Designing Quality Into Your TMF: ICH E6(R3) And Advancing Trial Efficiency

By Ken Keefer, MBA, PMP, Keefer Consulting Inc.

The May release of the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) draft guidance E6(R3)1 for public review and comment has inspired optimism that its implementation could lead to more efficient trials. Could implementation also improve trial master file (TMF) quality in support of greater efficiency?

A traditional focus on TMF quality control (document quality, completeness, and timeliness in filing) has helped TMF managers identify problems and assess readiness for GCP inspections. Now, more powerful information technologies are allowing regulators to view quality more broadly. ICH’s growing emphasis on quality by design (QbD) offers an opportunity to consider how TMF stakeholders’ needs are changing, including a shift in orientation from unstructured documents to structured data. Exploiting such changes could help sponsors better manage quality in the trials they conduct, resulting in greater efficiency and satisfaction of patient needs.

Quality By Design And The TMF

The quality improvement goals that sponsors establish influence who may benefit from them. The traditional view of TMF quality has been to satisfy regulators by retaining documents considered essential for them to assess GCP compliance. If a goal of TMF quality is to also increase trial efficiency, taking a QbD approach to improve TMF quality could involve additional stakeholders, especially those in study design and management roles who need information about current trial status and the events affecting progress.

This article relates QbD principles as advocated by J. M. Juran in the 1980s and 1990s2 to those promoted by ICH E6(R3) and its companion guideline E8(R1). Its intent is to suggest applying these principles to improve TMF quality while expanding its scope of use.

The ICH works with global regulatory bodies and industry groups to harmonize technical requirements worldwide. They do this by developing guidelines through consensus and recommending their adoption by regional regulators. Guidelines ICH E8(R1) and ICH E6(R3) are key to understanding how QbD is to be applied to clinical trial design and conduct.

ICH E8(R1), General Considerations for Clinical Studies3 refines the original E8 guideline by advocating QbD to proactively plan quality into the design of a clinical trial versus reactively relying on quality control (QC). E6(R3) describes what regulatory authorities are to expect of sponsors, investigators, and other parties collaborating in conducting a trial. It lists documents essential for all trials and others that may be essential in certain cases. It also provides criteria for sponsors to determine what documents are essential for particular trials.

E6(R3) defines “trial conduct” as "planning, initiating, performing, recording, oversight, evaluation, analysis and reporting." The placement of "planning" and "initiating" first underscores an emphasis on a quality planning process that identifies customers, their needs, and critical to quality (CTQ) factors before initiating a clinical trial. The guideline advises sponsors to consider inputs regarding trial design from a wide variety of stakeholders and to take a risk-proportionate approach in identifying CTQ factors. It also advises sponsors to ensure operational feasibility and to avoid unnecessary complexity, procedures, and data collection.

Both guidelines are subject to the Formal ICH Procedure, which culminates in adoption and implementation. Adoption of E6(R3) depends on implementation of E8(R1), which ICH adopted and recommended for implementation by national and regional regulators in 2021. Both the EMA and FDA have published E8(R1) as guidance for studies submitted to these agencies. The members of the ICH Assembly have now endorsed the draft version of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) E6(R3) and released it for public consultation under Step 2 of the Formal ICH Procedure.

Improving TMF Quality

Quality Goals

Juran argued that “[p]roduct features and failure rates are largely determined during planning for quality.” He defined a product as either a good or a service that is the output of a process. For example, a clinical trial is a service that tests the safety and efficacy of a therapeutic product. The trial protocol is an output of a study design process. The TMF service makes available outputs of multiple document creation and approval processes.

A product feature is a characteristic of a product designed to meet a customer need. Customers of a therapeutic product include payers, prescribers, and patients. Regulatory authorities are customers of trial data, including content documenting trial conduct. Features of a trial are methods and approaches intended to yield data that will gain regulatory approval. Designing processes to populate the TMF aims to satisfy regulators and avoid negative findings. Improving quality in this case usually incurs higher costs in the hope of gaining access to certain markets.

A product deficiency is the failure of a product feature to meet a customer need. A study design deficiency may be a failure to produce data of sufficient quality for a regulatory agency to make an informed decision regarding marketing authorization. Payers, prescribers, and patients may incur costs when product deficiencies arise after approval. Deficiencies can lead to customer dissatisfaction and raise costs, even if a product gains approval.

Quality Planning Road Map

Juran identified quality planning, quality control, and quality improvement as essential processes for managing quality. His approach emphasized planning quality at the outset to reduce the use of quality controls to detect and correct product deficiencies.

Juran defined quality planning as establishing quality goals and the means to meet those goals. He proposed a “quality planning road map” consisting of a series of steps. TMF planners may follow this approach to design TMF processes and to identify record locations and details governing transfers of content between systems as suggested in the TMF Reference Model “TMF Plan Template”.4 Sponsors already following a formal TMF process design approach may use the road map as a checklist to ensure observance of QbD principles.

Step 1: Establish quality goals.

Employing QbD to design and conduct more efficient trials and produce higher quality data could widen the scope of TMF quality goals for many sponsors. E6(R3) states that clinical trials should generate enough information of sufficient quality to support "good decision making." A TMF quality goal for complying with this standard might be to make documents available within time frames that would encourage more clinical trial stakeholders to rely on the TMF for information needed to design and conduct trials.

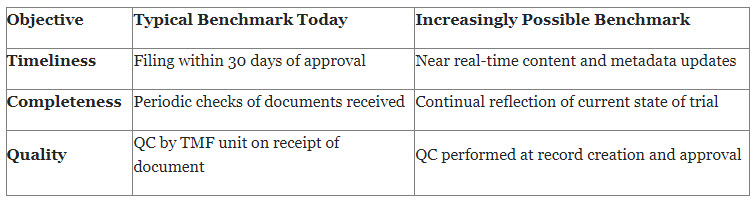

Quality planners should recognize that QbD, combined with evolving information technology and data standards, will increasingly allow for TMF benchmarks to approach real-time availability of content.

