How Africa Can Help Reverse Underrepresentation In Clinical Trials

By Tina Barton, BSc, Ph.D., MBA, COO, eMQT Ltd.

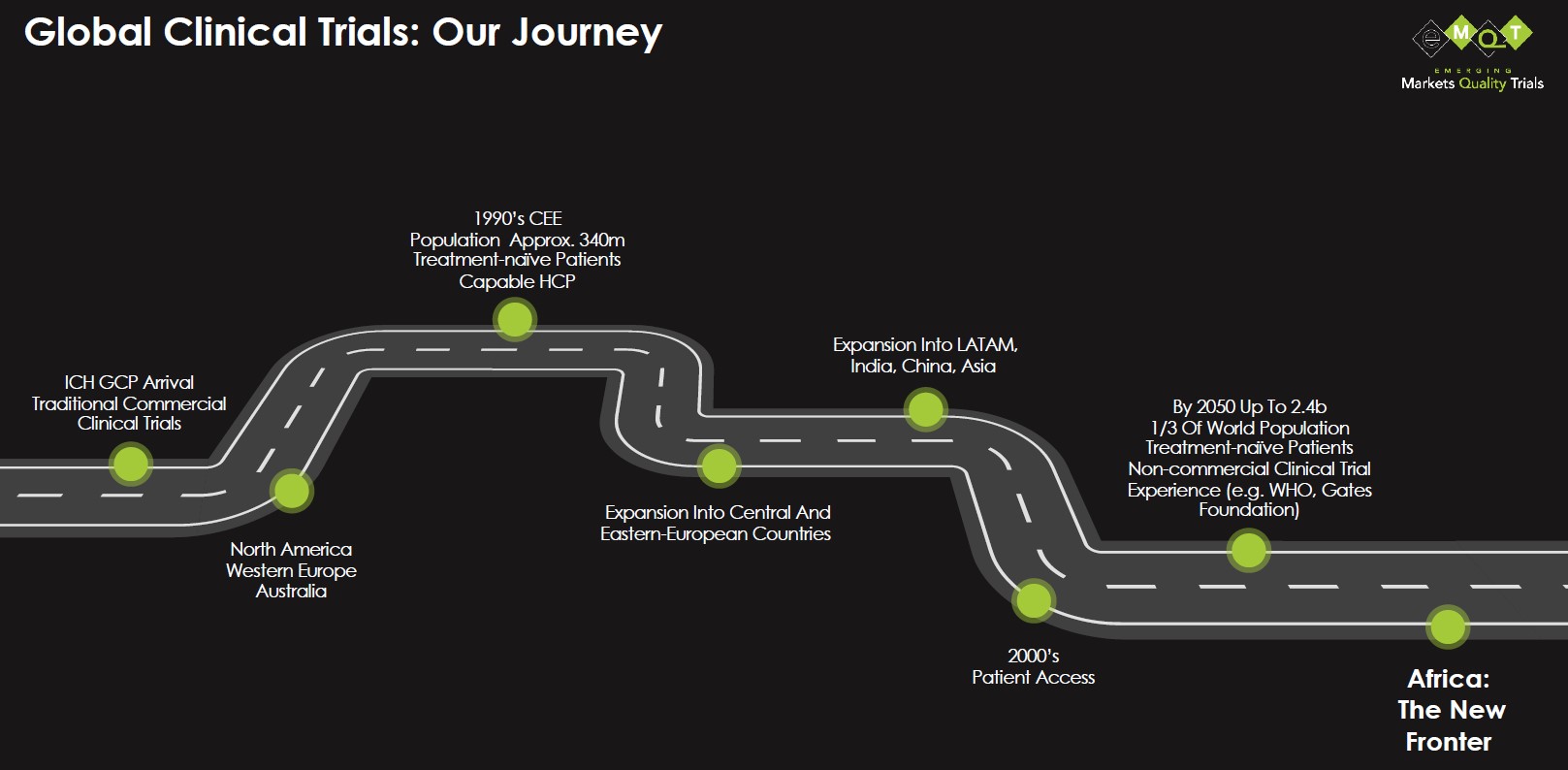

As drug development has progressed over the last 30 years, industry has looked farther beyond its own respective geographical boundaries to meet the needs of clinical trials. Initially, clinical research carried out according to GCP focused on the western world. In the early 1990s, as trials required more and more patients, together with increased speed of delivery, we started to look farther afield, initially to Central and Eastern Europe, then throughout Asia and Latin America. However, one of the largest continents in the world with a population expected to reach 2 billion by 2050 is not routinely included in our clinical trial plans. Could Africa be our “new frontier”?

