Common Issues And Trends In Clinical Research Vendor Qualification

By Kamila Novak, KAN Consulting MON. I.K.E.; Bernadette Bowen, consultant; Cecilia Matos-Rosa, Tonix Pharmaceuticals Holding Corp.; Dawn Niccum, SQA board member; and Judy Zahora, Tyra Biosciences, Inc.

In 2023, the topic of clinical vendor qualification became a recurrent theme during monthly meetings of the Society of Quality Assurance’s (SQA) Beyond Compliance Specialty Section (BCSS). Some BCSS members, mostly including auditors and clinical quality assurance (CQA) colleagues, agreed to face challenges with the (re)qualification of GCP vendors. From that conversation, a small group of volunteers gathered to develop and conduct a survey to collect industry data about current practices. Our objectives were to:

- Identify trends in the clinical vendor qualification process and best practices across the industry.

- Evaluate compliance of current practices with regulatory expectations.

- Examine common issues CQA professionals face regarding the qualifications of clinical vendors.

In this article, we use the term “vendor” as a synonym for “service provider.” Also, we use the term CQA unit, although not defined in regulations, since many pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies have established that function to focus on clinical operations and clinical trial conduct. A CQA unit may include one or more people, depending on the company size. Since not all organizations have CQA, the answer options in the survey were presented as CQA/designee.

Survey Development And Data Analysis

The BCSS and the SQA’s Clinical Specialty Section (CSS) collaborated to develop the survey, analyze collected data, and write this article. The survey was launched in the last week of August 2024. Data were analyzed during Q1 2025.

Survey Conduct

We shared the survey, “What are the obstacles and challenges encountered during initial assessments and reassessments of clinical Service Providers?,” with members of the SQA, the Drug Information Organization (DIA), and the public via posts in LinkedIn and direct emails to potential responders known by the survey team. The survey was anonymous; we did not collect any personal data. It closed on September 30, 2024.

Survey Results

We collected answers from 211 respondents representing sponsors (n = 93, 55.36%), consultancy agencies (n = 36, 21.43%), CROs (n = 26, 15.48%), and others (n = 13, 7.74%) including academia, technology providers, sites, specialized CROs, laboratories, biotechnology companies, and research centers. Respondents had to be engaged in clinical trial conduct to complete the survey; the survey closed if their answer was negative. Of the 211 respondents, 188 (89.10%) answered positively and completed the survey. We present the main results in this article and provide all results in Appendix 2 Survey results. The survey itself is provided in Appendix 3 Survey.

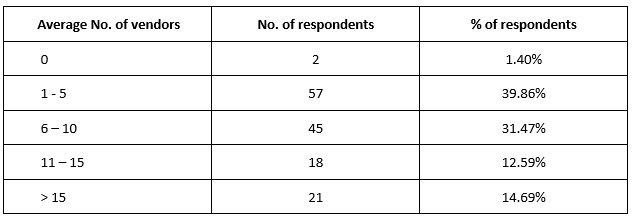

The number of vendors the organizations used in an average trial varied. One to five were used by the majority (n = 57, 39.86%) of organizations (Table 1).

Table 1. Average number of vendors used in clinical trials

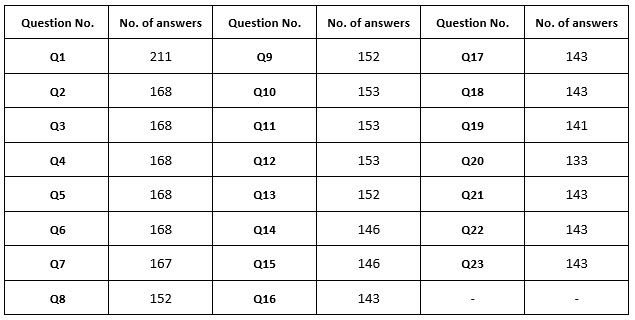

The survey setup allowed skipping answers; hence, the number of respondents differed for each question (Supplementary table 1).

Ninety percent (n = 152, 90.48%) of organizations had a CQA unit or equivalent, 50% (n = 88, 50.0%) had a vendor management department or role, and more than 90% (n = 153, 91.62%) had standard operating procedures (SOPs) describing vendor qualification and management. In 90% (n = 137, 90.13%) of organizations, the SOPs required vendors to be assessed or audited by CQA/designee prior to the start of work.

