Digital Vs. Decentralized Trials: What's The Difference & How Do I Meet Implementation Challenges?

By Ben Alsdurf, TLGG Consulting

The traditional clinical research enterprise necessary for the development of new medical technologies is plagued by high costs, lengthy timelines, and inefficient processes. These inefficiencies drive the steep prices of new medical products and lead to inequities both in participation in clinical trials and, in turn, which demographic populations are best served by new medical technologies. Digital clinical trials (DCTs), a recently emerging paradigm that has gained even greater momentum since the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, have the potential to address many of the inefficiencies of traditional trials, enabling improved experiences for research participants and offering a wide range of benefits to product developers and other clinical research stakeholders. However, to implement and scale this approach, product developers will need to accommodate shifts in their operational models, embrace new technology, and forge new partnerships.

Defining Digital Clinical Trials

Most simply, DCTs are defined as trials that use novel digital technologies or processes to enable participation outside of conventional clinical settings. DCTs are guided by several core principles, including decentralizing access to trial participation, participant-centric design, efficiency of processes, and interoperable systems.

Digital vs. Decentralized

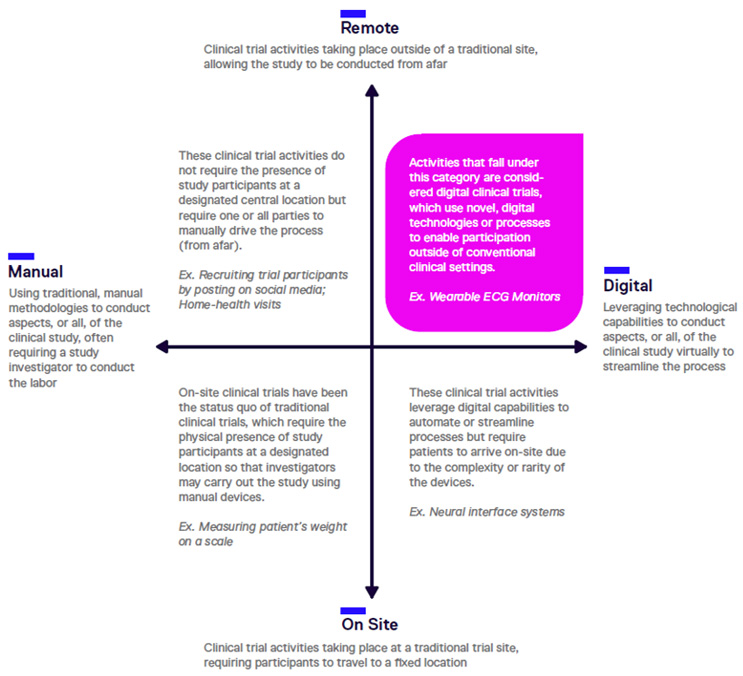

The terms “digital clinical trial” and “decentralized clinical trial” are often confused. Decentralization refers to enhancing participants’ ability to access a trial, regardless of their physical proximity to the trial center(s). While decentralization is a core principle of DCTs, all means of decentralizing research aren’t necessarily digital and not all digital tools can be used in fully decentralized ways.

For example, using social media as opposed to traditional methods to help drive recruitment to a trial is an example of leveraging a digital tool to aid the research process; however, one can use social media to help recruit for trials that adhere to centralized and analog designs and operations or for DCTs. Similarly, a trial may use digital tools that are exceedingly complex or practically unable to be moved from or used outside a trial center—a neural interface system, for example. While such a tool is digital, it does not contribute to decentralizing the trial. Digital trials tend to be at the forefront of individual medical technologies; today, that often means leveraging technologies like digital biomarkers and wearable medical monitoring devices.

Clinical trials can be understood on dimensions of remote vs. on-site participation and digital vs. analog, or manual, tools. At the intersection of digital and decentralized, we find DCTs.

Unlocking The Potential Of DCTs

The traditional clinical trial process is lengthy, expensive, prone to failure, and fails to equitably recruit and, in turn, successfully develop products for, some of the most vulnerable populations with acute medical needs. Inefficiencies of traditional trials include:

- Cost: Clinical trials accounts for nearly 40% of the U.S. pharma research budget, totaling approximately $7 billion per year.1

- Length: The full clinical trial phase of a product’s development can take a decade or longer.

