Teaching Old Dogs New Tricks: Can Competency With Clinical Research Technologies Be Enhanced?

By Beth Harper, Association of Clinical Research Professionals, and Wendy Tate, Forte

Many workplaces are composed of five generations, from traditionalists to Generation Zs.1 While this can lead to a host of communication, productivity, and other issues, the challenges are perhaps never more apparent than with the introduction and use of new technologies. In fact, this has led some to claim age isn’t the deciding factor when it comes to describing how proficient people are with digital technologies and culture. Instead, a new paradigm is needed that segments the workplace based more on technology exposure, comfort, and mindset than generation or age:2

Many workplaces are composed of five generations, from traditionalists to Generation Zs.1 While this can lead to a host of communication, productivity, and other issues, the challenges are perhaps never more apparent than with the introduction and use of new technologies. In fact, this has led some to claim age isn’t the deciding factor when it comes to describing how proficient people are with digital technologies and culture. Instead, a new paradigm is needed that segments the workplace based more on technology exposure, comfort, and mindset than generation or age:2

- Digital natives grew up with the Internet and are comfortable engaging in all digital channels.

- Digital immigrants have crossed the chasm to the digital world and have been forced into engagement in digital channels.

- Digital voyeurs recognize the shift to digital and are observing from an arm’s length.

- Digital holdouts resist the shift to digital and are ignoring the impact.

- The digital disengaged give up on digital and can be obsessed with erasing digital “exhaust” (the data trail left behind after online activity).

Seeking Insight Into Technology Competency

With the average number of apps used by the modern worker clocking in at 9.39, it’s no surprise that many employees are increasingly frustrated by information and app overload at work.3 With that as a background, we sought to better understand the impact a growing number of technologies is having on clinical research professionals. More specifically, we wanted to know what skills and training are needed to help the digital voyeurs, holdouts, and disengaged become more competent with the use of these technologies.

The Association of Clinical Research Professionals partnered with Forte (a clinical research technology and services provider) to conduct a survey to gain insights into the factors that contribute to technology competency and what, if anything, individuals, organizations, and technology providers can do to help a diverse workforce gain competency in the use of these technologies. The survey was deployed in early 2019, and during the course of six weeks, over 1,500 clinical research professionals responded. Of these, relevant data could be analyzed from 1,227 individuals’ responses. While the majority of respondents represented site personnel, approximately 20 percent were monitors, clinical research associates, or others working for sponsors and CROs. Collectively, their responses paint an interesting picture about perceived competency across 12 different types of technologies:

- Electronic data capture

- Interactive voice response/registration systems

- Clinical trial management systems

- E-regulatory tools (e.g., trail master file, site binders)

- Trial management portals

- E-source

- Wearable devices/sensors (e.g., health tracking wristbands, wearable glucose patches, wearable sensors)

- Participant payment systems

- E-clinical outcome assessment, electronic patient-reported outcomes

- Risk-based monitoring

- Investigator payment systems

- E-consent

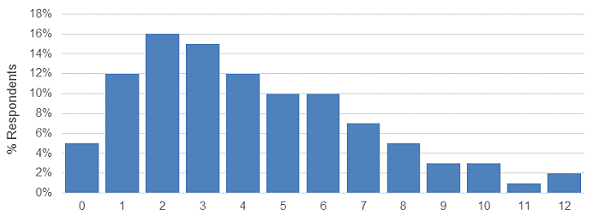

Figure 1: Number of systems used daily or weekly

Our results found that a small percentage of users are working with 12 different systems/technologies on a daily or weekly basis, but the median number of systems reported as being used daily or weekly was four.

Individuals ranked their perceived level of competency across four competency levels:

- Novice/beginner

- Developing/growing

- Proficient/competent

- Advanced/mastery

These levels were used to calculate a clinical research technology competency grade point average, which was used as the basis for the statistical analysis. Additional details on the methodology, analysis, and results will be forthcoming in future publications, so we are only sharing some key findings here. Recognizing that perceived competency may not equate to actual competency (which is a topic for additional research), the survey nonetheless revealed some interesting insights that may help debunk some of the myths about, and offer practical ideas for, enhancing competency.

At the high level, the vast majority of respondents — regardless of role or organization type — understand why clinical research technology is necessary to do their jobs (97 percent) and what is expected of them when it comes to using clinical research technology (93 percent). So that’s good news in terms of how the industry and management communicate and set expectations with their staff. But when it comes to receiving initial and ongoing training in the technologies, a critical and necessary component for competency, the picture isn’t quite as positive. Some 33 percent of respondents indicate they do not get adequate initial training, and 57 percent report they do not get ongoing continuing education with the technologies. Clearly this is a huge missed opportunity.

What Contributes To High Competency Levels?

The survey looked across multiple factors that we believe contribute to technology competency, including such things as:

- experience (years of clinical research and technology experience)

- systems/use (12 different types of technologies, daily/weekly use)

- navigation (comfort level, user interface, access)

- documentation (access, format)

- training (type, frequency, initial and ongoing, teaching peers/subjects)

- support (access, ability to find support, use of support)

- responsibilities/expectations (organizational mandates and policies, communication about technology/updates, use of technology for more efficient job function, workflow and team interactions).

Figure 2: Factors evaluated that influence technology competency

We found that differences in all areas were associated with differences in clinical research technology competency, except the documentation and support categories.