Step 2: Identify TMF customers.

Identifying all current and potential customers of TMF processes is critical if clinical and regulatory operations are to adopt the TMF as a management tool. Identification of customers may begin with those having roles defined in SOPs that currently govern the creation, approval, and filing of trial-related documents. Also important are potential customers who could benefit by using the TMF if it were to contain more complete and timely information. Study designers, study managers, and others directly responsible for trial outcomes would likely be among these beneficiaries.

Step 3: Determine customer needs.

An analysis of customer needs must answer two basic questions:

- What current customer needs must be satisfied?

- What are the needs of potential customers who could benefit if the TMF were to tell a more complete story of the trial?

For example, at least one study startup expert has stated that “QbD... provides an approach to identify risks many months before a protocol is approved,” substantially reducing the current average of eight months required for site start-up.5 Could study designers benefit by using the TMF if certain content were available earlier?

GCP inspectors generally consider TMF scope to include all essential documents, regardless of where they reside in one or more electronic or paper-based systems. Does the TMF Plan identify all systems containing documents an inspector might want to access?

Step 4: Develop product features.

Product (TMF service) features are CTQ factors that might include conformance to certain standards or the ability to store content and related metadata that communicates a trial's history. Such features might require changes to SOPs, or to software with the sponsor providing requirements.

Step 5: Develop process features.

Process features are CTQ factors required to produce product features. If a feature of the TMF was the capability to capture certain types of content earlier, could the TMF be created in time to receive it? What new benchmarks for completeness and quality to maintain inspection readiness could this make possible?

A common paradigm for planning TMF quality involves the functional unit in charge of the TMF setting quality control (QC) benchmarks and improving performance against those benchmarks. Other organization units often QC the same document before submitting it for filing in the TMF. Some sponsors involve stakeholders from other functional units in designing TMF processes, a cross-functional approach that can eliminate redundant steps. A cross-functional team might also ask what metadata could be captured during document creation.

Development of new capabilities might require collaboration with an industry standards body, such as participating in an initiative to enhance the CDISC TMF Reference Model to accommodate additional documents or metadata. Could new system interoperability standards support processes capable of producing needed TMF features?

Step 6: Develop process controls for transfer to operations.

Juran described a quality control as a set of activities to measure and compare actual process performance to quality goals and take corrective action when needed. Following a QbD approach should result in stronger, more efficient quality controls that meet customer needs. Would SOPs require revision or replacement to support redesigned process controls?

Closing

The ICH draft guidance E6(R3) offers an opportunity to better manage quality in clinical trials. Its emphasis on QbD points to an approach sponsors may follow to encourage adoption of the TMF as a trial management tool.

While TMF departments may employ Juran’s quality planning road map for the TMF service now, even greater benefits will become possible as sponsors implement E6(R3) and QbD throughout their organizations. Functional units at all organizational levels will be responsible for meeting CTQ requirements tied to strategic quality goals set by upper management. Trial design and TMF teams will collaborate prior to trial initiation in planning the features and processes necessary to meet CTQ requirements for customers of the trial and for customers of the TMF.

Until sponsors fully implement E6(R3) and QbD across their organizations, starting now could help TMF departments improve quality within their current scope of operations and enhance the capacity to serve an expanding base of TMF customers responsible for conducting clinical trials.

Resources:

- International Council For Harmonisation Of Technical Requirements For Pharmaceuticals For Human Use, ICH Harmonised Guideline Good Clinical Practice (GCP) E6(R3) Draft version, ICH, 19 May 2023, https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_E6%28R3%29_DraftGuideline_2023_0519.pdf, retrieved 14 Jun 2023.

- J. M. Juran, Juran on Quality by Design, 1992, New York, The Free Press.

- International Council For Harmonisation Of Technical Requirements For Pharmaceuticals For Human Use, General Considerations for Clinical Studies E8(R1), ICH, 6 Oct 2021, https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_E8-R1_Guideline_Step4_2021_1006.pdf, retrieved 14 Jun 2023.

- TMF-Plan-Template-v2-2022-10-21, TMF Reference Model, , 21 Oct 2022, https://tmfrefmodel.com/download/4789/?tmstv=1667384522, retrieved 21 Jun 2023.

- How will QbD require timeliness of filing documents necessary for study startup to the TMF?, Elvin Thalund, A Roadmap to Get Started With Quality by Design in Clinical Trials, Mar 2023, https://globalforum.diaglobal.org/issue/march-2023/?_ga=2.183728550.1273591766.1682094228-499071032.1643908408, retrieved 14 Jun 2023.

About The Author:

Ken Keefer founded Keefer Consulting Inc. early in his career with a commitment to helping clients develop innovative computer-based solutions to business problems. Today, he applies his experience to transforming clinical operations through improved system interoperability and process efficiency. He envisions a world in which clinical operations can share information seamlessly with regulators, service providers, and partners through common standards and processes. The ultimate goal is to achieve positive outcomes for patients quickly and cost-effectively.

Ken Keefer founded Keefer Consulting Inc. early in his career with a commitment to helping clients develop innovative computer-based solutions to business problems. Today, he applies his experience to transforming clinical operations through improved system interoperability and process efficiency. He envisions a world in which clinical operations can share information seamlessly with regulators, service providers, and partners through common standards and processes. The ultimate goal is to achieve positive outcomes for patients quickly and cost-effectively.

Ken holds an MBA from Temple University and a post-graduate certificate in pharmaceutical and healthcare business from the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia. Ken can be reached at kkeefer@keeferconsulting.com.