Decentralized Clinical Trials: What Are The Opportunities For Data & Cost Savings?

By Justin Culbertson, RSM US LLP

Prior to the pandemic, most clinical trials were hybrid. As the pandemic continues, however, more activities are becoming virtualized, and trials are trending toward a fully decentralized model. With that said, a fully decentralized model still remains uncommon.

Among industry peers, sentiment remains positive that decentralized clinical trial (DCT) models will improve patient-centricity, reduce time to market for critical treatments, and reduce the cost of drugs to patients; however, some leaders have noted that the economic impact remains to be quantified.

A closer look is needed to examine if this transition to a more decentralized method is truly the change needed in the ever-evolving life sciences industry.

Clinical Trials Are Ripe For Efficiencies

When analyzing activity and potential investment opportunities in the clinical trial sector, typically there are several key metrics. Two of those metrics include clinical trial starts and average years to study completion. These metrics can signal efficiencies needed and perhaps areas that DCT models could address. So, what are the numbers telling us?

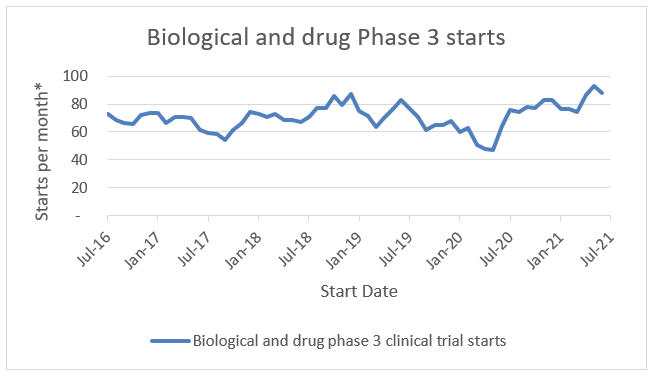

Clinical Trial Starts

Clinical trial starts have rebounded to or beyond their pre-pandemic levels. Three-month moving average biological and drug Phase 3 starts are up 36%, 6%, and 16% compared to the same metric one year, two years, and five years prior, respectively. As more trials start, sponsors and clinical trial administrators are evaluating the models that will set the stage for the future. DCT models could be the industry standard to address this growth.

*3 month moving average

Source: ClinicalTrials.gov; RSM US LLP

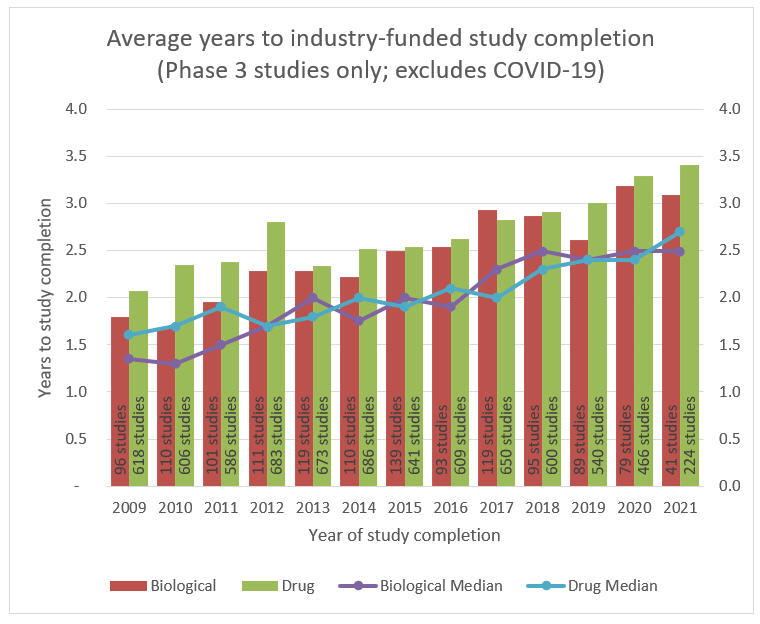

Average Years To Industry-Funded Study Completion

Highlighting the growing challenges with legacy clinical trial models, clinical trial durations have been increasing over the past decade as well. The average Phase 3 trial duration was approximately two years in 2009 compared to approximately 3.25 years now. This is attributed to increasing drug and treatment complexity as well as additional regulatory burdens. As discussed in the next section, this increasing duration could highlight the opportunity for DCT models as well.