Source: eMQT

It Begins And Ends With Patients

Those who have worked in clinical research for many years will know that one of the hardest activities is finding the right sites in the right countries to deliver the right patients. In addition, there are many things we need to consider when planning each and every clinical trial.

Consideration is given to medical need for patients and where these patients exist. Which countries have the necessary prevalence and numbers of patients? Do the patients have to be treatment naïve? Are the countries of choice driven by a commercial component? Meaning, is the focus on finding the company’s future markets, or is it about finding the right patients? The most important aspect in the planning of every trial is selecting the sites that can deliver the quality data needed to move a potential new medicine along its journey to a marketing license. But it almost always comes down to where we can get the patients to meet the timeline and the expected recruitment will be met.

It truly is all about the patients.

Greater Diversity Requires Greater Awareness

In the last couple of years, it has become more important, and now mandated, that our trials demonstrate diversity and inclusion to meet the needs of the disease or condition under investigation. In the U.S., 13% of the population is Black, yet only 5% are represented in clinical trials.1 Historical knowledge indicates a similar disparity exists globally for African representation in clinical trials. Now we must change this! We must proactively look at how to achieve this.

Some companies are focused on greater support for Black investigators and their Black patients in traditional countries. That will likely yield an uptick but probably a quite small one in the first instance. Consider, too, that about 11% of the sites we use will never recruit a single patient2 and, for those that do, it is usually slower than planned. What’s more, greater than 80% of trials are delayed or closed early due to recruitment issues3. We must therefore look elsewhere to find enough of the sites we need with the right patients to meet recruitment goals. So where can we make the biggest impact?

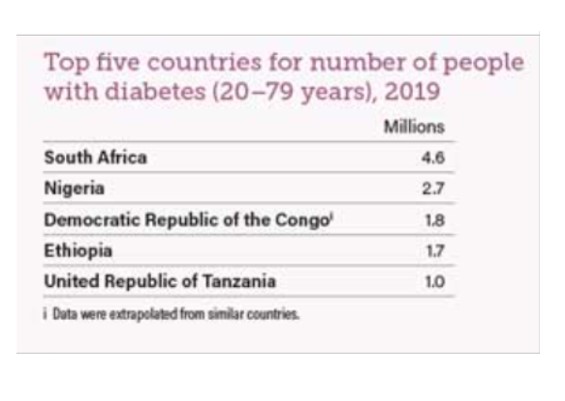

Start by including clinical trial sites from sub-Saharan Africa as routine. Africa is a continent of 54 countries, and the bulk of the continent’s population lies in sub-Saharan Africa such as Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Congo, and Uganda. Nigeria has twice the population of the next largest country and accounts for more than 16% of the continent’s total population4. In terms of engaging Africa, one could argue that South Africa is sometimes included in global trials, but this is likely because of its historical connections with Europe rather than any other reason. Additionally, and more recently, countries in the Middle East-North Africa (MENA) region have been considered.

