Improve Patient Recruitment Using Behavioral Science? It's A No-Brainer, Part One

By Tatty Scott, patient engagement and recruitment professional

Behavioral science tells us we can change someone’s behavior without them even realizing it. Put a poster of eyes above an honesty box where people get hot drinks, and they’ll pay three times as much.1

What magic is this?

One of the things we struggle with in patient recruitment is changing patient behavior. For patients who have never taken part in a clinical trial before, it’s understandably scary — as humans, we don’t like change.

Generally, our recruitment approach is to try to change their mind and, ergo, their behavior by providing the right information. This aligns with the information deficit model shared by psychologists and economists. Yet a failing of the model is that better or more information doesn’t always lead to the results we desire.

Going back to the example of the honesty box, could there be another way?

In part one of this two-part series exploring ways behavioral science can improve patient recruitment and retention, we’ll consider the individual patient and how nudging their brain’s autopilot can help us change their behavior.

Don’t Look Now Descartes, But Pavlov’s Entered The Chat

In the 1970s, behavioral scientists began developing the concept of a dual process model (DPM) in the human mind, not as a physical system but as a broad descriptive brush for our two distinctive decision-making processes.2

In the model, System 1 is automatic, speedy, and effortless. It’s why we know that 2 + 2 = 4 without counting our fingers and why we salivate seeing a lemon being sliced. (Wait, did you just salivate reading the word lemon?) System 2, in contrast, is long-multiplication, abstract thinking, concentrated attention, and working problems out. It characterizes us as human.

Current thinking suggests that at least 50% and perhaps as much as 90% of human decisions are controlled by System 1.3

Wait, what? Yes, you read that correctly. It turns out that we are not quite the reflective, perspicacious beings we think we are. Like Pavlov’s dogs, we’re often on autopilot, our decisions and behaviors triggered by unconscious cues from our experience, biases, and environment.

Two System 2 thoughts on this bombshell:

- If more than 50% of our decisions are made automatically, how many potential participants are we losing because of their System 1’s preconceptions of clinical trials?

- The bestselling book Nudge by Thaler and Sunstein argues that we can manipulate the environment to reliably influence behavior without having to produce reams of information to change someone’s mind.4 (See the honesty box example, above. The nudge — the image of the eyes — connects with the customer’s System 1 and changes their experience of getting coffee and, therefore, changes their behavior.) How do we do this, though, for patients?

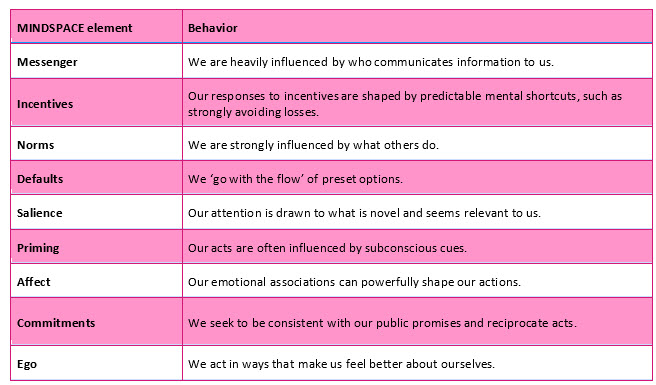

To investigate further, earlier this year, I joined an online course by Professor Paul Dolan, a behavioral scientist at the London School of Economics. Dolan developed the MINDSPACE framework, a mnemonic that identifies nine areas where our decision-making has been reliably changed by targeting System 1 (Table 1).5

Table 1: The MINDSPACE framework for behavior change5

Below, distilled from this comprehensive course and massively complex topic, is a smattering of simple and cost-effective ideas. It’s important to state here, and I cannot stress this enough, that I am not a behavioral scientist.

System 1 And Patient Recruitment

The messenger is more important than the message. In a study conducted at a sales and rentals estate agency, receptionists were asked to change how they introduced the agents from “For rentals, you need to speak to Judy” to “For rentals, you need to speak to Judy, who has over 15 years’ experience renting properties in this neighborhood.” Valuations increased by 20% and property contracts by 15%.6

Increasing Messenger Power

Humanizing information helps, too. If I learn that the PI of a trial I’ve been offered has two pugs called Pinky and Perky, is it going to make me sign up for the trial? No. But will I see the PI differently? Yes, and as a dog owner, I will instinctively feel that we have something in common; her power as a messenger has increased.