While expectations, communication, and good training are foundational requirements for technology competency, we found these specific factors made the biggest difference in terms of contributing to higher competency levels:

- The number of years of technology experience

- The number of systems accessed daily or weekly

- Feeling comfortable navigating the technologies

- Feeling comfortable teaching one’s peers

- Having access to on-demand, Web-based training

- Knowing how to interact with other people and teams using technology to get one’s job done

It’s no surprise that technology experience and exposure play a big role in terms of perceived competency. Just like foreign language immersion programs, simply being immersed in more technologies helps individuals feel more comfortable. Naturally those who feel more comfortable navigating the technologies and teaching their peers have higher perceived competency. That said, however, for the workforce segments that are more resistant or skeptical, we concluded there are a few things organizations and vendors can do to enhance competency. For the vendors, securing end-user input on both the user interface as well as the workflow (i.e., how one system fits into the overall process or workflow for the end users) is key. Further, ensuring users have access to on-demand, Web-based training so they can find information and get refreshed on the use of the technology is important as well. From an organizational standpoint, the more staff understand why and how to interact with others in the organization surrounding technology, the increased likelihood they will feel more competent.

As for the digital voyeurs, holdouts, and disengaged, it is incumbent on them to stay relevant in the workplace. Technology is here to stay, and resisting its use is an exercise in futility. They should leverage the promise of technology by taking advantage of the training available, immersing themselves, and adjusting their mindsets. Attitude, after all, is an equal if not more important component of the competency equation as knowledge and skills/abilities.4

So, at the end of the day, can clinical research technology competency be enhanced? Our survey results suggest the answer is a resounding yes. It’s not just a matter of waiting for the digital natives and digital immigrants to take over the workforce. And, it’s not necessarily easy. However, individuals, organizations, and vendors all play a role in enhancing proficiency with the growing number of promising technologies. We are optimistic about the results and look forward to sharing more insights and conducting future research in this area.

References:

- Grensing-Pophal, L. How to Handle 5 Generations in the Workplace. Feb 2018. Retrieved from https://hrdailyadvisor.blr.com/2018/02/26/handle-5-generations-workplace/

- Wang, R. Age Is Not The Deciding Factor In Five Generations Of Workers. Retrieved from http://blog.softwareinsider.org/2013/11/12/tuesdays-tip-understand-the-five-generation-of-digital-workers/

- Information and App Overload Hurts Worker Productivity, Focus and Morale Worldwide, According to New Independent Survey. September 2017. Retrieved from https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170918005033/en/Information-App-Overload-Hurts-Worker-Productivity-Focus

- Competency-based HR Management. Retrieved from: https://www.slideshare.net/ZainiIthnin1/competency-based-hr-management-18080989

About The Authors:

Beth Harper is the president of Clinical Performance Partners, Inc., a clinical research consulting firm specializing in enrollment and site performance management. Harper also is the workforce innovation officer for the Association of Clinical Research Professionals. She has passionately pursued solutions for optimizing clinical trials and educating clinical research professionals for over three decades. Harper is an adjunct assistant professor at George Washington University who has published and presented extensively in the areas of protocol optimization, study feasibility, site selection, patient recruitment, and sponsor-site relationship management. She serves on the CISCRP Advisory Board and the Clinical Leader Editorial Advisory Board, among other industry volunteer activities. Harper received her B.S. in occupational therapy from the University of Wisconsin and an MBA from the University of Texas. She can be reached at (817) 946-4728, bharper@clinicalperformancepartners.com, or bharper@acrpnet.org.

Beth Harper is the president of Clinical Performance Partners, Inc., a clinical research consulting firm specializing in enrollment and site performance management. Harper also is the workforce innovation officer for the Association of Clinical Research Professionals. She has passionately pursued solutions for optimizing clinical trials and educating clinical research professionals for over three decades. Harper is an adjunct assistant professor at George Washington University who has published and presented extensively in the areas of protocol optimization, study feasibility, site selection, patient recruitment, and sponsor-site relationship management. She serves on the CISCRP Advisory Board and the Clinical Leader Editorial Advisory Board, among other industry volunteer activities. Harper received her B.S. in occupational therapy from the University of Wisconsin and an MBA from the University of Texas. She can be reached at (817) 946-4728, bharper@clinicalperformancepartners.com, or bharper@acrpnet.org.

Wendy Tate is director of analytics at Forte. In this role, she collaborates with institutions to develop and validate meaningful and quality metrics regarding various aspects of clinical trial operations. Prior to Forte, Tate worked at the University of Arizona for 15 years, where she spent two years at the University of Arizona Cancer Center in clinical trials administration and more than six years at the center’s IRB, where she focused her efforts on operational metrics, process improvement, and compliance. She has a master’s degree in applied biosciences and a doctorate in pharmaceutical economics, policy, and outcomes, with a minor in epidemiology from the University of Arizona.

Wendy Tate is director of analytics at Forte. In this role, she collaborates with institutions to develop and validate meaningful and quality metrics regarding various aspects of clinical trial operations. Prior to Forte, Tate worked at the University of Arizona for 15 years, where she spent two years at the University of Arizona Cancer Center in clinical trials administration and more than six years at the center’s IRB, where she focused her efforts on operational metrics, process improvement, and compliance. She has a master’s degree in applied biosciences and a doctorate in pharmaceutical economics, policy, and outcomes, with a minor in epidemiology from the University of Arizona.