- Failure rate: Only one in 10 drug candidates that enter Phase 1 trials will ultimately be approved by the FDA.2 Eighty-five percent of all clinical trials fail to recruit enough patients3 and up to 50% of trial sites enroll one or no patients in their studies.1 Roughly one-third of Phase 3 clinical studies are terminated because of enrollment difficulties.4 The high failure rates of drug candidates are the leading drivers of the costs to launch a new drug.5

- Inequity: Demographic groups such as persons of color and the elderly are disproportionately excluded from clinical trials. For example, an estimated 40% of all cardiology clinical trials exclude older adults,6 despite older age being a well-established factor associated with cardiovascular risk. These gaps result in decreased likelihood that complications of experimental products in such populations will be identified during trials, as well ensuring the needs of these populations remain underrepresented in product development.

DCTs offer opportunities to significantly improve all these dimensions of clinical trial performance by leveraging technology to reduce barriers to recruiting, retaining, and communicating with clinical trial participants, as well as opening new opportunities for data collection and analysis. Implementing DCT tools and approaches can benefit trials in several ways:

- Reducing burden on trial participants: The primary benefit of DCTs, from which many of the other benefits flow, is the reduced burden on trial participants. Digital tools enable more trial activities to be completed at home or in local sites, reducing the need for site visits. Digital communications tools and platforms also enable more frequent and robust communications between researchers and participants. Addressing these issues removes or reduces many significant barriers to trial participation and grows the pool of realistic potential participants for a given trial.

- Improved ability to recruit and retain participants: Making use of digital tools, including social media and video, can expand the reach of trial recruitment activities and increase and enhance communications between researchers and participants. By improving processes like informed consent and increasing the ability of researchers to address participants’ questions and reservations about participating, trial sponsors can recruit more participants from more diverse regions and demographics and better address communications gaps that contribute to the failed recruitment or retention of trial participants.

- Improved diversity of trial participants: Decreased reliance on centralized locations for recruiting participants and reducing required visits to trial centers allows trials to expand the geographies from which they recruit. The reduced physical burden for participants also makes it easier for older individuals or those with underlying health issues to participate in trials.

- Improved data collection and analysis: Digital tools can streamline data collection and enhance researchers’ abilities to collect more and diverse real-world data. The ability to share these data across interoperable networks creates new opportunities to inform and improve future research, interact with electronic medical records to proactively recruit participants and improve health outcomes, and recognize emerging data patterns in real time. Tools such as digital biomarkers, digital twins, and advanced AI can be leveraged to meet these goals, while reducing trial participant burden.

- Reduced cost and increased speed of trials: By increasing recruitment and retention of trial participants and improving and streamlining operations, DCTs offer the potential to enable more trials to be completed, and those trials to be completed more quickly.

Challenges and Implications For Implementing DCTs

Scaling and implementing DCTs will impact business and operating models for various clinical research stakeholders. With the DCT model continuing to gain momentum, product developers would be wise to embrace the trend, and forecast and prepare for some of the main challenges to more widely adopting this model.

Evaluating Suppliers & Partners

Deciding to adopt DCT approaches and tools means that a product developer will have to forge new types of partnerships and relationships with new suppliers of digital tools and services. One of the core capabilities required to effectively make this transition is to develop systems and rubrics to evaluate the various vendors who offer products and services that can be used to scale DCT. To address this challenge, product developers should look to develop in-house expertise while also taking advantage of tools in the public domain. For example, the Digital Medicine Society (DiME) has created a digital health vendor assessment for clinical trials.7

Incorporating Technology Expertise Early In Trial Design

Digital medical technology is evolving rapidly and dynamically. When planning trials, it will become increasingly important to integrate up-to-date understanding of technology into those plans, as the decision whether to use specific digital tools can influence aspects of the trial, including, but not limited to, timelines, recruitment strategies, types of data collected, and trainings required for research teams and partners.

To effectively leverage the potential of DCTs, product developers will need to develop expertise on how to integrate existing tools, such as digital biomarkers. Additionally, organizations will need to understand where digital technology can and cannot support their efforts when planning research. In some cases, this may even include forecasting how environments, including regulatory dynamics, are likely to change over the course of longer studies. Product developers should consider both developing in-house expertise in these areas and tapping external consultants and advisors with specialized areas of relevant experience and expertise.