A top-notch messenger is someone with authority and expertise, someone we can trust and, importantly, someone we can relate to. We can increase the messenger power of HCPs in their recruitment endeavors by simply sharing brief bios on their research experience, along with some humanizing personal facts.

Building on this idea, and relating to the honesty box, we can help HCPs refer and recruit to trials by marking their environments as research environments. Posters in doctors’ waiting rooms stating “research happens here” and sharing details on types of research and who is involved change the environment. This small change can potentially shift patients’ confidence in the clinic’s research chops.

As marketers know, our brain is constantly filtering what it pays attention to. What wins is what is shiny and salient — i.e., something new that also makes sense. A UK Government quit smoking campaign suggested that after a set number of days, smokers would experience a 30% improvement in lung function.7 What does that even mean? (Cue System 1 searching for something more shiny and salient.) To stay engaged, what a smoker’s System 1 needed to know was what 30% will feel like — more stamina playing with the grandkids or dancing to a banging tune to impress the ladies? Also, top tip: Apparently, we are bad at processing probabilities but better at processing frequencies. So, if there’s a 1% chance of developing a genetic condition, it’s more comprehensible for us to hear “1 in 100” instead.

The Foot-in-the-Door Effect

Emotions have a huge impact on our decision-making, and brands spend small fortunes making us feel good about their products to entice us to buy them. In clinical trials, altruism is often cited as a key motivator for participation; it makes us feel good to do good. But a deeper truth is that it is conditional altruism; we’re happy feeling good about helping others as long as it is also helping us (or at very least, not harming us).8 Imagery and messaging can trigger this conditional, emotional motivation, showing that participation may bring answers for the patient as well as many others, which is a hugely noble thing to do.

Before we move on to retention, commitment — one of the nine MINDSPACE elements — is also relevant to recruitment. The foot-in-the-door effect, well-known by advertisers, seeks to persuade customers to sign up for something small, like a mailing list, as they are more likely to commit to a future purchase.9 Foot-in-the-door triggers our System 1’s urge to act consistently. As a patient recruitment strategy, spending resources to get patients onto mailing lists and research registries is a wise investment toward future recruitment, as we’ll see in part two of this series.

System 1 And Participant Retention

System 1 likes consistency, so you’d think participant retention would be a shoo-in. Instead, we have a fairly static dropout rate of around 30%.10

Making a shared or public commitment to something makes us more likely to stick to it. In a test of a new student support program, a group of students received personalized text messages encouraging them to study. In addition, their nominated study supporter also received a text and then talked to the students about their course. Students in this group were 27% more likely to pass than other students.11

In the clinical research arena, covering costs to provide research buddies, such as a member of the study team who can let participants know they’re not alone and that they are doing great, might help trial participants remain committed.

Towel Reuse

A cheaper option than research buddies to improve retention rates may be targeting social norms.

It’s common to see signs in a hotel room asking you to reuse your towels. A study found that environmental and social responsibility appeals resulted in around 30% compliance in towel reuse. But when the appeal targeted social norms by being more specific and relatable — “75% of the guests who stayed in your room (#xxx) participated in our program…” — participation increased to 49%.12

Good patient retention practice includes sending thank you letters to participants at set study junctions. Reminding patients in the thank you note that they belong within a social norm may help improve retention and at a negligible cost. The targeted social norm could be as simple as referencing the number of patients living with and managing the condition in their country or state.

In addition, beliefs can operate as commitment motivators. Reminding participants within the thank you note that they are supporting an important innovation and helping others can help rekindle any waning sense of belief.

Morgan Freeman And The Ethics Of Nudging

Fun fact: In the past, I’ve used Morgan Freeman as a kind of phantom adjudicator on my life choices. Had a few glasses of prosecco at a friend’s wedding and about to text an ex? Wait. What would Morgan Freeman say?