Source: ClinicalTrials.gov; RSM US LLP

DCT Models Will Continue To Gain Traction Post-Pandemic

DCT models weren’t a foreign concept to the clinical trial industry prior to the pandemic; however, they also didn’t make up a significant portion of industry backlog. Based on an ERT survey, 33% of respondents indicated that they were conducting virtual trials prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly 73% of the respondents indicated that they now view virtualization of clinical trials as very or extremely important. Additionally, 82% of respondents indicated that they are now incorporating virtual components or fully virtualizing certain trials.

In the same survey, 43% of respondents identified patient recruitment and retention as the most significant challenge in the current environment. Almost one-third (32%) of respondents identified trial management as the most significant challenge.

As touched on earlier, life sciences organizations see possible benefits of decentralized and virtual interactions during trials. These benefits can range from the ability to develop algorithms to parse electronic health records and identify and recruit patients, which shortens the study startup timeline and reduces risk of failure due to non-enrollment, to remote monitoring, which eliminates scheduling of on-site visits and patient travel. In addition, many times a DCT approach improves data integrity, which shortens trial database closeout and reduces paperwork as companies look to clinical trial management software platforms to integrate sites.

The Cost And Quality Of Data

Biopharma executives recently ranked five factors in terms of importance when determining whether to decentralize parts of a clinical trial. In order from most important to least important, according to the report The Decentralized Clinical Trial Operating System, those rankings were:

- Cost compared to traditional methods

- Speed and efficiency

- Appropriateness and feasibility of DCT for specific therapeutic area

- Regulatory and compliance risks

- Quality of data

Most interesting in this ranking is that quality of data received the lowest importance ranking while cost and efficiency obtained the highest rankings. One might argue that quality of data significantly impacts each of the listed categories. With that in mind, perhaps quality of data should be moved up in this list. In a related question, and possibly indicative of the respondents’ views on the importance of quality of data, only 11% of biopharma executives indicated that they had integrated patient-collected data with great success (i.e., via wearable technologies), while 43% and 7% indicated that they had integrated with moderate or no success, respectively.

Let’s take a closer look at the impact of data quality on a clinical trial in terms of patient-related data and administrative data, and why it’s so important.

Patient-Related Data

Improving the quality of patient-related data increases a sponsor’s or trial administrator’s ability to improve patient-centricity. It also improves the quality of the decisions that are ultimately made related to drug and treatment approvals. To highlight the opportunities to reduce trial cost via improving patient-related data, note the following example of the use of wearables in a DCT setting.

Wearable devices in a clinical setting give a trial administrator the opportunity to obtain objective real-time data on a patient’s condition and improve the patient experience by lowering the frequency of travel to sites, which improves patient retention and reduces the cost related to new patient recruitment.

The Association of Clinical Research Organizations highlighted a case study with Covance that cited $10,000 to $25,000 as the cost to recruit a new patient without consideration for the cost of trial delays. While there are costs associated with implementing wearable technologies, such as purchasing the hardware, developing the software, paying for a SaaS subscription model, and more, these costs are significantly outweighed by costs to recruit new patient replacements.

In addition, using wearables has other operational advantages. For instance, the trial close-out activities related to database management are known laggers in the clinical trial process. It is not uncommon for a clinical trial administrator to spend three to six months or more on database closeout, significantly increasing the trial timeline. To the extent that real-time patient data can be gathered through the use of wearables, this data may be seen as less fallible than manually recorded data, thus reducing the time spent analyzing and reconciling related databases.

Administrative Data

CROs often experience one recurring challenge with administrative data. The contract closeout process and related billing reconciliations may take longer than intended. Similar to the database closeout timeline noted above, it is not uncommon for clinical trial administrators to spend three to six months or more reconciling their contract activities with their billings. This creates a period of uncertainty for clinical trial administrators and their biopharma sponsors. It is not uncommon for these processes to result in revenue true-ups or millions of dollars flowing to or from clinical trial administrators. As clinical trial administrators begin to leverage technologies that grant them real-time insight into site activity, such as clinical trial management platforms, this reconciliation process could be shortened.

