A Guide To Guidelines: How ICH And Others Help Us Conduct Better Trials

By Kamila Novak, KAN Consulting

Apart from clinical trial regulations, there is a plethora of nonbinding guidelines released by regulatory agencies and other organizations to guide the conduct of clinical trials. These include the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) and the World Health Organization (WHO). In addition, there are standards issued by organizations such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) and best practices published by TransCelerate Biopharma Inc. and the AVOCA Group. Regulations, guidelines, standards, and best practices form a unified ecosystem in which each influences the other. Regulations may be further elaborated in guidelines, especially those released by regulatory agencies, while guidelines and standards often refer to related regulations to provide additional information. Some can eventually become regulations, e.g., ISO 14155 for conducting studies with devices or CDISC data standards for clinical data outputs.

Since guidelines represent current thinking on a topic and are not legally binding, what should we do with them? Some regulated organizations take them extremely seriously, the same as regulations, and implement them in their standard operating procedures (SOPs) and work instructions (WI). A minority of organizations virtually ignore them. Most companies are somewhere in between these two extremes.

So, how much attention should we pay to guidelines? What role can they play in our work?

Why We Need Guidelines

Regulations are usually general and rarely change. They have the power of law and do not offer a choice whether to comply with them. At the same time, most of them do not include details or advice on what companies must do to comply with them. Therefore, agencies issue recommendations — also called guidelines — that elaborate on various topics. Guidelines are short, detailed, and narrow in scope. They may include advised steps for implementation and examples of use cases. Typically, their drafts are provided for public consultation before finalization.

At the same time, guidelines acknowledge their limitations related to the present knowledge and use of technology— that is why they refer to the contents within as “current thinking.”

Therefore, agencies and other issuers of guidelines encourage companies to think critically when deciding whether they apply to their business operations before embedding them into their SOPs.

ICH Guidelines In Action

ICH guidelines are the most comprehensive set of guidelines, covering preclinical and clinical development as well as post-marketing safety of medicinal products. They fall under four main categories: quality, safety, efficacy, and multidisciplinary (QSEM). Most of us are familiar with ICH E6 Good Clinical Practice (GCP). Medical writers know ICH E3 Clinical Study Reports, statisticians understand ICH E9 Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials, and pharmacovigilance experts follow ICH E2 A–F Pharmacovigilance. With the release of ICH E6 (R3), the awareness of ICH E8 General Considerations for Clinical Studies is growing. But what about the other ICH guidelines that might support a clinical trial?

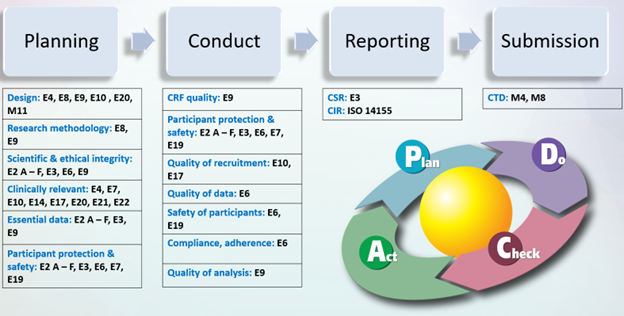

Let us consider a theoretical Phase 3 clinical trial. Which ICH guidelines can help us from start to finish? We can imagine the trial process as it coincides with its supporting guidelines, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. ICH Guidelines – A Clinical Trial Process View

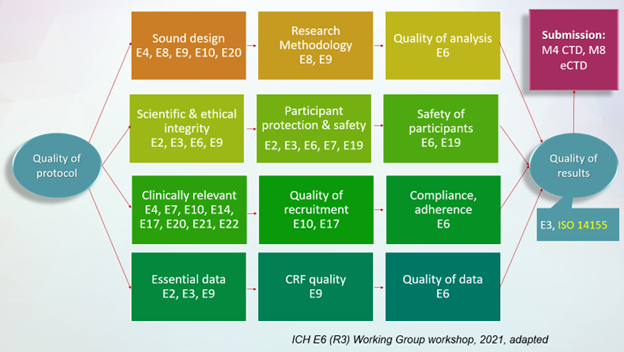

Alternatively, we can apply an objective-driven approach and look at our trial, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. ICH Guidelines – An Objective-Driven View