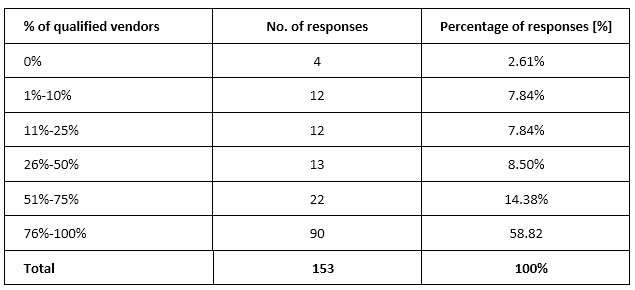

As for the percentage of vendors qualified prior to commencing work, almost 60% of respondents (n = 90, 58.82%) selected 76%-100%, and 22 (14.38%) selected 51%-75% (Supplementary table 2).

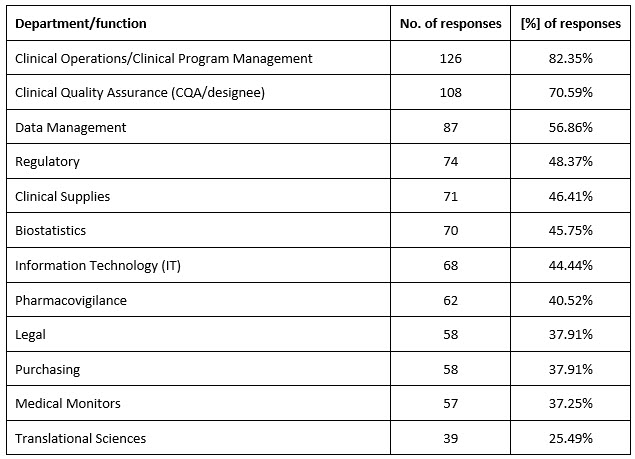

Over 90% of organizations (n = 142, 92.81%) used questionnaires, and 85% (n = 131, 85.62%) used audits. Clinical operations/clinical program management and CQA were involved in clinical vendor selection in most organizations (Supplementary table 3).

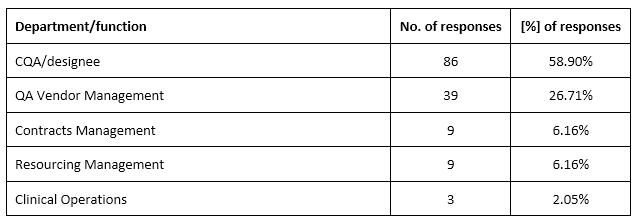

Ninety-six percent (n = 146, 96.05%) of organizations maintained a list of qualified vendors, and in almost all of them (n = 137, 93.84%), the list was accessible to CQA/designee and clinical operations. In most organizations (n = 86, 58.90%), CQA or QA vendor management (n = 39, 26.71%) was responsible for maintaining the Approved Vendor List (Supplementary table 4).

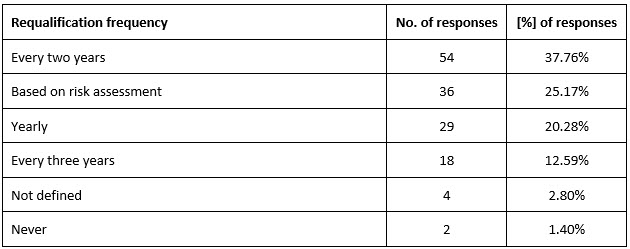

In 86% (n = 123, 86.01%) of organizations, clinical vendors were categorized based on risks. Clinical operations (ClinOps) teams shared quality concerns with CQA or anyone who was responsible for vendor qualification in 94% (n = 135, 94.41%) of organizations, and most of them performed requalification of high-risk vendors biennially (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of high-risk vendor requalification