Reimagining The Clinical Trial: Lessons Learned

Using the patient and administrative data examples above, it would seem that the costs of clinical trials could be reduced through improvements in the quality of the data, perhaps via a DCT approach.

Many people may view clinical trial cost and quality of data as two sides of the same coin. However, an executive’s perspective on the importance of the less-defined “clinical trial costs” compared to “quality of data” may influence their chosen path of DCT adoption. “Clinical trial costs” may be too nebulous compared to a more targeted area, such as “quality of data,” to result in meaningful change.

Some CRO executives have been reluctant to quantify cost savings related to DCTs. Quite possibly, this is due to the lack of historical data on DCTs; however, it may also be related to realized cost savings being below expectations. What could be causing this?

In Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee’s The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies, the authors explore electricity’s succession of the steam engine. They note the following:

“Years later, when that hallowed GPT electricity replaced the steam engine, engineers simply bought the largest electric motors they could find and stuck them where the steam engines used to be. Even when brand-new factories were built, they followed the same design. Perhaps unsurprisingly, records show that the electric motors did not lead to much of an improvement in performance…. Only after thirty years – long enough for the original managers to retire and be replaced by a new generation – did factory layouts change.”

They go on to state that these factory layout changes led to a doubling or tripling of productivity. The implication here is that organizational and process changes are often as important as the technological changes themselves. Sponsors and clinical trial administrators should look to reimagine their processes rather than view virtualization solutions as “bolt-on” improvements. Reimagining the DCT model will bring the efficiencies, and cost savings, they’ve been looking for.

Financial Reporting, The Often-Neglected Function

Often excluded from the DCT conversation are considerations related to a CRO’s financial reporting function. In fact, most guides on clinical trial decentralization do not include or mention these considerations.

For the past several years, large CROs have been operating under a new revenue recognition standard (ASC 606 – Revenue from Contracts with Customers). While this standard resulted in little to no change to the contracting process within CROs, it completely overhauled the revenue recognition process as companies went from measuring revenue based on the completion of units outlined in the contract to measuring revenue based on an estimated percentage of completion, typically calculated as actual costs incurred to date divided by estimated total costs of the clinical trial. The forecasting of estimated total costs has been supported by years of clinical trials performed under the legacy model, giving the companies a relatively straightforward and auditable estimation methodology.

The challenge with DCTs is that the cost model has now changed, potentially rendering the prior forecasting methodology obsolete when applied to DCTs. As a result, CROs will have to rely on new data to develop their forecasts as they continue their venture into the DCT arena. As fully decentralized trials are in their relative infancy, making up less than 10% of the industry backlog, CROs can expect less scrutiny from their auditors and financial regulators for the time being. However, they should expect increasing scrutiny as their project mix shifts from the legacy model to a decentralized model.

The Takeaway

Some clinical trial administrators have been reluctant to articulate the cost savings associated with a DCT methodology. With growing clinical trial starts and increasing trial durations, the industry needs a solution to reverse these trends and improve patient-centricity through reduced costs to patients. DCTs may be the solution; however, it may be a fallible perspective to consider DCTs or related virtual components as bolt-on solutions, versus holistically reevaluating and designing the clinical trial process with decentralization in mind. This evaluation process may be key to realizing the cost efficiencies expected from a DCT model.

About The Author:

Justin Culbertson is a director and senior life sciences analyst at RSM US LLP. He has more than 10 years of experience serving publicly traded and privately held companies through technical accounting and financial reporting services. He focuses on clinical research organizations (CROs) and similar service organizations in the life sciences industry. Justin has previously advised clients in the areas of new standard implementation, external audit, internal audit, risk management, mergers and acquisitions, process design and improvement, and internal and external financial reporting. He is also a member of RSM’s life sciences national industry leadership team.

Justin Culbertson is a director and senior life sciences analyst at RSM US LLP. He has more than 10 years of experience serving publicly traded and privately held companies through technical accounting and financial reporting services. He focuses on clinical research organizations (CROs) and similar service organizations in the life sciences industry. Justin has previously advised clients in the areas of new standard implementation, external audit, internal audit, risk management, mergers and acquisitions, process design and improvement, and internal and external financial reporting. He is also a member of RSM’s life sciences national industry leadership team.