Technology Selection Team

Once a tech need is identified, it’s important to create a team that represents all the stakeholders in the technology. Some of these stakeholders may be more involved than others or only involved in certain parts of the process. Examples of stakeholders include:

- Group with the business need

- Initiative owner: This person should drive and coordinate the entire process, including convening the selection team.

- Business group lead: This person is the head of the group experiencing the need. This person should identify and assign the initiative owner. This person may be a high-level end user of the technology as well.

- Key decision maker: This person holds the budget for the technology and agrees to the purchase and selection.

- End users (each type): These people use and benefit from the technology on a regular basis.

- Information technology (IT)/bioinformatics/clinical systems

- Quality assurance (QA)

- Data privacy

- Procurement

Involve at least one representative each from IT, QA, data privacy, and procurement, if these groups are typically involved at your company.

Note that these groups may have standard vendor evaluation processes that always need to be followed. (For example, procurement may require that vendors be registered in the company’s supplier portal, that formal RFPs always be sent, or that vendor evaluation checklists always be completed.)

Also note that at larger companies, IT/bioinformatics groups may have their own technology “road map” that they use to build the company’s technology ecosystem. Thus, they may need to understand how the technology being evaluated will fit into that road map. They may also be maintaining a data lake or warehouse that will potentially connect with the new technology.

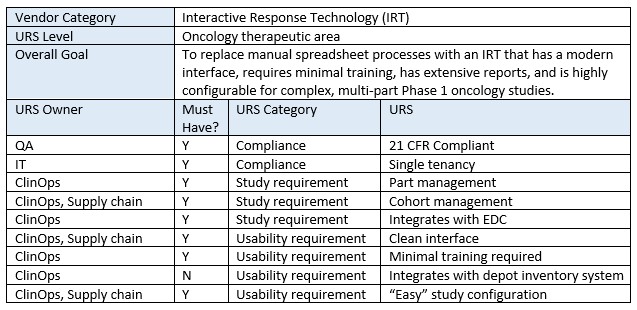

Defining Clinical Tech Specs With A URS

This is one of the most important steps, yet it is frequently skipped, especially at smaller companies: defining user requirements specifications (URS).

Unfortunately, teams sometimes jump into sourcing vendors and viewing demos randomly without a clear idea of what they’re really seeking. Teams selecting large technologies that will be used enterprisewide and have broad, general use (e.g., CTMS) are particularly prone to this.

There is something to be said about evaluating a vendor via an experienced gut reaction to what the vendor presents; however, this needs to be supplemented by a pre-discussed framework, such as a URS.

While clinical trial technology companies create URS for their own product (as mandated by 21 CRF Part 11), it’s just as important for clients of these companies to create their own URS document, i.e., a “wish list” for their ideal platform.

Creating a URS helps teams understand and document exactly how they wish their new technology will actually benefit them. Thus, this should not just be a list of technical features (in fact, technical features should be grouped into larger items) but should also include overall benefits and the user experience. This document need not be formal and can stay high level (unless company policy requires it). It also can be saved and reused by either the same team or other teams across the company. This task may initially seem time consuming, but once the team starts brainstorming, it can become creative and enjoyable. And once created, it makes downstream vendor evaluation tasks simpler and faster.

Remember, the goal is not to select the “best-in-class” vendor/technology. It’s to select the technology that is the best fit for your study and your company’s processes, philosophies, and desires. Below is an example excerpt from an IRT URS.

Where To Find And Who To Ask: Clinical Trial Technology Sourcing

These days, it’s easier than ever to source vendors and the overwhelming number of options may lead people to stick to the vendors they already know, regardless of quality, to shorten the selection process. However, following this guidance will help teams winnow vendors quickly, and once a vendor “type” has been identified, teams can source vendors in the following ways. Stay open minded, as what you seek may exist, but perhaps in a category of one and/or not fall into any of the traditional vendor categories.

- Colleagues (internal/external/previous) — Asking current or previous colleagues for their recommendations or thoughts on vendors can be a powerful, efficient way to learn of new vendors and obtain real, firsthand knowledge of a vendor’s capabilities and quality.

- Sourcing/Procurement — Company sourcing/procurement groups usually maintain a database of (prequalified, to a certain extent) vendors that teams can tap into.

- Digital/Clinical Innovation — Larger companies have digital innovation groups that are plugged into the more cutting-edge side of clinical trial technology and therefore may know of more innovative or deep-tech vendors. Using one of these vendors may give companies an advantage over the competition in terms of efficiency or other metrics.

- Supplier Diversity — This is another group that resides at mostly larger companies. They can recommend diverse suppliers (e.g., small, female, or minority owned) that you wouldn’t otherwise have heard of. Many large companies have supplier diversity targets (e.g., 10% of total annual spend), so by working with a diverse supplier, you would help the company meet its initiative and also support a diverse business.