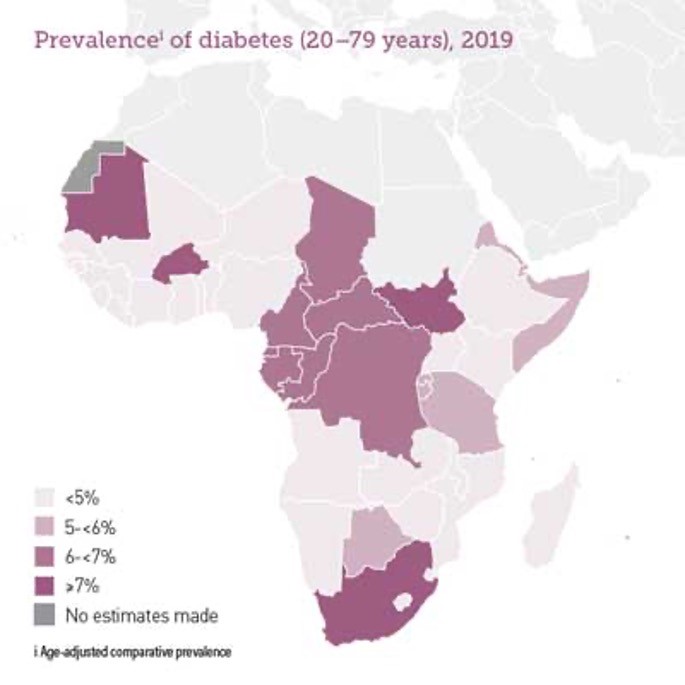

Africa has the patients, but do they have the diseases we are interested in? Africa has a high incidence of many communicable diseases, but a key focus of our industry currently is focused on non-communicable diseases with unmet medical needs such as cancers, neurological conditions, and diabetes. And on the face of it, when you compare prevalence of these in African countries to our current sources, there is a considerably smaller percentage of patients. But look again. For example, diabetes incidence in Nigeria was 2.7% in 20195. That appears very low, but of the country’s total population, that’s almost 5 million people5! Compare that to Germany, the country with the highest level of diabetes in Europe at over 15%, which equates to 9.9 million sufferers6. Or even the U.K. with almost 6% of the population, or 4.8 million people7. Yes, African countries do have the diseases of interest, and I would say the unmet medical need is greater as well.

Consider the following:

- 19 million adults (20-79) are living with diabetes in the IDF Africa Region in 2019. This figure is estimated to increase to 47 million by 2045.

- 45 million adults (20-79) in the IDF Africa Region have Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT) which places them at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes. This figures is estimated to reach 110 million by 2045.

- The IDF Africa Region has the highest percentage of undiagnosed people of all IDF regions — 60% of adults living with diabetes do not know they have it.

- 1 in 9 live births in the IDF Africa Region are affected by hyperglycaemia in pregnancy.

Fear Is Holding Us Back

So why is it that we have been slow to look to these countries when planning clinical trials? I think it comes down to one thing, and that’s fear. Fear of the unknown, fear that it won’t be safe, fear that the drugs will go missing, and fear that the doctors won’t be well trained or know how to carry out clinical trials according to global standards. But most of all, it’s our fear of speaking out and our managers declining to support this “crazy” idea. All of these are valid concerns, but they are no different from the concerns we had in the early 1990s when we looked at Central and Eastern Europe. Management asked all those same questions when I suggested looking at countries like Hungary, Slovakia, and Latvia. And what did we do then? We went and looked for ourselves, prepared with a long list of questions and returning with many answers that gave us assurances and evidence that we could do trials in these countries.

On joining eMQT and being asked to help drive the inclusion of African sites in clinical trials, I mentally got out that old list from 1990 and unearthed those same questions that would stand me in good stead. What were those questions, and what did I need to do?

- First, evaluate the knowledge, experience, and expertise of the healthcare professionals that I needed to work with – both therapeutic area and ICH GCP or other relevant regulations.

- Assess the facility infrastructure. Do they have all the necessary services, tools, equipment, and support to ensure all aspects of our trial could be delivered?

- Does the doctor who wishes to be an investigator have a team of qualified, suitable staff on the team? This would include a pharmacist, lab support, nursing support, and other services, e.g., radiographers that may be required by the protocol.

- Is there a pharmacy on-site that can safely secure the IMP, comparator products, and other trial specific medications away from the normal dispensed products?

- What approvals are required to start a trial at the site? Are they robust enough to meet global requirements? What do you have to submit, when do you have to submit it, and how long does a response take?

What do you notice about this list? It's no different from any other list you might prepare ahead of a site evaluation process, regardless of location. However, there is one big issue I haven't yet mentioned — culture. Culture is something you have to address wherever you go, but culture is particularly important to the Africans, and your first impression is critical. There are perceptions among some Africans that make them extremely nervous about working with pharmaceutical companies from the western world. Be prepared to work in a way that meets their cultural needs from the very first interaction; ensure there is face-to-face engagement at the earliest opportunity, as that is particularly important to them.

Hope Is In The Here & Now

With all that said, is it really possible to be truly diverse and inclusive with all these challenges ahead? From my experience over the last four years, I would say yes. It is not only possible, but it’s an exciting and uplifting journey. I have been to many sites across sub-Saharan Africa, spoken to many of the healthcare professionals who work there, and discovered a lot of our perceptions are unfounded. Of course, there are many things that don't look or feel like we have come to expect in our established sites. But there is one thing I have found everywhere in Africa, and that is a real desire to be included and a real willingness to dedicate time and resources to be a part of our global teams.

I found on my travels that the doctors I met may not have been involved in clinical trials for pharmaceutical-led drug development within their own country but many trained, worked, and/or continue to return to countries already established in clinical trials, like the U.S., U.K., Germany, and France. They are genuinely keen on research and often perform their own local research programs with colleagues around Africa. One thing I learned very quickly was that staff resources are not limited, and many more people are just waiting for a new role. With teams in place, the next question was, are they trained? Yes, but ICH GCP is not well known, and so training is almost always required. Still, that is not unusual anywhere, as many clinicians, new and old, need training or refreshers.