Balancing Technology And The Human Touch In Trial Operations

The increased use of digital tools in clinical research will also create new operational considerations when carrying out studies. One area of particular importance will be training not only staff but also trial participants on the use of various technologies and devices. By decentralizing research through reliance on digital technology, trial participants become more responsible for data collection and therefore must be trained to use trial technologies effectively, to troubleshoot when needed, and to be aware of any safety and ethical considerations relating to the technologies they’re asked to use.

Related, trial sponsors will need to understand and predict the questions and problems that may arise for trial participants and provide tools to address them. One such challenge will be ensuring the appropriate balance of technology and human touch when providing tools for trial participants. For example, to ensure optimal participant experience and optimize retention, it is important to determine which types of user problems can be effectively addressed by a link to an FAQ, as opposed to when a (perhaps virtual) face-to-face with a member of the study team would be needed. To effectively meet these needs, product developers will have to adopt learnings from industries with greater focus on user experience and integrate those learnings into their operations. Once again, building these capabilities can be accomplished both in-house and through partnerships with consultants and advisors.

Vision Is Prerequisite, But Implementation Determines Winners

The continued growth of DCTs presents tremendous potential for researchers, trial participants, and the world at large. Clinical research stakeholders including product developers, patients, CROs, universities, hospitals, and digital entrepreneurs and experts will be affected as DCTs disrupt the current clinical research ecosystem. Those who proactively position themselves to thrive in the DCT space will be rewarded with opportunities for increased business development and gained efficiencies, while those who fail to adapt to the trend risk losing their current place within the clinical research landscape. Understanding the potential of this shifting landscape is only the first requisite to realizing its potential; strategic and effective implementation will determine the long-term winners in the DCT space.

References

- Nuttal, Aidan. (n.d.). Considerations For Improving Patient Recruitment Into Clinical Trials, Retrieved March 23 2012, www.clinicalleader.com/doc/considerations-for-improving-patient-0001.

- BIO, et al. (2015). Clinical Development Success Rates 2006-2015. Biotechnology Innovation Organization, www.bio.org/sites/default/files/legacy/bioorg/docs/Clinical%20Development%20Success%20Rates

%202006-2015%20-BIO,%20Biomedtracker,%20Amplion%202016.pdf. - BioPharma Dive. (2019, January 29). Decentralized Clinical Trials: Are We Ready to Make the Leap?, www.biopharmadive.com/spons/decentralized-clinical-trials-are-we-ready-to-make-theleap/546591/.

- CB Insights. (2021, June 11). The Future of Clinical Trials: The Promise of Ai and the Role of Big Tech. CB Insights Research, CB Insights, www.cbinsights.com/research/clinical-trials-ai-techdisruption/.

- Kate Smietana, et al. (2015, June 12). Improving R&D productivity, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, pp 455–456, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26065405.

- Farkouh, M. E. & Fuster, V. (2008). Time to welcome the elderly into clinical trials. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovas. Med. 5, 673–673.

- Erwin De beuckelaer, et al. (2021). Digital Health Vendor Assessment for Clinical Trials, DiMe Publications, https://hxlsales.s3.euwest1.amazonaws.com/DIGITAL+HEALTH+VENDOR+ASSESSMENT.pdf.

About The Author:

Ben Alsdurf is healthcare practice lead, U.S. at TLGG Consulting and has helped organizations of various sizes manage innovation initiatives, develop investment strategies, and plan for digital transformation. As the first employee of Amgen’s Berlin Technology and Innovation Hub – a corporate innovation center focused on emerging digital health technologies – he helped lay the groundwork for partnership screening and identification of emerging technology to support commercial innovation priorities. Previously, he was senior manager for external affairs with TB Alliance, a biotech using public-private partnerships and a virtual R&D model to develop new TB therapies. In that role he oversaw fundraising, business development, and strategic partnership initiatives. Connect with him on LinkedIn.

Ben Alsdurf is healthcare practice lead, U.S. at TLGG Consulting and has helped organizations of various sizes manage innovation initiatives, develop investment strategies, and plan for digital transformation. As the first employee of Amgen’s Berlin Technology and Innovation Hub – a corporate innovation center focused on emerging digital health technologies – he helped lay the groundwork for partnership screening and identification of emerging technology to support commercial innovation priorities. Previously, he was senior manager for external affairs with TB Alliance, a biotech using public-private partnerships and a virtual R&D model to develop new TB therapies. In that role he oversaw fundraising, business development, and strategic partnership initiatives. Connect with him on LinkedIn.