How Including Patient Voices in Clinical Trial Design Can Deliver Many Benefits

Enrollment is key to any clinical trial — but it is absolutely critical for rare disease studies. Patients, as much as the site, ultimately determine whether a trial is successful. Listening to patients and their caregivers could help speed the way to cures for these devastating conditions.

A case for a cure

When a son is born, most parents have high aspirations. They dream that he will become an athlete, a doctor, a leader — and that he will carry on the family name. Melissa and Chris Hogan have high hopes for their son Case, too. They dream that he will survive and enjoy quality of life.

“Case was born in 2007 — a robust, 10-pound, 1-ounce baby boy. After several hours, he was diagnosed with a dangerous lung condition,” says Melissa Hogan. After several days on a ventilator in neonatal intensive care, he recovered. “He continued to grow and laugh, but was always plagued with colds and ear infections, choking episodes, loud breathing, interrupted sleep and, after he started walking, pigeon toes.”

Those seemingly unrelated symptoms ended up being connected. In 2009, 2-year-old Case was diagnosed with MPS II, a mucopolysaccharide storage disease known as Hunter syndrome after Charles Hunter, who first described it in 1917. Individuals with Hunter syndrome have a deficiency of the enzyme iduronate sulfatase, which is necessary to break down long sugar molecules known as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), previously called mucopolysaccharides. As a result, certain GAGs called dermatan sulfate and heperan sulfate accumulate in the body, causing progressive damage that leads to a wide spectrum of physical and mental problems.

The condition occurs along a continuum from severe to attenuated and affects each child differently. Children with Hunter syndrome may have numerous seemingly minor health problems — runny nose, chronic ear and sinus infections, frequent coughs and colds. That’s what made Case’s grandmother, a nurse, suspicious when she saw the condition on an episode of Mystery Diagnosis.

Breathing problems are common, as the disease affects the lungs and airways. Buildup of GAGs can cause the heart valves to thicken, decreasing cardiac function. The liver and spleen usually become enlarged, which can cause further problems with breathing or eating. GAGs can build up in the retina, causing loss of peripheral vision and night blindness, and some degree of deafness is also common. The disease can affect the joints, causing stiffness and eventually making it difficult to pick up small objects or even to walk normally. It can also affect the bones, limiting growth.

In about two-thirds of patients, Hunter syndrome also affects the brain and nervous system. Cognitive development usually slows between the ages of 2 and 5, and regresses after that. Behavioral issues similar to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, obsessive/compulsive disorder (OCD) and sensory processing disorder are also common, and some children are a danger to themselves. Life expectancy is limited.

Hunter syndrome at a glance

- What it is: A genetic mucopolysaccharide storage disease, MPS II, one of several lysosomal storage diseases.

- How it’s acquired: Like hemophilia, MPS II is X-linked recessive. The iduronate-2 sulfatase gene may mutate spontaneously, or the birth mother may be a carrier.

- Who it affects: Hunter syndrome affects between 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 150,000 live male births. Today it affects about 2,000 boys and men worldwide.

Sources: The National MPS Society, SavingCase.com

A family tries to cope

In 2009, Melissa Hogan had her own small legal and consulting practice and was raising three children with her husband, Chris. “It was busy, fun and crazy — normal,” she says. “Once Case was diagnosed, it literally started this tidal wave of change.”

Case started seeing 10 different medical specialists. He was evaluated every six months, which often required spending an entire day at the hospital. He also spent every Thursday at the hospital receiving weekly enzyme replacement therapy infusions. In addition to dealing with Case’s medical needs, the family had to address many other issues, ranging from insurance coverage to accommodations at school.

“Initially I was still trying to balance work, but over time that all receded as a result of practicality,” Hogan says.

The enzyme replacement therapy that Case was receiving, and will need to receive for the rest of his life, helps break down the cellular waste that builds in his body. However, the enzyme molecule is too large to cross the blood/brain barrier, so it does not address the cognitive decline. Soon after Case’s diagnosis, the Hogans learned of a Phase I/II clinical trial to gather safety data on a treatment designed to reach the brain.