The choice to nudge patients as a recruitment or retention tactic is in a whole other wheelhouse. We’re already heavily regulated on what we can and cannot say. How ethical is it for us to nudge patients when the whole premise is manipulating environments to change someone's behavior without them knowing it?

Many of us who have developed patient-facing materials and social media campaigns will regularly be nudging audiences’ System 1. Using images that represent a target study population is one widespread example. Although the image may specifically attract a patient’s System 1, it isn’t coercive. Nudging follows a libertarian paternalist mindset. While nudges present choices in specific ways, no choices are taken away. If you want to confirm that you’re nudging ethically, a more reliable yardstick than Morgan Freeman for this topic is the FORGOOD framework by Lades and Delaney (2020).13

My view is that patient recruitment’s core goal is to make the patient feel safe, that they are in good hands, that they are given trial information openly by experts they can trust, and that the final decision on whether to participate is then up to them.

From Nudging Individuals To Changing A Crowd

In this article, I’ve given a rudimentary outline of how nudging patients’ System 1 may help improve recruitment and retention numbers. For me, the appeal is that interventions can be small tweaks to what we already do, meaning that improvements can be applied quickly and at a negligible cost.

Having come from a background delivering engagement in different sectors (arts, heritage, health, and education), I am a fully signed-up advocate for applying lessons from other industries to improve recruitment and retention outcomes. Adopting disciplines and ideas from behavioral science, such as intentionally engaging System 1, for me, is a no-brainer.

In part two, I add social psychology to the mix to explore the magnetic pull of groups on individuals’ behavior and show real-world examples of how groups can be drivers for maximizing behavior change.

References:

- Bateson M, Nettle D, Roberts G. Cues of being watched enhance cooperation in a real-world setting. Biology letters. 2006 Sep 22;2(3):412-4.

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011.

- Khatri, V., Samuel, B.M., Dennis, A.R., System 1 and System 2 cognition in the decision to adopt and use a new technology, Information & Management, 55, (6), 2018, pp709-724

- Thaler, R.H., Sunstein, C.R., Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness, Penguin Books, 2009

- Dolan, P. et al, Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2012 Feb 1;33(1):264-77.

- Goldstein, N., Martin, S., Cialdini, R.B., Yes!: 60 secrets from the science of persuasion. Profile Books; 2017 Apr 6.

- Dolan, P. Behavioural Science: Influencing Behaviour and Designing Decisions, Available at: https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/cognitive-psychology-employee-and-customer-behaviour/1/steps/1348909, Step 2.7, Accessed 30 April 2025

- McCann, S.K., Campbell, M.K. & Entwistle, V.A. Reasons for participating in randomised controlled trials: conditional altruism and considerations for self. 2010 Trials 11, 31

- Burger, J.M., The foot-in-the-door compliance procedure: A multiple-process analysis and review. Personality and social psychology review. 1999 Nov;3(4):303-25.

- Oakley-Girvan, I. 2023. Available at: https://acrpnet.org/2023/02/22/unique-considerations-for-patient-retention-in-decentralized-clinical-trials Accessed: 30 April 2025

- Dolan, P. Behavioural Science: Influencing Behaviour and Designing Decisions, Available at: https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/social-psychology-employee-and-customer-behaviour/1/steps/1330790, Step 4.7, Accessed 26 April 2025

- Goldstein, N.J., Griskevicius, V., Cialdini, R.B. Invoking social norms: A social psychology perspective on improving hotels’ linen-reuse programs. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. 2007 May;48(2):145-50.

- Lades, L.K., Delaney, L., Nudge FORGOOD. Behavioral Public Policy. 2020:1-20.

About The Author:

Tatty Scott is a patient engagement and recruitment professional based in Scotland. She worked as a journalist, focusing on health, and in diverse community engagement for 20 years before joining clinical trial engagement in 2015. Her favorite food is oranges, and she has a cocker spaniel named Piglet.

Tatty Scott is a patient engagement and recruitment professional based in Scotland. She worked as a journalist, focusing on health, and in diverse community engagement for 20 years before joining clinical trial engagement in 2015. Her favorite food is oranges, and she has a cocker spaniel named Piglet.