How The U.S. Can Beat China In Biotech

By Brian Finrow, Lumen Bioscience

China’s emergence as a biopharma powerhouse has become a hot topic in the industry.

Observers point to growing numbers of biotech startups, a surge in drug approvals, and major licensing deals flowing westward from China. This prompts worries that America could lose its long-held lead in biopharma innovation.

Before panicking, though, it’s important to step back and examine the root cause of China’s new prominence. There’s no magic to China’s biopharma boom; rather, it is the predictable result of its well-known ability to take commoditized business activities and scale them up.

The path forward for continuing U.S. leadership becomes much clearer with the underlying drivers properly understood.

The Commodity Playbook: Scale And Cost Domination

Start with common knowledge. China has a well-honed playbook for dominating industries that entails scaling up massively to drive costs down, leveraging its low labor costs, offering state subsidies, providing regulatory support, and, above all, encouraging the cutthroat entrepreneurial vigor of its private sector.

Over and over again, we have seen previously high-tech business sectors utterly transformed. A few examples illustrate the point:

- Steel Production: The U.S. and Europe dominated 20th-century steel-making, but China now makes over half the world’s supply.

- Solar Panels: China controls ~80% of the global solar panel supply chain, flooding the market with affordable panels. Panel prices have dropped more than 70% since 2010.

- Rare Earth Minerals: China has a near-monopoly in rare-earth minerals. It mines and refines roughly 69% of the world’s supply, putting all U.S. and EU producers out of business.

- Batteries: China makes over 70% of the world’s lithium-ion batteries, led by giants like CATL and BYD. In 2024, battery prices in China fell nearly 30%.

The pattern is obvious: When a product or technology becomes well understood and standardized, China excels at scaling it up and wringing out cost inefficiencies. Solar panels and EVs were once cutting-edge, made only in the U.S. Today, they’re global commodities. China is the undisputed master of commodity production.

Biotech’s Big Misconception: Innovation Vs. Commoditization

How is this relevant to drug development? The root of the confusion in today’s debate seems to be that many still assume biopharma is an innovation-driven field. We’re used to thinking of drug development as the realm of breakthrough science. This was very true in the past, and, of course, biopharma companies ceaselessly repeat this in their marketing.

But for the most common drug modalities, that notion is outdated. In reality, most segments of the drug development process are commodity services. Think about it: Small molecule drugs have been around since the mid-20th century; their core chemistry and process technology were established in the 1950s.

In a similar fashion, biologic drugs — like recombinant insulin and monoclonal antibodies — were pioneered in the 1970s and 1980s. That’s nearly a half-century ago. In fact, the last major U.S. patents on monoclonal antibody production (Genentech’s famous Cabilly patents) expired in 2018 following some patent law chicanery that gave it an effective 35-year patent term rather than the normal 20 years.

Today, the exclusive know-how that once gave American companies an edge in biologics is in the public domain. The science of making a small molecule drug candidate, a novel antibody, or a GLP-1 peptide is no longer secret sauce; it’s textbook. In fact, for many critical segments of development — including GMP manufacturing and preclinical studies — even Big Pharma tends to outsource, including to China-based service providers.

In other words, making drug development with conventional therapeutic modalities has become increasingly commoditized — just like making steel, solar panels, and batteries before them.

And just like with solar panels and batteries, a commoditized process is exactly the kind of game China plays extremely well.

A Herd Of “Me-Too” Drugs

One obvious and observable consequence of this “modality commodification” process is “target herding” — the phenomenon where dozens of drug companies chase the same biological target.

Two decades ago, only a small fraction of top drug pipelines overlapped on the same targets. Today, a majority of pipelines are “herded.” In 2020, a stunning 68% of leading pharma pipelines had more than five programs pursuing the exact same target, up from just 16% in 2000. By one analyst’s count, a quarter of all industry drug programs are aimed at just 38 biological targets.

For a salient example, look at the current craze for GLP-1 analog drugs. Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide (Ozempic) opened the diet-drug floodgates in 2022, and now scores (maybe hundreds) of GLP-1 receptor agonists are jostling their way through biopharma pipelines globally. In China alone, there are at least 60 GLP-1 analogs in clinical trials (not counting generics). The same thing happened before with COVID-19 antibody drugs in 2020 and anti-PD-(L)1 antibody drugs in the mid-2010s.