- Conferences — Most industry conferences have a vendor floor that one can walk through and stop by vendor booths to learn more. Large conferences like SCOPE and DIA will give you exposure to the most vendors, but targeted ones like Clin Ops for Oncology Trials or Outsourcing West or East may expose you to more relevant vendors for your needs.

- Google — A web search is, of course, always available. However, for large vendor categories, this may bring up on the first page only the largest, most established players who have the most to spend on ads or creating lots of content that helps the site rank high in the organic listings. Thus, for companies seeking unique options, this may not be the best approach.

- Industry Publications — Subscribing to publications may expose you to and keep you in the loop regarding technology vendors through listings, paid articles, guest posts, etc.

- Pharma-specific marketplaces — Browsing pharma-specific vendor marketplaces (such as ClinEco and Health Sciences Collaborative) is another great option for those who prefer the online self-service approach to finding technology vendors. These cater to pharma audiences and so are more targeted than Google. Relatedly, those seeking consultants to drive or support their clinical technology initiatives can do a search on Clora or LifeSciHub.

Tips To Improve Clinical Trial Vendor Evaluation

Many companies already have a formal vendor selection process and will adhere to that, so the following guidance can be used as a supplement or inspiration for how to make the current process more efficient.

- After consulting the sources outlined above, the team should put together an initial list of no more than 10 potential vendors.

- The team should then create a shortlist of no more than five vendors with whom to schedule demos. One or more methods can be used for shortlisting:

- reviewing the vendor’s website for publicly available information to see if any vendors can be removed from the list (only do this if it’s obvious that they are not in the right technology category; otherwise, nuances may be missed)

- sending the vendors a request for information (RFI) (and non-disclosure agreement [NDA]), including some of the key URS items

- RFIs are less formal than RFPs and usually don’t include detailed costing, so can elicit faster responses from the vendor.

- emailing the URS items to the vendors directly and asking if they have the capabilities to address them

- scheduling 30-minute-or-less discovery calls to get a technology overview or clarifications

- Once the shortlist is created, the team should schedule in-depth, hour-long capabilities demos with the shortlisted vendors:

- At this point, the vendor should already have been informed of the team’s requirements.

- The team should inform the vendor that the team would like to be shown capabilities related to the URS before anything else. This guarantees that the features and benefits most important to the team are discussed thoroughly.

- The team should ask plenty of questions pertaining to the URS-related features to deeply understand if the features fulfill their needs and, if not, if they can live with the potential workarounds they will have to enact.

- This is also the time for the team to rely on gut feel and note if:

- the interface looks modern (using design thinking), is easy to navigate, and works for the team;

- the company and technology seem differentiated from or comparable to competitors in the space;

- the configuration process is commensurate with the complexity of the technology;

- the work required for users is balanced by the potential benefits;

- sufficient customer support will be provided for the team’s needs; and

- the team conducting the demo presented themselves professionally.

- Optional: After the demos, the team can ask each vendor for one or two references from companies similar to yours that can be emailed or called for quick feedback.

- Based on the proposals and the demos, the team should narrow the list of five vendors to no more than three.

- Next, the team should solicit proposals (including a budget) from each remaining vendor, either via email or a formal RFP.

Making The Final Clinical Trial Vendor Selection

Now that there are up to three proposals (including costs) in hand, the selection team should convene to make a selection based on impressions from the demos and the proposals, in relation to the allocated budget for the technology.

The selection team should then email the vendors the ultimate decision as it pertains to each.

Tech Selection Takeaway

In the pharma industry, it’s ironically common for people to complain about clinical trial technology not meeting their needs in an age of abundant tech options. Therefore, the real problem is finding and then matching the right technology to the right users in a way that’s efficient.

At the end of the day, technology is a tool, albeit one that can be leveraged for huge efficiencies. Some tools are built for specialization and others for general use. Others work well for certain types of users and processes yet not for others.

This is why it’s important to define up front what is important to your team, project, and company and what exactly you hope to get out of your technology. This way, you can make your clinical trial technology selection with confidence and success.

About The Author:

Monica Roy is a consultant and founder of a SaaS company with a clinical operations workflow automation tech platform, as well as an industry consultant. Monica has 20 years of experience working in clinical operations, primarily in oncology. She has led Phase 1 to 3 global trials across small and large pharma companies, with a focus on effectively leveraging process and technology to improve team efficiency and outcomes. Prior to that, she worked in preclinical research at UCSF, which resulted in publication authorships in the journals Neuron, Endocrinology, and others.

Monica Roy is a consultant and founder of a SaaS company with a clinical operations workflow automation tech platform, as well as an industry consultant. Monica has 20 years of experience working in clinical operations, primarily in oncology. She has led Phase 1 to 3 global trials across small and large pharma companies, with a focus on effectively leveraging process and technology to improve team efficiency and outcomes. Prior to that, she worked in preclinical research at UCSF, which resulted in publication authorships in the journals Neuron, Endocrinology, and others.