“They reformulate the enzyme so it’s more concentrated and modify the pH to be appropriate in spinal fluid instead of blood,” Hogan says. The enzyme is injected through an intrathecal, or spinal, port or via lumbar puncture into the cerebrospinal fluid, which carries it to the brain. “The trial was on our radar from the very beginning. Three months after Case was diagnosed, we took him to see a leading specialist to learn more about the trial and about the disease in general. We were clear: ‘We’re on board with the trial as soon as it starts.’”

The trial started enrolling several months later, and that’s when the Hogans began to hit roadblocks. Patients had to be at least 3 years old, and Case was only 2 when he was diagnosed. Just before he turned 3, he was screened, but he was deemed too high functioning to participate in the trial, which sought patients with clear cognitive impairment. Investigators were looking for patients with IQs of 55 to 75.

“An average IQ is 100. Just before Case turned 3, his IQ was 88, but we knew he was cognitively impaired. It was frustrating not to qualify at the time,” Hogan. “Over the next eight months we watched him lose some speech, and he got worse and worse behaviorally. We had a certified nursing assistant five days a week and baby gates between all our rooms. Eventually, to go in public, we often had to have him in a wheelchair with a six-point harness because he had no sense of safety.”

Within that time, Case’s IQ dropped 18 points and he then qualified for the trial. Soon thereafter, the sponsor would broaden the IQ criteria because the original criteria excluded too many participants.

The clinical trial experience

When Case first entered the clinical trial, “All we wanted to do was save his life. We hoped to stabilize his brain and keep him alive and stable long enough for something better to come along,” Hogan says. “We had a friend whose son was the first child in the trial. We had seen what it was doing for him, so I knew what the potential was.”

Clinical considerations: Participating in a clinical trial is not without risks. It’s important to understand how the target demographic perceives the risks associated with a given trial and how those risks affect the decision whether to enroll.

The Hunter syndrome trial required implantation of an intrathecal device — a port to deliver the enzyme into the cerebrospinal fluid. One major concern was that the device would break internally.

“We always tempered the risk against the risk of the disease. We knew Case could die somehow in connection with an experimental trial, but at least we’ll do that fighting. We knew the prognosis was not good,” Hogan says. Case participated in the six-month Phase I/II trial and then in the long-term extension. He has been on the drug since January 2011.

Device breakage did threaten the trial. At one point, the hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB) put the trial on hold and would not enroll any more patients. Hogan wrote to the IRB explaining that problems with the port posed less of a risk than the disease itself. Although the IRB lifted the hold, ultimately, the sponsor selected a new device.

Logistical roadblocks: “Many of the challenges to participation have nothing to do with whether the families think the drug has potential,” Hogan says. “It’s about, ‘How are they going to make it work in their family and their life?’”

For example, for the first seven months after Case was enrolled, the Hogans had to be at the hospital in North Carolina for nine days every four weeks. Although they were able to make it work with lots of help from family, the lengthy stays could be particularly difficult for a single parent, for example. “These very long visits prevent a lot of people from enrolling,” Hogan says.

Money can also be an issue. “In four years, we went through $14,000 that we had set aside in a separate account,” Hogan says. “Some families didn’t know that the pharmaceutical company would pay for the flight, hotel, car and a daily stipend that started off very small.” Advocates suggest that families hold fundraisers for help with costs that the trial sponsor doesn’t cover.

Design barriers: Trial design itself can create challenges. It’s important that the enrollment criteria aren’t so narrow that they result is a study sample that is too small or only includes a part of the population that does not represent the whole. Case would have been enrolled much earlier if the original criteria regarding cognitive ability had not been so narrowly defined.

Another issue arose in the intrathecal infusion trial. The main endpoint was cognitive results — which were challenging to measure in participants in Hunter syndrome patients, because they are easily distracted.

“We knew there were variables among sites,” Hogan says. “One tester couldn’t handle the behaviors very well. Another site had a tester who was experienced handling the behaviors, but it was a more distracting environment.”

|

Study Subject Insights |

|||

|

|

On first learning about study |

While in trial |

After trial/Compassionate use |

|

Hopes, Fears, Expectations |

|

|

|

|

Information Sources |

|

|

|

TABLE I: Shown here is an example of qualitative research eliciting the kinds of feelings that patients and caregivers might have at different points along their clinical trial journey — and where they go for answers. This type of feedback can offer sponsors and sites valuable insight into issues affecting the trial.

Creating a 360-degree feedback loop

Hogan praises the investigative team at the hospital. “They knew the disease. They knew the kids,” she says. “They were very flexible. They would listen to feedback and give us feedback as well.”

