How Psychological And Cultural Safety Can Accelerate Diverse Patient Recruitment And Retention

By Valerie Schaeffer, consultant, The DOT Connector, LLC

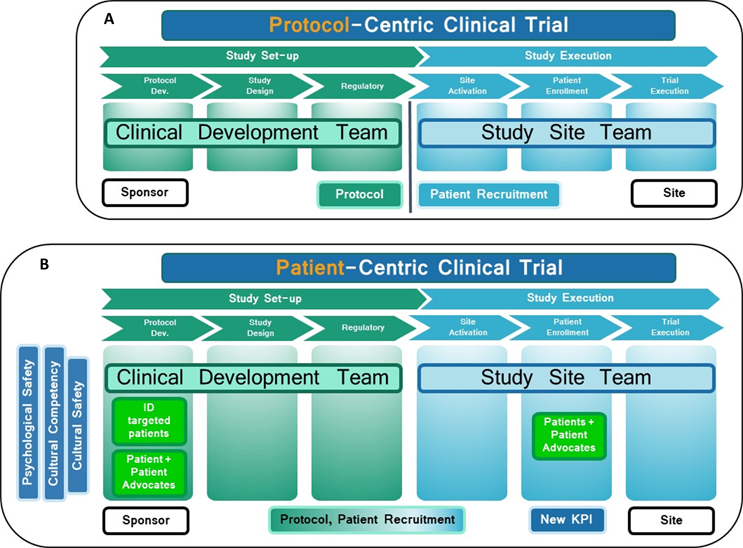

By now, many of us working in clinical trials understand the ongoing issues of representation, retention, and delays in clinical trial recruitment. What may not be as easily understood is that the reason for these challenges lies in protocol-centric trial design. Traditionally, the sponsor's clinical development team hands over a protocol and study documents to study sites and investigators, and patient recruitment starts at the site level (Fig. 1A). However, the recruitment plan's strict inclusion/exclusion criteria, English-only informed consent forms and documents, and measly reimbursement options, among other things, exclude many patient populations from participating, leading to delays and unequal representation. One way to resolve that issue is with a patient-centric trial design created on a foundation of psychological and cultural safety.

In Recruitment And For Retention, Representation Matters

About 80% of clinical trials are delayed due to patient recruitment and retention problems, often for more than a month, which costs sponsors between $600,000 and $8 million daily.1 Recruitment strategies must be inclusive and focus on patient experience to ensure retention, as replacing a patient is more than three times the cost of enrolling a patient2 and is sure to delay the study.

Representation in clinical trials is a moral, scientific, and medical issue.3, 4 For clinical trial results to be meaningful, sponsors need to enroll a sample population representative of the real-world patient population for the disease.

Accelerating the representation, recruitment, and retention of diverse patients relies on sponsors, not on study sites or investigators. They are responsible for addressing the barriers preventing participation and abandoning the protocol-centric design. Sponsors must develop a patient-centric clinical trial design and address patient recruitment early in the drug development process (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1: (A): Protocol-centric approach. The protocol is given to the sites, and patient recruitment starts at the site level. (B): Patient-centric design. Patient recruitment plans are integrated into the protocol/study design. Psychologically safe and culturally competent/safe diverse clinical development and study teams cater to the diverse patient populations' needs. The barriers to participation are addressed. The shift to patient-centric clinical trial design boosts diverse patient enrollment. The new process is continuously improved through a quality improvement program and monitored through a new key performance indicator (KPI) dedicated exclusively to diverse patient experience.

By defining and identifying the targeted patient populations and involving patients and community representatives early in the process, sponsors can help the clinical development team understand the barriers to participation and retention and give patients a sense of belonging. Translating clinical trial documents into different languages or adapting them to different literacy levels and offering reimbursements for childcare and transportation would provide an inclusive patient-centric environment. A sponsor-patient partnership in the early phases would also facilitate the outreach process, improve recruitment and retention, and improve patient outcomes (Fig. 1B).