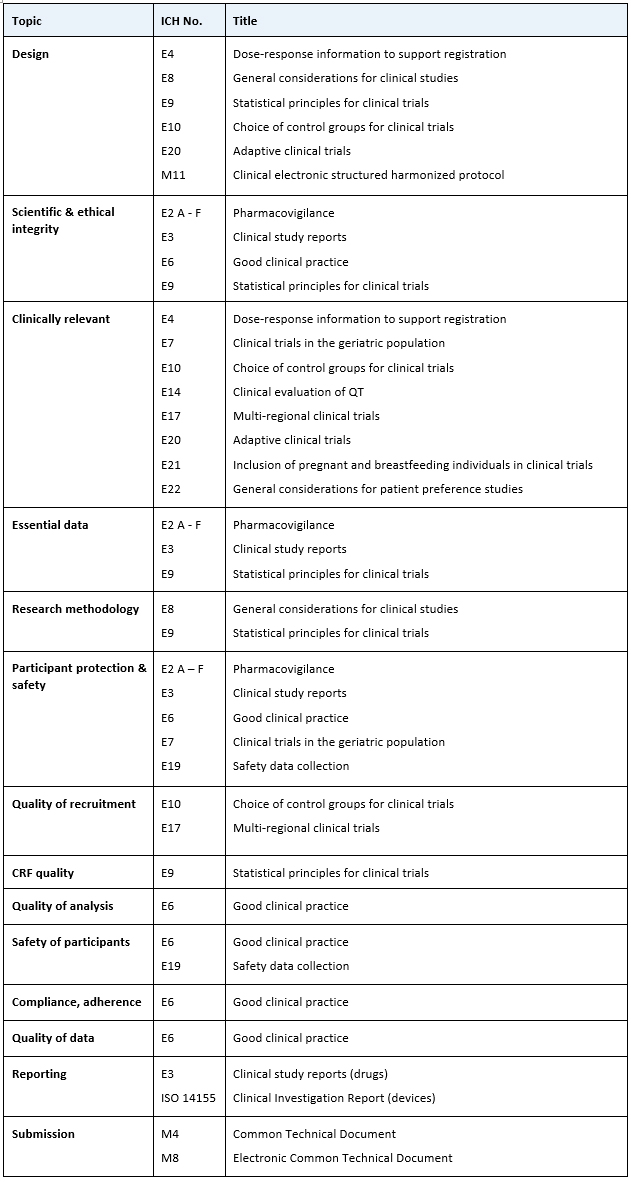

The list of guidelines is the same in both cases; only the vantage point differs. Since nobody is going to memorize the guidelines' titles, we can create a cheat sheet like the table below to help us.

Table 1. ICH E6 family guideline cheat sheet

Almost all guidelines belong to the efficacy family, except for submission, which comes from multidisciplinary, and one ISO standard, ICH 14155, which is the equivalent of Good Clinical Practice for medical devices.

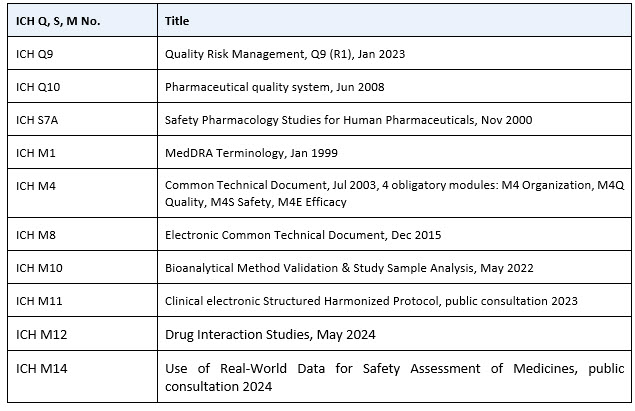

We should not forget to look at ICH guidelines outside the efficacy family and add more, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. ICH Q, S, and M guideline cheat sheet

Finally, to avoid confusion and ensure we use standardized terms and definitions in our SOPs, WIs, and clinical trial records, we can add the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) Glossary of ICH Terms & Definitions, regularly updated, with the current version 7 issued in October 2024. For special cases, we would also route our steps to the ICH safety family.

It’s important to mention that the ICH guidelines have been developed primarily for clinical research in countries that have the capacity and capability to follow them. However, only 23 countries are ICH members and an additional 41 are observers, which means there are about 100 countries outside the ICH, many of them low- and middle-income ones. What should they do with the guidelines? According to the WHO recommendations in “The Impact of Implementation of ICH Guidelines in Non-ICH Countries” published in 2002, they should use them for awareness, reference, and guidance purposes for national regulatory authorities when producing national legislation, as well as for education and training. They should not copy-paste them in regulations or within local companies’ SOPs without carefully considering their capacity and specifics.