Still, she said, she saw that the trial could have been more effective and efficient, that patients could have been enrolled faster. In addition to her blog and the website SavingCase.com, Hogan has launched the “Ask 100 Patients” initiative to enhance communication with study sponsors and investigators.

“Patients and their caregivers can give you a broad base of knowledge about the disease, the course of the disease and patient preferences,” she says, because they live with things the physicians don’t see often. “Even within our community, particular people are experts on certain topics. Some parents are the hydrocephalus experts. In our parent community, I’ve become the expert on intrathecal delivery systems. Next month, Case will have his sixth surgery for the delivery system.”

With patient input, “you can design a better trial while meeting regulatory requirements,” says Ross Weaver, PharmD, MBA, managing director of Clinical SCORE.

To that end, some pharmaceutical companies are adding patients to their advisory boards or having them participate in trial design. At least one has added a patient advocate, who reports to the vice president of research and development. “That’s a start, but it’s limited,” Weaver says. “An N of 1 cannot answer all your questions. A broader perspective is necessary — and getting that insight requires listening to the voices of many patients who participated in the company’s clinical trials.”

The Food and Drug Administration is reaching out to groups of patients with certain conditions as a way to better understand the patient experience and what to consider for a clinical trial. “That’s a very good idea and can be helpful — but companies may have different needs or aspects they need to think through. They may have different endpoints or a slower onset,” Weaver says. The FDA initiatives may establish a foundation, “but you still have to figure out what you need for your compound.”

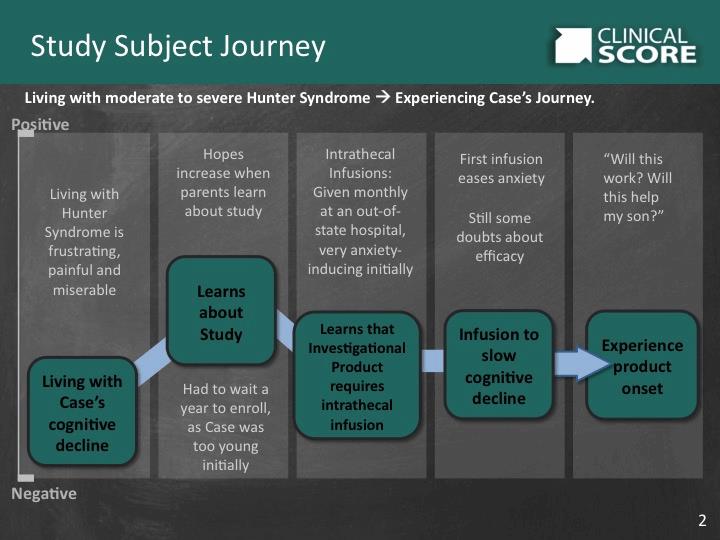

TABLE II: It is important to understand patients’ positive and negative experiences in order to address barriers to successful trial participation.

Clinical trial insights are critical

Many of the roadblocks that clinical trials face, such as enrollment and compliance, can be addressed successfully if sponsors and sites learn to see the world from their patients’ perspective. Some organizations are taking steps in that direction, but they don’t go far enough. Without hearing from a number of trial participants, sponsors miss out on a substantial knowledge base.

Systematically interviewing participants at the end of a Phase I and/or Phase II trial provides the first-hand perspectives that are essential to positioning Phase III trials for success. Similarly, interviewing members of the targeted patient demographic provides the information necessary to eliminate barriers to enrollment that may be stalling a Phase II study. And that’s just the beginning. Clinical SCORE’s CTI™ process is designed to elicit patients’ hopes, fears and expectations and to provide the deep insight into their experience with your trials so you can reach your goals.

A patient-centered approach makes sense. To get a deeper understanding of patient experience with your trials, contact Ross Weaver at (877) 334-0100 or email Ross.Weaver@clinical-score.com.

The benefits of learning to listen

A patient-centric approach that includes patient and caregiver input can provide such insights as:

- The vocabulary patients use to obtain information about their disease and treatments

- Patient and caregiver experiences during the trial

- Additional benefits of the compound or device

- Accuracy of brand positioning

- The relevance and potential management of specific adverse events

- Ways to optimize patient support programs