Hire Diverse Teams Helps — But Don't Stop There

Several studies indicate that patients feel more comfortable when treated by healthcare providers who match their race and/or ethnicity,5, 6 as it decreases implicit biases and increases patients' trust in the healthcare system and improves medication adherence.6 A 2021 impact report from Tufts University demonstrated a correlation between a more diverse study site personnel and increased enrollment of diverse patient populations.7 Sponsors have long been urged to hire diverse research teams, investigators, and healthcare providers to meet diverse patient populations' needs.8 Increasing the diversity of clinical development and study site groups is one of the ways to improve patient recruitment and retention.3, 9

Unfortunately, several studies,10, 11 including one published in February 2022,12 argue that diversity hurts teamwork. Two researchers studied the influence of diversity on team performance in six large pharmaceutical drug development companies.12 Drs. Bresman and Edmonson, who examined 62 teams, concluded that diversity slightly lowered the teams' performance.12 However, Bresman and Edmonson hypothesized that diversity is necessary, but insufficient alone, for breakthrough performance. They hypothesized that creating an environment where all team members feel safe to share their ideas without fear of ridicule is essential for diverse teams to achieve their potential. This concept is referred to as psychological safety. Diversity was undeniably associated with higher performance in groups with high psychological safety. Conversely, diversity was more negatively associated with performance in teams with lower psychological safety.12

Integrating Psychological Safety: What It Is And What It Isn’t

Ten years ago, Google's Project Aristotle researched the characteristics of successful teams. The common feature of successful high-performing teams was psychological safety.13 Team psychological safety (TPS) allows people to feel secure and respond adequately to organizational challenges and personal engagement. Since 1999, Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School Amy Edmondson's groundbreaking work led to many other studies.14 So, what is TPS?

Psychological safety is the belief that no one will be judged, humiliated, or punished for speaking up, asking questions, or admitting a mistake. A psychologically safe culture creates an inclusive workplace, favoring a learning environment and leading to innovations.14, 15, 16 The benefits of TPS are numerous.16 Developing psychologically safe teams increases employee engagement by 76%, productivity by 50%, the likelihood of successful innovation, and the ability to recruit and retain talent (decreases turnover by 27%), and it decreases non-compliance events.16 TPS is not a license to say anything in a meeting, nor is it a place where praise is guaranteed, low-performance standards are accepted, or a lack of accountability is allowed.

TPS is a simple, measurable concept, easy to implement but harder to achieve. It requires the buy-in of higher-ups and the willingness of the team's leadership to be vulnerable and promote respect. Active listening and accountability are skills needed to foster this inclusive workplace culture. Allowing diverse clinical development and study site teams to feel psychologically safe and become high-performing, effective groups will lead to clinical trial design more adapted to the needs of real-world patient populations.

From Cultural Competency To Cultural Safety

Although TPS allows teams to unleash their potential and collaborate effectively, another critical element to accelerate the recruitment and retention of diverse patient populations is the need to understand and respect each other's differences.17 Cultural competence involves recognizing and acknowledging unique health beliefs, disease prevalence and incidence, and treatment outcomes for different populations. These factors, whether race/ethnicity, gender, sex, faith, language, location, or socioeconomic conditions, must be considered when caring for patients, as they impact patients' outcomes. With cultural competency comes the need to minimize the impact of one's implicit biases and to be mindful of one's own unconscious biases.

In 2015, Transcelerate BioPharma urged sponsors and investigators to train their teams in cultural competency to improve the patient experience.17 They argued that teams would be better prepared to anticipate the practical needs of patients, from informed consent and other documentation to culturally appropriate communication during site visits. Culturally competent teams help improve patient engagement, enrollment, and retention.17 Although it is possible, with training, to develop the skills needed to be culturally competent and aware of one's unconscious biases, it still leaves the patient at the will of the practitioner's skill level.

Cultural Safety Gives Power To The Patient

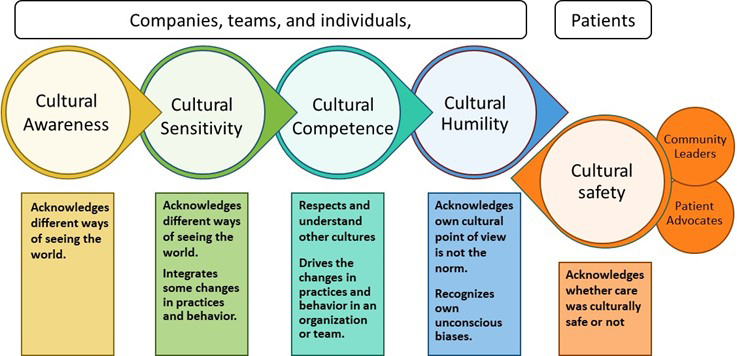

Cultural competency and cultural safety are part of a spectrum of learnings in which companies, organizations, and individuals become more open, tolerant, and respectful of cultural diversity (Fig. 2). Understanding cultural diversity and becoming a proficient intercultural caregiver is based on knowledge, skills, and attitude. Without cultural safety, the providers decide if they provide culturally acceptable care. Cultural safety is an outcome given by the patient based on the practitioner's ability (or willingness to learn), attitude, and skills (Fig.2).18

