Clinical Events Classification: Past, Present, And Future

By Renato D. Lopes, M.D., Ph.D., and Matt Wilson, RN, Duke Clinical Research Institute

Clinical events classification (CEC) — a scientifically rigorous, systematic, comprehensive, unbiased, blinded, and independent assessment of clinical outcomes, particularly for studies that span regions and clinical settings — is a critical step in clinical research. CEC is essential to secure U.S. Food and Drug Administration or European Medicines Agency approval for drugs and devices in many therapeutic areas, such as cardiovascular, nephrology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, infectious diseases, oncology, pediatrics, and respiratory medicine.

The First Decade Of CEC: Proving Value

Adjudication of clinical trial events was first done as early as the 1940s. However, today’s form of CEC originated in the 1990s, based on the vision of Robert Califf, M.D., and Kenneth Mahaffey, M.D., who applied this approach to verify accurate clinical outcomes in randomized clinical trials for the first time. In the 1990s, CEC was a paper-driven process, with a focus on cardiovascular trials, and with medical records being translated into English on-site. During this decade, researchers relied on investigators to inform them about events.

One of the first studies where CEC was performed was the Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial (VALIANT) trial, which recorded a total of 1,700 fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarctions (MI) in 14,703 high-risk patients.1, 2 Events were recorded entirely on paper.

The Platelet 2b/3a Antagonist for the Reduction of Acute coronary syndrome events in a Global Organization Network (PARAGON)-B study provided additional proof of the value of adjudication.3 Here, 1,736 of 5,225 (33 percent) patients had suspected MIs, of which the CEC adjudicated 483 (28 percent) as MIs. In 404 patients (23 percent), the investigator and CEC assessments of MI differed; 270 MIs were identified by the CEC but not the investigators, and 134 were identified by investigators but not the CEC.4

The Second Decade: Electronic Records Added To Paper Ones

During the second decade of CEC, from 2000 to 2010, electronic medical records were increasingly added to paper ones, and CEC was applied in an expanding number of therapeutic areas. Adjudication was extended beyond investigator-identified events, and ancillary data such as laboratory results, symptoms, and procedures were taken into account for outcomes identification as well as for final classification. Additionally, retrospective adjudication efforts have been applied in some cases at the request of regulatory agencies. Certified translation vendors launched their businesses, offering a consistent service for global trials, and standards in outcome definitions began to surface.

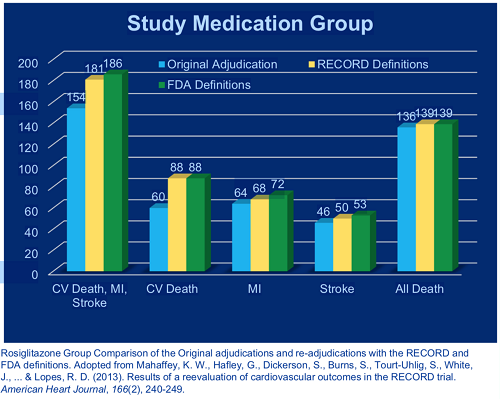

One example is the comprehensive retrospective review of the Rosiglitazone Evaluated for Cardiac Outcomes and Regulation of Glycaemia in Diabetes (RECORD) study (Figure 1). The trial showed rosiglitazone to be inferior to comparators (metformin or a sulfonylurea) for cardiovascular death and cardiovascular hospitalization. In September 2010, the FDA decided to allow continued marketing of rosiglitazone but required comprehensive reevaluation of death, MI, and stroke events in the study. The retrospective review revealed an increased number of primary endpoints, confirming the importance of systematic event identification and up-front data collection and query processing. Queries of death events resulted in the cause of death being changed for 5.5 percent of cases, and for MI and stroke, adjudication results were changed in 2.9 percent of cases, and no prior adjudication was found in 11.4 percent of cases.

Figure 1: Re-adjudication of the RECORD trial

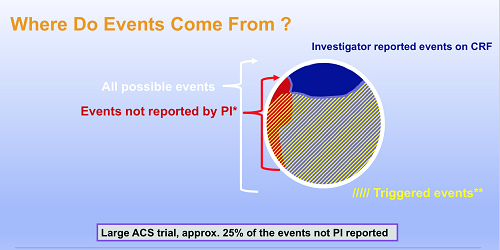

The Phase 3 Apixaban for Prevention of Acute Ischemic Events-2 (APPRAISE-2) trial also offers an example of the value of CEC during this period. The placebo-controlled study was designed to evaluate apixaban, a novel anticoagulant, and it planned to enroll almost 11,000 patients with a recent heart attack. Based on CEC findings, the trial was terminated prematurely after recruitment of 7,392 patients because of an increase in major bleeding events with apixaban and the lack of a signal of efficacy.5 This was one of the early uses of “trigger” methodologies to find evidence that an event may have occurred (Figure 2). Here, an edit check code is attached to the data that identifies a suspected event for adjudication for the duration of the study. This approach involves looking beyond investigator-reported events and designing the case report form to record ancillary data that could help identify unreported events.

Figure 2: Triggered events

The Third Decade: Fully Electronic Adjudication

Today, adjudication is fully electronic, data security is at the forefront, and innovations are being made in response to new technology platforms and evolving definitions of outcomes. Consideration of how safety and efficacy outcomes are defined, reported, and monitored accurately in a given study has led to development of integrated systems, processes, and operations. Translation vendors are more predominant, responding to increasing numbers of global trials.

Increasingly efficient trigger methodologies continue to evolve, helping to avoid creation of unnecessary noise during data collection. “Casting the right net” by including suppression rules to avoid having multiple triggers for the same event is also important.6

During the third decade of CEC, it is becoming important to reduce the risk of negatively adjudicated events (NAEs) — a clinical endpoint that is adjudicated as “no” — due to insufficient source documentation. In one recent study adjudicated by the DCRI, 11,890 events were triggered, including 1,342 NAEs. In general, the main reasons for NAEs are:

- The event truly does not meet the definition in the protocol

- Another event (not an endpoint) happened, such as a serious adverse event (SAE) which could have an alternate causal pathway to the event reported

- The reviewer did not have enough information to adjudicate the event due to insufficient source documentation.

NAEs might be a concern because they can suggest insufficient information to allow the appropriate adjudication, which can be associated with the quality of study conduct. In addition, regulators view them as a risk to quality due to the potential to miss serious adverse events that might not have been reported otherwise.

In future, CEC will increasingly use algorithmic adjudication and machine learning, with computers being trained to identify and classify potential clinical events. Pilot studies of this approach are currently underway, offering the promise of improved efficiency and accuracy in the CEC process, leading to streamlined and potentially less expensive clinical studies.

References:

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109705027981

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa032292

- http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/105/3/316

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11835026

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1105819

- http://www.cbinet.com/sites/default/files/files/Jones_Wilson_pres.pdf

About The Authors:

About The Authors:

Renato Lopes, M.D., MHS, Ph.D., is the faculty director and Matt Wilson, RN, is the operational director of Clinical Events Classification at the Duke Clinical Research Institute.