Each of these drug molecules has some patentable tweak — a different molecular hook here, a dosing change there — and so in a narrow patentability sense, each is “innovative” and therefore technically patentable. Likewise, this applies for FDA regulatory exclusivity purposes.

But to any outside observer, they’re just variations on a theme — just as each snowflake is unique, but from a distance, they all look like snow. This “me-too” storm is not a sign of vibrant creativity; it’s a hallmark of a mature, commodified field where the innovative work has already been done and everyone is piling on the proven concept. Popular targets like GLP-1 have been so completely commoditized, it can be hard to distinguish this kind of branded competition from true generic competition.

In passing, it’s important to note that while target herding is terrible for the investors in such programs, it’s fantastic for consumers and taxpayers, who are the ultimate beneficiaries of competition. Even better: Sometimes, a tweak that looks small can be hugely important for subpopulations, as in the case of the proliferation of different subvarieties of insulin. Better still: Sometimes, a small tweak to a drug molecule can unexpectedly bring a profound change in its behavior. A good example of this latter point is the tweak Novo Nordisk made to its daily GLP-1 receptor agonist Saxenda (liraglutide) to create weekly-dosed Ozempic (semaglutide), which unexpectedly generated far more weight loss.

The more tweaks attempted by the industry, the better the odds of other such surprising events. In this way, target herding should be celebrated. But in general, investors chasing herded targets with commoditized drug modalities are, in effect, subsidizing the rest of us — just like all those 1990s dot-com VCs who subsidized free dog food shipping and discount Uber rides in the 2010s.

Regulatory Overhaul: China Levels The Playing Field (And Then Some)

If China’s talent for scaling commodity production is the raw fuel for the competitive fire, regulatory reforms have provided the accelerant. In 2015, China implemented sweeping regulatory changes to align with global standards and improve the regulatory environment for drug developers. China’s version of the FDA also hired hundreds of new drug reviewers to accelerate reviews (going from 150 to over 700 in just a few years).

The results were dramatic. Starting in 2015, the agency plowed through a backlog of 20,000 drug applications in just two years. By 2019, 77% of applications were expedited under priority review pathways. Today, clinical development in China is significantly faster and more efficient than in the U.S.

Part of this is simply review speed: Chinese regulators don’t have the same lengthy queues, and the 2015 reforms removed many delays. Another part is cost: Clinical trials in China can enroll patients faster (thanks to vast hospital networks and eager participants). It is also said that regulatory flexibility — a willingness to adapt and innovate on guidelines— is greater in China.

In short, China pressed the gas pedal hard on drug approvals, and it shows. Add to that China’s myriad government subsidies, and it’s easy to see why drug developers in China are sprinting ahead on what has essentially become a level technological playing field.

The Path Forward: Back To Innovation And Ingenuity

If this sounds like a story of U.S. decline, take heart: There is an answer that plays exactly to America’s historic strengths.

We probably can’t out-China China when it comes to efficiency, scale, and cost in a commoditized arena. And frankly, it wouldn’t be very inspiring if we did: The subsidies ultimately stem from financial repression that suppresses Chinese household incomes and promulgates unsustainable economic inefficiencies. We don’t want our own government to compete in that particular arena.

Instead, America’s deep strength has always been its capacity for reinvention. When one technology commoditizes, innovators here move on to the next big thing. We’ve seen it in tech (from 1970s hardware to 1990s software to 2020s AI) and in biotech before (think of the U.S. inventing monoclonal antibodies in the first place, or mRNA vaccines more recently).

The U.S. should therefore double down on fundamentally new biomedical technologies — areas where the science is still evolving, the tools are not yet standardized, and true breakthroughs (not just faster follow-on development) are needed. By specializing in the high-risk, high-reward R&D arenas that haven’t yet been commoditized, the U.S. can stay a step ahead of the copy-and-scale game.

How we do this at Lumen Bioscience is by focusing on new therapeutic modalities that are addressable only with our novel manufacturing platform and modernized clinical development approaches. Another Seattle company, Variant Bio, instead has an extremely clever way to identify novel targets that are addressable with commodified drug modalities. This lets them take advantage of China’s cut-throat, low-margin commodified drug development platforms in the same way that U.S. appliance manufacturers benefit from China’s subsidized steel exports.