Figure 2: The cultural awareness-cultural safety spectrum: Companies, teams, and individuals start their journey at the awareness level and progress through learning, understanding, and self-reflection to cultural humility. Measuring cultural safety is the outcome and gives feedback on how well the journey progresses. Other essential factors that influence cultural safety and help providers and patients have a more harmonious partnership: the involvement of community leaders, clinical cultural brokers, and patient advocates. (Adapted from reference 18.)

Cultural safety is a concept developed in New Zealand in 1989 by Māori nurses to help address the inequity of the healthcare system for the Māori population.19 In Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, cultural safety is considered a fundamental human right and is either a legislative or policy requirement to direct the care of indigenous populations. The root of cultural safety is the recognition of colonization and the cultural losses it induced.20

Cultural safety is about recognizing the practitioner's biases, the power imbalance, and the barriers to effective clinical care. It shifts the power back to the patient and gives the patient the authority to say if the care provided was culturally safe.19 In addition, cultural safety introduces the notion of cultural humility, meaning the healthcare practitioner recognizes that their cultural values are different and does not assume they are the norm.

Although developed for indigenous populations, the cultural safety curriculum applies to any minority, including racial/ethnic groups, religious groups, transgender patients, people with disabilities, and people of different socioeconomic status or national origin.

Cultural safety is essential to achieving diversity in clinical trials.21 Measuring the efficacy of such training and practice is possible with the validation of cultural safety measurement tools,22, 23 a robust continuous quality improvement (CQI) process to improve cultural competency, and cultural safety training. Although measuring cultural competency is possible at the individual and the company level through questionnaires, it relies on self-assessment. Measuring cultural safety through a questionnaire allows the recipients to give feedback on whether the training goal was attained. It also permits the implementation of a new KPI dedicated explicitly to diverse populations, measuring the diverse patient experience. This feedback loop will help refine and improve the diverse patient experience and, eventually, accelerate the recruitment and retention of real-world patient populations.

As sponsors enable their diverse teams to unleash their creativity in a psychologically safe environment while being sensitive to the needs of others, they will design protocols, consent forms, and reimbursements adapted to the needs of real-world patient populations. The shift from protocol-centric to patient-centric clinical trial design will boost diverse patient enrollment. Implementing simple steps to create culturally competent/safe clinical development and study site teams will empower patients and patient advocates and improve diverse patient recruitment and retention, ultimately accelerating the drug’s time-to-market. Diverse patients and patient advocates will feel included and part of the mission to advance healthcare, empowered by the voice given to them during and after the clinical trial.

References:

- https://www.antidote.me/blog/what-clinical-trial-statistics-tell-us-about-the-state-of-research-today Sep 10, 2020

- https://mdgroup.com/blog/the-true-cost-of-patient-drop-outs-in-clinical-trials/ October 1, 2020

- Peters U, Turner B, Alvarez D, Murray M, Sharma A, Mohan S, Patel S. Considerations for Embedding Inclusive Research Principles in the Design and Execution of Clinical Trials. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2022 Oct 14:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s43441-022-00464-3. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36241965; PMCID: PMC9568895.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Policy and Global Affairs; Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine; Committee on Improving the Representation of Women and Underrepresented Minorities in Clinical Trials and Research; Bibbins-Domingo K, Helman A, editors. Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2022 May 17. 2, Why Diverse Representation in Clinical Research Matters and the Current State of Representation within the Clinical Research Ecosystem. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK584396/

- Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, et al. Association of Racial/Ethnic and Gender Concordance Between Patients and Physicians With Patient Experience Ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583

- https://theconversation.com/minority-patients-benefit-from-having-minority-doctors-but-thats-a-hard-match-to-make-130504

- https://medicine.tufts.edu/news-events/news/increase-diversity-clinical-trials-first-increase-staff-diversity Tufts CSDD Impact Report. New Study Finds Site Personnel Race and Ethnicity Highly Correlated with Diversity of Patients Enrolled. November/December 2021, Vol. 23 No. 6.