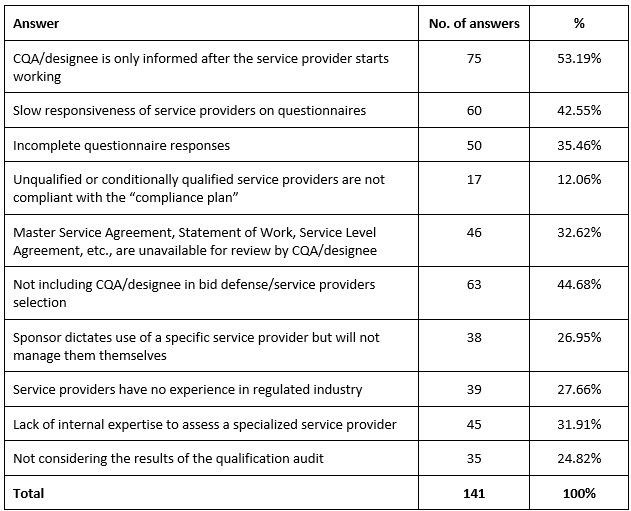

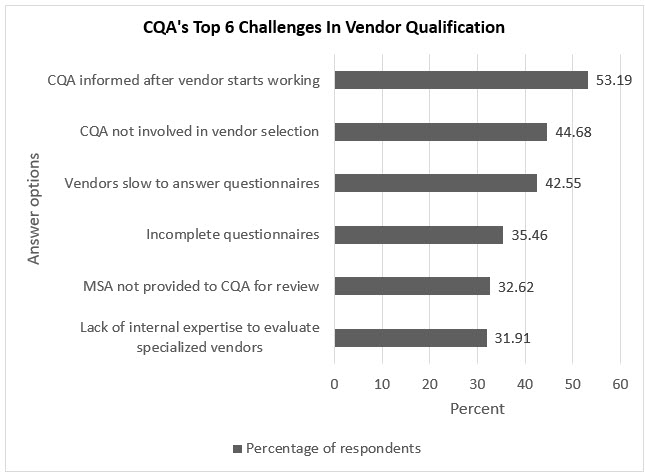

The next two questions asked about challenges and issues faced by the CQA. The biggest challenges encountered by CQA/designee regarding vendor qualifications were (Table 3, Figure 1):

- CQA/designee was only informed after the vendor started working (n = 75, 53.19%).

- CQA/designee did not participate in bid defense/vendor selection (n = 63, 44.68%).

Table 3. The biggest challenges encountered by CQA/designee regarding vendor qualifications

Figure 1. Top six challenges in vendor qualification faced by CQA

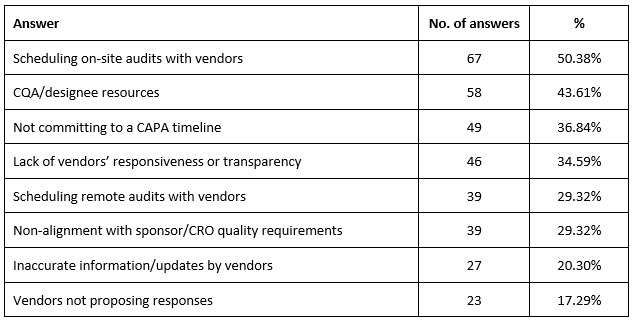

The biggest issues CQA encountered while scheduling/performing vendor reassessment were mostly related to scheduling on-site audits with vendors (n = 67, 50.38%) and CQA/designee resources (n = 58, 43.61%) (Table 4).

Table 4. CQA’s biggest issues with scheduling/performing vendor reassessment

In 60% (n = 87, 60.84%) of organizations, the CQA customized questionnaires based on the scope of work, while almost 35% (n = 50, 34.97%) used standard questionnaires.

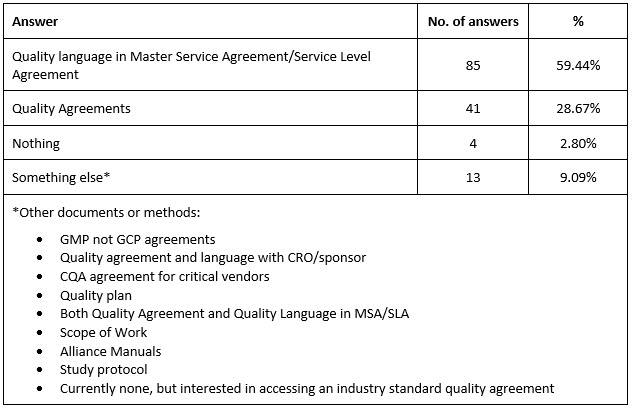

Most organizations (n = 85, 59.44%) used quality language in Master Service Agreement (MSA)/Service Level Agreement (SLA), followed by Quality Agreements (n = 41, 28.67%) (Supplementary table 5).

Discussion

The survey results indicate that most organizations have established processes and procedures for vendor assessments and qualifications aligned with best practices. However, some answers indicated that these practices are not always followed.

Observed issues and challenges

Although over 90% of organizations have SOPs for vendor qualification and management and require vendors to be assessed/audited by CQA before commencing contracted activities, less than 60% of organizations qualify at least 75% of their vendors before they start working, and in slightly more than half of them, CQA is informed only after the fact. This indicates a deviation from SOPs and potentially dysfunctional internal communication as well as a potential risk to the study, as CQA will not have the opportunity to evaluate a vendor’s QMS, lab facilities, etc. prior to the start of the contracted activities.

While almost 90% of organizations categorize vendors based on risk, only 25% leverage a risk-based approach to determine requalification frequency.

CQAs face issues with scheduling or performing vendor (re)assessments; over 50% are related to scheduling on-site vendor audits, and more than 40% of the issues identify internal resourcing issues, indicating that CQA units are understaffed.

Factors likely contributing to challenges:

- Deviations from SOPs requiring vendor qualification before work commencement, as well as omitting to timely inform CQA about new vendors may result from pressure to adhere to tight trial timelines and meet scheduled milestones.