Human biology is endlessly complicated, so there are endless other possible avenues for American drug developers to pursue.

What about the current hype around AI solving drug development? Is that a panacea? Advanced algorithms and AI-driven discovery are certainly exciting and can aid in research — they are already central to several clinical programs running at my company and our GMP manufacturing (in collaboration with Google). But let’s be realistic: AI won’t miraculously nullify China’s advantage in manufacturing and clinical trials. Designing cool molecules on a computer is one thing; testing them in thousands of clinical trial patients, and churning out high-quality GMP product at scale is another.

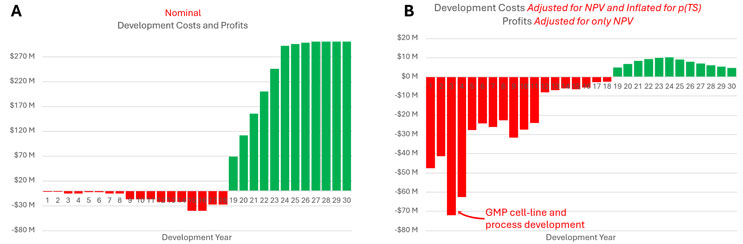

By contrast, the cost and speed of drug molecule design, the area where AI’s promise has shone brightest so far, is simply not a major factor in drug development costs. In expected value terms — from the investor’s perspective, in effect — the lion’s share of drug development cost originates from late-preclinical development, long after the molecule has been finalized. This can be easily shown through modeling (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Costs of a typical biopharmaceutical development program from preclinical development through commercial sales, with a 30-year time-horizon. Panel A: nominal out-of-pocket costs and revenues. Panel B: the same costs and revenues adjusted for the time value of money (11% discount rate) and factoring in the number of replicates required at each stage to yield a single drug launch. Model published here in the peer-review journal Military Medicine (Finrow, Brian. "The SMART Model: A Simplified Model for Assessing the Resilience of Therapeutic Program Financial Viability." Military Medicine 190.Supplement_2 (2025): 252-259.) See also this blog post from Broad Institute prion researcher Eric Minikel, to whom the author is indebted for an early version of this model’s structure.

For biologic drugs, such costs center especially on the task of creating the initial clinical trial lot (GMP cell-line and process development). Some find this surprising, but it’s a conclusion that comes up repeatedly from researchers who study such things, going back at least 20 years. Clinical trial processes (especially clinical attrition) are an even bigger driver of rising drug development costs.

Importantly, these are precisely the areas where China’s efficiency and the U.S.’s regulatory drag contrast the most. AI is dramatically streamlining lab research, regulatory drafting timelines, and data analysis, but few expect it will improve clinical attrition rates, slash Phase 3 costs, or meaningfully improve the efficiency of GMP cell-line and process development. From this perspective, concrete proposals to accelerate clinical trials (such as those suggested here, here, and here) could have a much bigger impact on U.S. drug development costs. Streamlining permitting for new drug manufacturing plants would help, too.

Regulatory modernization lacks the appeal of AI, but as China’s 2015 reforms show, they can be profoundly impactful.

Accelerating Into The Future

Ultimately, though, America’s penchant for over-regulation and bureaucracy is a relatively small factor compared with China’s other structural advantages in this newly commodified domain.

The secret is for the U.S. to zig where others zag. Specialization of labor is the flywheel of human progress — one group perfects the “commodity” processes, while another group pushes the boundary of what’s possible.

This is a tide that can raise all boats in the global economy: When U.S. scientists invent an entirely new class of therapy, the whole world (including China) can benefit, and when China’s more efficient regulatory and clinical operating environment drives down development costs, the whole world (including America) benefits from more affordable treatments.

Ultimately, America shouldn’t fear China’s thriving commodity drug development sector — making endless copies of me-too drugs like those many GLP-1 variants. That is simply the natural course of a maturing industry. Instead, the path forward for U.S. biopharma is the same as it ever was: It runs through good old-fashioned American ingenuity.

America can indeed beat China in biotech — not by playing catch-up but by leaping forward.

About The Author:

About The Author:

Brian Finrow is the founder, chairman, and CEO of Lumen Bioscience, a clinical-stage biotechnology company in Seattle.