Hospital infrastructure is very mixed, but almost all hospitals I visited had excellent facilities to enable the clinical research activities to occur successfully. These include up-to-date laboratory equipment, skilled technicians, and the willingness to invest time and effort into something that was lacking.

Visiting the clinics across Africa with eMQT. Source: eMQT.

Let me give you an example: One particular site did not have a separate lockable storage area outside of the general pharmacy for the IMP, so they took an underused room and converted it into a lockable pharmacy storage area.

Another area we have to assess is whether the regulatory and ethical approval systems in each country, and their oversight through the course of the study, meet global requirements to assure we have validated data at the end of the trial. We did discover that many of the ethics committees may not have the processes documented in the way that we require, but they are very stringent in terms of assessing any protocol. We discovered that letting us folks outside of Africa get our hands on their data is of great concern. What will we do with it? This is primarily because of historical cases where the Black patients’ data has not been properly accounted for and/or was used without appropriate consent. So, together we will learn what assurances they need from us — they have a material transfer agreement process that is required for all import and export of data and samples including drugs — as well as the support they need from us — training in the nuances of commercial clinical trials for drug development around safety reporting, drug management, documentation, and consent, to name just a few. None of these are insurmountable, as we overcome them all the time with our established sites. We must now include African sites where it is applicable for the protocol under consideration from a perspective of the disease area, available patients, and interest in the drug under investigation.

The Benefits Of Including Africa — For All

Throughout my long career in clinical research, the main challenge for any protocol is patient recruitment. Are we getting the patients into the study quick enough? Do we have enough patients, and are they spread across the geographies to represent the global distribution of patients with this illness? Constant evaluation and re-evaluation are needed through start-up. Africa truly presents an opportunity to achieve many things:

- A new source of patients, many of whom are likely drug naïve

- Better global distribution of patients, which can help move the needle from 3% Black patients

- Keen and enthusiastic investigators with no bad habits from prior studies

- Opportunity to bring greater investment into the country for healthcare, with additional staff needs and adding infrastructure for clinical trials

- Greater assurance to meet our recruitment goals

- Timed saved without the need for rescue interventions when goals have not been met.

- Earlier decision points that have the potential to shorten the drug development pathway

And for me, most importantly, Africa presents the opportunity for patients to get access to previously unattainable medicines and better medical care while supporting the growth of new medicines.

So, how many African sites will you plan for in your next and then, truly global trial?

References:

- Increasing Diversity in Clinical Trials: Overcoming Critical Barriers. Luther T. et al. Current Problems in Cardiology 2019;44:148172.

- Recruitment and retention of the participants in clinical trials: Challenges and solutions. Nayan Chaudhari, Renju Ravi, Nithya J. Gogtay, and Urmila M. Thatte. Perspect Clin Res. 2020 Apr-Jun; 11(2): 64–69. Published online 2020 May 6. doi: 10.4103/picr.PICR_206_19

- Recruitment and retention of participants in clinical studies: Critical issues and challenges. Mira Desai. Perspect Clin Res. 2020 Apr-Jun; 11(2): 51–53. Published online 2020 May 6. doi: 10.4103/picr.PICR_6_20

- African Countries by population (2023). Worldometer. African Countries by Population (2023) - Worldometer (worldometers.info)

- Diabetes prevalence (% of populations ages 20 to 79) – Sub-Saharan Africa. International Diabetes Federation, Diabetes Atlas. The World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.DIAB.ZS?locations=ZG&view=map

- Prevalence of diabetes in adult population in Europe 2019, by country. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1081006/prevalence-of-diabetes-in-europe/

- Diabetes Prevalence 2019. Diabetes UK. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/professionals/position-statements-reports/statistics/diabetes-prevalence-2019

About The Author:

Tina Barton, Ph.D., COO of eMQT, is a drug development specialist with over 40 years’ experience, working in partnership to lead for success as a customer-focused senior leader. Barton provides strategic business acumen, change management, and process enhancement expertise with a proven track record in driving growth, managing teams, and training for the future, from large global organisations to small startup enterprises. With a passion for transformation, Barton drove the embracement of Central Eastern European countries and now is focused on the inclusion of sub-Saharan Africa in clinical development — bringing the miracle of medicines to emerging markets and new patients. Barton holds a BSc, Ph.D., and MBA alongside over 50 academic publications and is an honorary fellow and board member of the Institute of Clinical Research.