Many Guidelines Require Many Hands — And Technological Support

This rather extensive list indicates that we need multidisciplinary teams to design good trials. Statisticians, with their knowledge of estimands elaborated in ICH E9 (R1), ask the right research questions, define endpoints, and derive corresponding variables. Medical experts including healthcare providers can help verify clinical relevance using the appropriate guidelines for a specific study, ensuring scientific and ethical integrity, participant safety, etc. Medical writers and regulatory experts support alignment with guidelines for study design and protocol structure to ensure the development of a clear, concise protocol that will empower data managers to generate fitting case report forms (CRFs) and clinical operations experts to produce sound study plans. A well-designed protocol is a prerequisite for good study. Collecting the right data will produce reliable results that we can use either for further decision-making for product development or for submitting a marketing application.

Many of these steps require individual expertise and are also still manual, but their future success lies in incorporating technology, specifically, the Clinical electronic Structured Harmonised Protocol (CeSHarP). CeSHarP is essentially a database, not a record; however, it can be made narrative like we are used to seeing with study protocols. CeSHarP has two purposes. One is the variability of its output, creating different views for different users. The other is the ability to create data flows and workflows, such as generating the clinical database, i.e., the CRF. From there, once trial data are collected, it generates the outputs for statistical analysis and study report, and, eventually, the common technical document for marketing authorizations.

However, this is a work in progress that ultimately uses the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR®) platform, bringing together ICH specialists, regulators, sponsors, and technology experts, who periodically report progress and milestones during workshops and webinars. If you add the potential of AI to help find the right study sites, improve recruitment, detect protocol deviations, data anomalies and outliers, clean adverse event and concomitant medication data, and more, then manually-driven, laborious, and lengthy clinical trials that often fail to achieve their objectives are now part of a new ecosystem of interoperable data flowing from start to end with the right “face” for each user. The goal is to have well-designed trials conducted more efficiently, thus bringing new therapies faster to patients who need them.

Conclusion

With all this technology, we need experts with critical thinking and deep knowledge who can make the right decisions and spot any technology issues. No job in clinical trials is likely to be eliminated, but most of them, if not all, will be transformed. Continuing professional development is not a luxury but something essential that employers provide for their employees. Perhaps we can start by reading guidelines related to our functional area, then expand. Reading the actual regulations and guidelines — not just their interpretation in company SOPs — will provide context, better understanding, and improved compliance.

References:

- The Impact of Implementation of ICH Guidelines in Non-ICH Countries, WHO 2002, https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/67272/WHO_EDM_QSM_2002.3.pdf

- Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use https://ich.org/

- International Organization for Standardization https://www.iso.org/home.html

- Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium https://www.cdisc.org/

- TransCelerate Biopharma Inc. https://www.transceleratebiopharmainc.com/

- AVOCA Group https://www.theavocagroup.com/

- Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources, FHIR https://fhir.org/

Author’s note: All figures and tables are taken from my presentation “A Guide to ICH Guidelines in Clinical Trials” delivered at the Drug Information Organization and the Society of Quality Assurance in 2025.

About The Author:

Kamila Novak, MSc, has been involved in clinical research since 1995, having worked in various positions in pharma and CROs. Since 2010, she has run her consulting company, focusing mostly on GXP auditing. She has first-hand experience with countries in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and North America. Kamila chairs the DIA Clinical Research Community and the SQA Beyond Compliance Specialty Section, leads the DIA Working Group on System Validation, serves as a mentor at the SQA and the DIA MW Community. In addition, Kamila is a member of the CDISC, the European Medical Writers’ Association, the Florence Healthcare Site Enablement League, the Continuing Professional Development UK, the Association for GXP Excellence, and the Rare Disease Foundation. She publishes articles and speaks at webinars and conferences. She received the SQA Distinguished Speaker Award in 2023 and 2024, and the DIA Global Inspire Award for Community Engagement in 2024. She and her company actively support capacity-building programs in Africa.

Kamila Novak, MSc, has been involved in clinical research since 1995, having worked in various positions in pharma and CROs. Since 2010, she has run her consulting company, focusing mostly on GXP auditing. She has first-hand experience with countries in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and North America. Kamila chairs the DIA Clinical Research Community and the SQA Beyond Compliance Specialty Section, leads the DIA Working Group on System Validation, serves as a mentor at the SQA and the DIA MW Community. In addition, Kamila is a member of the CDISC, the European Medical Writers’ Association, the Florence Healthcare Site Enablement League, the Continuing Professional Development UK, the Association for GXP Excellence, and the Rare Disease Foundation. She publishes articles and speaks at webinars and conferences. She received the SQA Distinguished Speaker Award in 2023 and 2024, and the DIA Global Inspire Award for Community Engagement in 2024. She and her company actively support capacity-building programs in Africa.