Free-From-Harm Training: Protecting Patients & Creating Competencies In Clinical Trials

By Beth Harper and David Hadden

Raise your hand if you:

- Like the way you teach or were taught about good clinical practices (GCPs)

![]()

- Believe your training approach is effective

- Feel confident that you and you and your team fully understand the complexities of your protocol.

Chances are you’re in the minority if your hand shot up. This is not only astonishing (given the importance of ensuring everyone involved in the clinical trial process is competent) but also embarrassing (given that it’s 2020 and we are still using old-fashioned methods to teach clinical research professionals how to conduct clinical trials).

The basics of medical practice are to do no harm, and the core tenets of GCPs are to protect the rights, safety, and well-being of the trial subjects. When training doesn’t allow for practicing clinical research competencies in a safe simulated environment, then we are in danger of violating the principles we are trying to teach.

Protocols are also becoming much more complex. Researchers today not only need to be proficient on the clinical aspects of complicated protocols but also need to essentially become technologists overnight. Connected devices, study management platforms, electronic consent; to steal a phrase from Gen Z — it’s a lot.

One could also argue that current approaches to training not only risk harming the research subjects, but also jeopardizing the experience of the learner, setting them up for failure, poor performance, and high turnover rates — not to mention the increased risk of costly protocol deviations. The way to stop this madness is through adoption of a free-from-harm training mentality and the use of modern teaching methods.

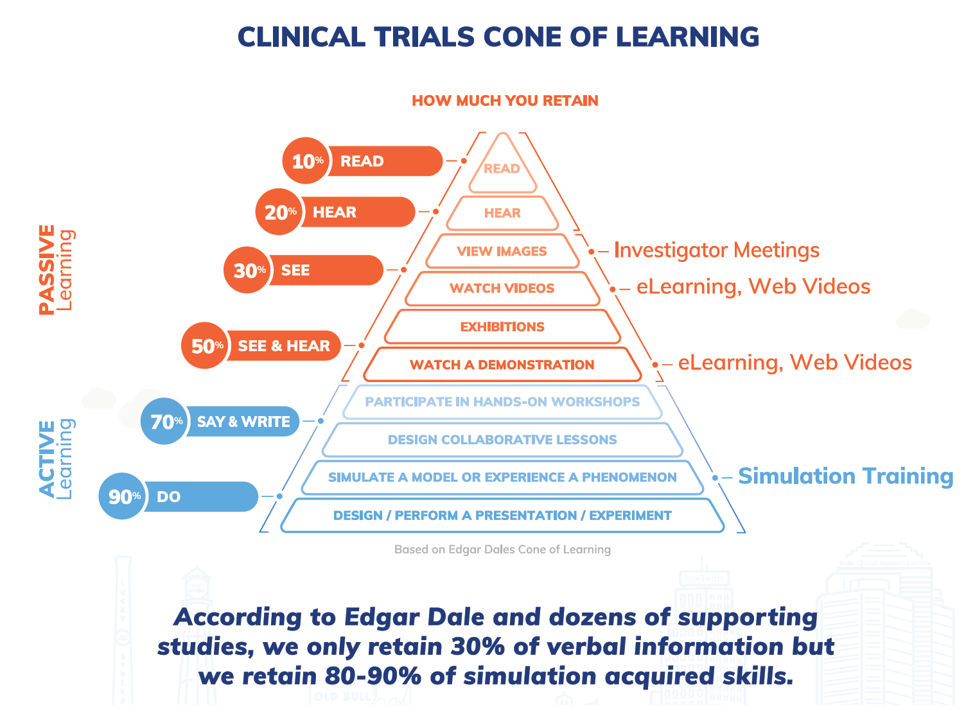

Many of the basics about competency, simulation, and better training have been addressed in prior articles,1,2,3 so we won’t repeat them here, but it’s worth pausing to briefly mention what we know about learning. Edgar Dale’s cone of experience/learning pyramid, while adapted and challenged within the learning and development industry, still provides a common-sense understanding of how people learn — by doing.

Figure 1: Adaptation of Edgar Dale’s Cone of Learning (image courtesy of Pro-Ficiency)

Just because a clinical research coordinator (CRC) can describe the elements of an informed consent document doesn’t mean they know how to properly administer and document informed consent. Just because an investigator knows s/he is responsible for the oversight of a clinical trial doesn’t mean they know how to oversee their staff. Just because a clinical research associate (CRA) can explain the ICH GCP requirements for monitoring clinical trials, doesn’t mean they know how to monitor. And, just because the entire study team knows the inclusion/exclusion criteria for a protocol doesn’t mean they can properly or efficiently screen subjects for a trial. You get the picture.

Competency is the combination of knowledge, skills/abilities, and attitude. Yet most of the way we teach about GCPs and protocols is through didactic methods, focusing on the knowledge part of the equation. Self-study, live lectures, and reviewing an eLearning module all have their place. So do quizzes and knowledge exams. But in terms of actually helping someone develop the skills and abilities to do the work of clinical research, they fall woefully short. So, where does that leave us?