- Hwang T. J., M.D., and Brawley O. W., M.D. New Federal Incentives for Diversity in Clinical Trials N Engl J Med 2022; 387:1347-1349 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp2209043

- Kelsey, M. D., Patrick-Lake, B., Abdulai, R., Broedl, U. C., Brown, A., Cohn, E., Curtis, L. H., Komelasky, C., Mbagwu, M., Mensah, G. A., Mentz, R. J., Nyaku, A., Omokaro, S. O., Sewards, J., Whitlock, K., Zhang, X., & Bloomfield, G. S. (2022). Inclusion and diversity in clinical trials: Actionable steps to drive lasting change. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 116, 106740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2022.106740

- Horwitz, S. K., & Horwitz, I. B. (2007). The Effects of Team Diversity on Team Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Review of Team Demography. Journal of Management, 33(6), 987–1015. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307308587

- Williams Katherine Y. and Charles A. O'Reilly. 1998. "Demography and Diversity in Organizations: A Review of 40 Years of Research." Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews Vol. 20 (1998).

- Bresman, Henrik, and Amy C. Edmondson. "Exploring the Relationship between Team Diversity, Psychological Safety and Team Performance: Evidence from Pharmaceutical Drug Development." Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 22-055, February 2022.

- Bergmann, B., & Schaeppi, J. (2016). A data-driven approach to group creativity. Harvard Business Review, 12th July 2016.

- A.C. Edmondson Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams Administrative Science Quarterly, 44 (1999), pp. 350-383

- Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014. 1:23–43 Amy C. Edmondson and Zhike Lei Psychological Safety: The History, Renaissance, and Future of an Interpersonal Construct

- https://www.accenture.com/us-en/blogs/business-functions-blog/work-psychological-safety

- https://www.transceleratebiopharmainc.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Clinical-Trial-Diversification-Better-Practices-3-Cultural-Competency-vPresentation-1.pdf Clinical Trial Diversification Better Practices Transcelerate BioPharma Inc, Apr.-May 2015

- https://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/docs/default-source/itr/tools-and-resources/indigenous-cultural-competency-primer-e.pdf (A Journey We Walk Together)

- Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D. et al. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Int J Equity Health 18, 174 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3

- Cultural safety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people: A background paper to inform work on child safe organisations. January 2018 https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Cultural%20Safety%20background%20paper%20

January%202018_1.docx - https://www.demanddiversity.co/post/why-cultural-safety-is-an-important-step-towards-achieving-diversity-in-clinical-trials

- Elvidge E, Paradies Y, Aldrich R, Holder C. Cultural safety in hospitals: validating an empirical measurement tool to capture the Aboriginal patient experience. Aust Health Rev. 2020 Apr;44(2):205-211. doi: 10.1071/AH19227. PMID: 32213274.

- Gladman J, Ryder C, Walters LK. Measuring organisational-level Aboriginal cultural climate to tailor cultural safety strategies. Rural Remote Health. 2015 Oct-Dec;15(4):3050. Epub 2015 Oct 8. PMID: 26446197.

About The Author:

Valerie Schaeffer, Ph.D., NREMT-P, was born and raised in France, except for a preschool and kindergarten stretch in the U.S. As an adult, she returned to the U.S. to attend Rockefeller University as a Ph.D. candidate, where she encountered a unique learning experience surrounded by exceptional faculty and students and a highly psychologically safe environment. After completing her Ph.D., she moved back to Europe and Africa, before settling in Seattle, where she joined the University of Washington as a clinical researcher.

Valerie Schaeffer, Ph.D., NREMT-P, was born and raised in France, except for a preschool and kindergarten stretch in the U.S. As an adult, she returned to the U.S. to attend Rockefeller University as a Ph.D. candidate, where she encountered a unique learning experience surrounded by exceptional faculty and students and a highly psychologically safe environment. After completing her Ph.D., she moved back to Europe and Africa, before settling in Seattle, where she joined the University of Washington as a clinical researcher.

Currently, Valerie is a consultant at The DOT Connector, LLC, transforming diverse clinical development and study site teams into high-performing, effective groups with psychological and cultural safety and giving diverse patients the authority to say whether the care was culturally safe, accelerating the recruitment and retention of diverse patient populations.

She can be contacted at valschae@thedotconnectorllc.com.