- Another factor could be that many vendors agree to host in-depth audits examining their processes and procedures only after the contract is signed, and once signed, they begin to work.

- The third factor can be related to deficiencies in the organization’s quality management system (QMS). For example, if the quality issue definition for a study focuses on protocol deviations and serious breaches, then delayed vendor audits may not likely fulfill the definition criteria and adequate corrective and preventive action (CAPA) plans may not be developed. If a delayed audit is a quality issue but the root cause analysis (RCA) does not go deep enough or readily concludes it occurred due to a human error or technical failure, corrective actions will not address the true root cause, and the problem will likely recur. Often, organizations do not provide robust training on how to perform root cause analysis and develop effective CAPA plans; therefore, investigation outcomes stay on the surface and do not help to minimize issues in future.

- The fourth factor may be challenges in accommodating qualification audits on short notice without delaying the start of work.

- Limited budgets, cost-cutting measures, and hiring caps are likely to contribute to understaffed CQA units that in small organizations may include one person, often with other assigned responsibilities.

Many challenges and issues have a common denominator. Unlike the GMP area, where QA signature is required on most records and GLP where QA signs the QA statement, GCP guidelines and regulations do not require CQA signatures on records for submissions and/or under key operational decisions. CQA does not have any regulatory-derived authority regarding the selection and/or qualification of vendors, although organizational authority may vary from one organization to another.

Tips To Overcome Challenges

Some challenges can be easily resolved by analyzing and streamlining internal communication, clearly defining criteria for vendor qualification, and informing vendors that late and/or incomplete responses can result in disqualification.

Vendor contracts and agreements can include a clause stating that they become effective after a successful audit outcome, where “successful” should be precisely defined. If the audit results do not meet the criteria for success, the contract or agreement becomes null and void. This will help organizations to walk away from vendors whose performance will likely cause costly problems.

Companies can also create flexibility in the vendor qualification SOP by allowing vendors who need to start work immediately to do so with a written agreed justification. Then, an audit may be performed at a milestone, when there is enough evidence to evaluate whether the vendor works according to agreed SOPs.

Companies should also clearly specify quality issues and define late qualification audits for certain vendors after the work starts based on risk assessment and business needs to help improve SOP adherence. Periodic training on RCA and CAPA development using case studies can improve relevant skills, and such training will strengthen the health of the organization’s QMS.

Companies can also use risk-based approaches to vendor assessments and requalification frequency to better manage resource-intensive processes. Engaging external subject matter experts (SMEs) and contracting external auditors can boost CQA capacity. And while budget constraints can be difficult to overcome, using contractors as needed is generally more cost-effective than hiring new staff.

To mitigate the scheduling challenge and to minimize personnel time spent on supporting or hosting audits, some companies create virtual audit rooms where clients’ auditors can review typical qualification records and enter questions in shared trackers. Written answers are provided within 24 hours.

Finally, increasing both CQA’s role in the development of organizations’ policies and SOPs and executive management support will help demonstrate an organizational commitment to quality. Strengthening CQA’s role as active partners in vendor selection and qualification can decrease issues or their impact during study execution.

Limitations

This survey and answer analysis have limitations. The number of respondents was small; hence, we cannot generalize the results and conclusions to the whole industry.

Conclusion

While most companies have an established CQA unit and developed SOPs for adequate GCP vendor (re)qualification, based on the survey results, there are opportunities to improve the quality of both the execution of the vendor qualification process and the organizations’ QMS. These opportunities include applying the CQA audit program, creating fit-for-purpose SOPs based on risk assessment, leveraging a risk-based approach in line with current regulations and guidelines, and making internal communication more effective. Some of these opportunities need management commitment and support, but others are in the hands of the people involved. Strong (re)qualification processes have the potential to reduce operational issues and costs during the clinical trial conduct, as well as strengthen compliance with regulations.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ella Jou for co-developing the questionnaire and Debora Randall-Hlubek and Lisa Olson for reviewing all questionnaire drafts and providing valuable comments.

The authors would like to thank the Society of Quality Assurance for providing support to conduct the SurveyMonkey survey.

Conflict Of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The survey was developed and conducted anonymously and the results were analyzed on a voluntary basis.

Authors’ Declaration

The first draft of the article was written by Kamila Novak. All authors reviewed and edited drafts and approved the final version.

Appendix 1 Supplementary tables

Supplementary table 1. Number of answers per question

Supplementary table 2. Percentage of vendors qualified before commencing work

Supplementary table 3. Departments/functions involved in clinical vendor selection

Supplementary table 4. Departments responsible for maintaining the Approved Vendor List

Supplementary table 5. Types of contractual documents to ensure study quality

Note: Appendix 2 (survey results) and Appendix 3 (survey) are available upon request