If you believe Edgar Dale and you think about your own learning experience, it’s clear that the best way to learn is by doing. That’s really the power of simulation training. The airline/aerospace industry does it, the military does it, the medical profession does it.5,6 They all do it because a) it works and b) there are high stakes if it’s done wrong. When you take a flight or when you have a medical procedure, you trust that the pilot and healthcare provider are competent. Would you want to be the passenger on a flight where the pilot, who had studied all the theory, was flying the plane for the first time? Of course not. So why should we expect our subjects to participate in a clinical trial where the site staff have taken endless hours of eLearning, attended investigator meetings, or sat through the “death by PowerPoint” marches of a traditional site initiation visit without ever having actually practiced the protocol? We shouldn’t — plain and simple!

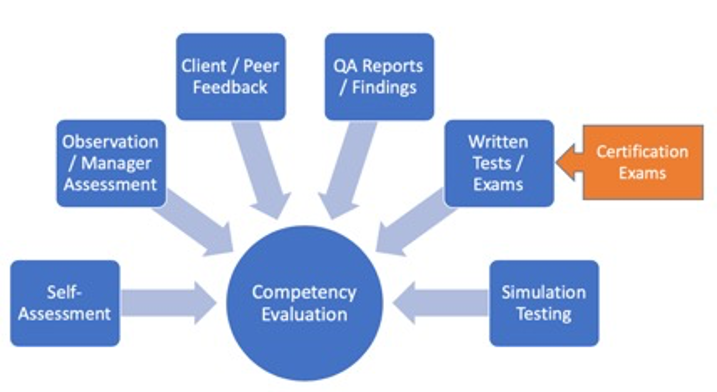

Simulation addresses another problem, which is how to actually assess competency. While there are many methods for doing so, most are applied after the fact and don’t lend themselves to just-in-time methods that allow for mid-course corrections before a serious mistake is made.

Figure 2: Competency assessment methods (image courtesy of ACRP)

Case in point: A new CRC has completed their basic GCP training. They have read the Belmont Report, Declaration of Helsinki, and ICH GCP guidelines. They have passed the quizzes within the eLearning system and they have proven they understand the essentials of the informed consent process. Yet, they have never actually practiced conducting and documenting informed consent. While the CRA may be able to identify flaws in the way the process was done several months later, it’s too late. If consent is not conducted properly, the subject will have been exposed to unnecessary risk and the data will be lost.

Certainly, the investigator and CRC’s manager could conduct various practice sessions in live clinic settings and observe how the CRC performs. But this approach is costly, time consuming, inconsistent, and highly biased by the observer. If an inexperienced and unconfident CRC is actually participating in the consenting of a real subject, what’s the likelihood that the subject will agree to participate? But what if the CRC works through several real-life scenarios in a computer-simulated clinic setting? As they go through the consenting and documentation process, they are given choices and options of what to do next. If they make a misstep along the way, they are given the chance to correct their mistake and try again. Proper learning takes place in a safe environment and is reinforced without ever exposing a real subject to the potential harm. The learner and their manager/mentor can evaluate where they have gaps, address these, and continue through the simulations until they perfect their competencies and are ready for real-life consenting. Now apply this same approach to an extremely complicated dosing schedule in a Phase 3 study. If you could predict behavior-based deviations and mitigate those risks prior to a single patient being screened, would you sleep better at night? The answer for many sponsors and sites is a resounding yes.

Simulation and competency-based training lends itself to higher cognitive skills, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills that are essential for clinical research professionals but that can’t be developed through traditional methods.

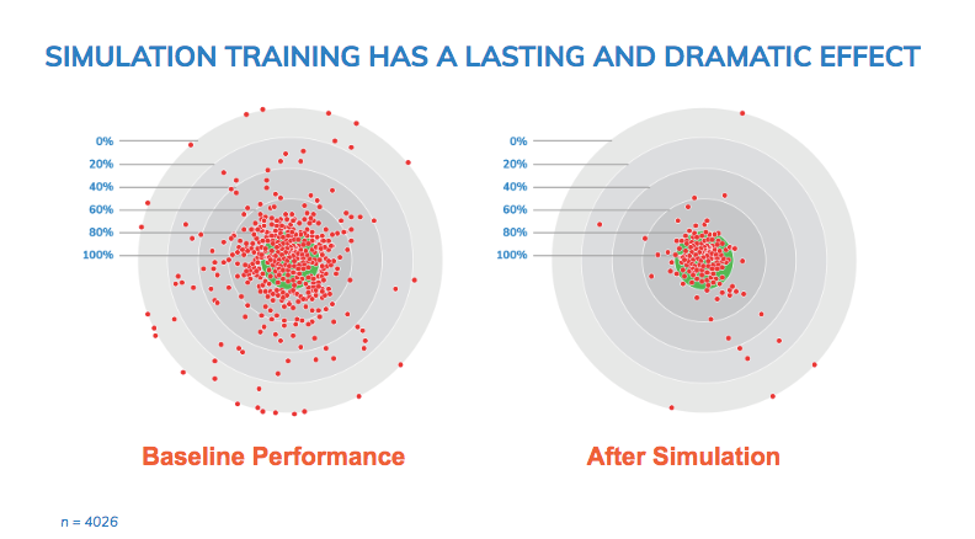

Does it actually work? Common sense tells you that it must work if all the high-risk professions mentioned above rely on it. But what about in the context of a clinical trial?

Figure 3: Impact of simulation training on protocol errors (image courtesy of Pro-Ficiency)

Figure 3 shows the frequency and severity of protocol deviations and iatrogenic errors that occurred in a study of 150 clinicians and 60 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) supported hospital sites in East Africa. Each red dot represents a simulation of a study subject going through a clinical trial. The left graph shows many severe deviations. The green target area represents the range of acceptable performance. The further from the center, the more severe the issue. The right graph shows the performance after seven to 11 hours of computer-based simulation training. The majority of clinicians improved their performance substantially.

So, what’s the barrier to adoption? It really boils down to mind-sets and money. As an industry, we are often challenged with getting out of our own way. Getting away from the “this is the way we’ve always done it” mind-set takes courage and leadership. Sure, planning for simulation training takes an investment of time and resources, but compared to the cost of making mistakes in a study, it is pennies on the dollar. Very simply, we must stop thinking about training as a “check the box” exercise and begin to recognize training and human performance management as a critical risk management strategy.

At ACRP, we are investing in developing simulation and competency-based training for clinical research professionals. We believe it’s essential to shift to more modern methods of competency development and assessment. We also believe that while the case for action is compelling, the case against not acting is even stronger.

REFERENCES

- Harper, B. Competencies And Credentialing And Certification…Oh, My!. https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/competencies-and-credentialing-and-certification-oh-my-0001

- Harper, B. Training as a Site Engagement Strategy. https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/training-as-a-site-engagement-strategy-0001

- Harper, B. A Simulation-Based Approach To CRO Selection. https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/a-simulation-based-approach-to-cro-selection-0001

- About Edgar Dale. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Dale

- Society for Simulation in Healthcare: https://www.ssih.org/

- Clinical Simulation in Nursing: https://www.journals.elsevier.com/clinical-simulation-in-nursing/

About The Authors:

Beth Harper is the president of Clinical Performance Partners, Inc., a clinical research consulting firm specializing in enrollment and site performance management. She also is the workforce innovation officer for the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP). Harper has passionately pursued solutions for optimizing clinical trials and educating clinical research professionals for over three decades. She is an adjunct assistant professor at George Washington University who has published and presented extensively in the areas of protocol optimization, study feasibility, site selection, patient recruitment, and sponsor-site relationship management. Harper serves on the CISCRP Advisory Board and the Clinical Leader Editorial Advisory Board. She can be reached at 817-946-4728, bharper@clinicalperformancepartners.com, or bharper@acrpnet.org.

Beth Harper is the president of Clinical Performance Partners, Inc., a clinical research consulting firm specializing in enrollment and site performance management. She also is the workforce innovation officer for the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP). Harper has passionately pursued solutions for optimizing clinical trials and educating clinical research professionals for over three decades. She is an adjunct assistant professor at George Washington University who has published and presented extensively in the areas of protocol optimization, study feasibility, site selection, patient recruitment, and sponsor-site relationship management. Harper serves on the CISCRP Advisory Board and the Clinical Leader Editorial Advisory Board. She can be reached at 817-946-4728, bharper@clinicalperformancepartners.com, or bharper@acrpnet.org.

David Hadden is co-CEO and chief game changer at Pro-ficiency. His career has been driven by using technology to drive change and efficiency. In 2001, he worked with Dave Barry, Father of AZT, to develop a novel simulation technology to support investigators and reduce errors in clinical trials. Since then, he has used simulation to support clinicians and investigators in 180 countries and for all major sponsors. Hadden has published six clinical studies on the impact of computerized simulation systems for the quantification of clinician behavior and reduction of medical errors and has conducted seminars and workshops in more than 40 countries. He can be reached at 919-904-0035 or at dave@pro-ficiency.com.

David Hadden is co-CEO and chief game changer at Pro-ficiency. His career has been driven by using technology to drive change and efficiency. In 2001, he worked with Dave Barry, Father of AZT, to develop a novel simulation technology to support investigators and reduce errors in clinical trials. Since then, he has used simulation to support clinicians and investigators in 180 countries and for all major sponsors. Hadden has published six clinical studies on the impact of computerized simulation systems for the quantification of clinician behavior and reduction of medical errors and has conducted seminars and workshops in more than 40 countries. He can be reached at 919-904-0035 or at dave@pro-ficiency.com.