4 Steps For Representative Enrollment In Rare Disease Trials

By Mariam Badmus, clinical study specialist, gene and enzyme therapies

Representative enrollment in clinical trials is no longer an aspirational goal or a best-effort exercise. With the passage of the Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act (FDORA), sponsors are now expected to define enrollment goals based on disease epidemiology, formally linking study populations to the biological reality of the conditions under investigation.1 This shift marks a clear regulatory signal: how patients are enrolled is now inseparable from the credibility of the evidence generated.

At the same time, participant enrollment remains one of the most persistent operational challenges in clinical development. Trials continue to be delayed, downsized, or terminated due to recruitment shortfalls. Estimates suggest that nearly 30% of research sites fail to enroll a single participant, creating a massive resource drain that widens the disconnect between regulatory expectations and operational execution.2

In rare disease programs — such as gene therapies and enzyme replacements — patient populations are already small, geographically dispersed, and often managed outside traditional trial networks. In conditions such as hemophilia A, where inhibitor development risk varies across populations, enrollment shortfalls are not merely logistical; they can shape scientific interpretation.3 The challenge facing sponsors is no longer whether to pursue representative enrollment, but how to operationalize it in a way that is both feasible and scientifically defensible.

From Mandate To Method

FDORA clarifies FDA expectations but leaves open how sponsors should operationalize epidemiology-based enrollment in rare disease programs. For development teams, this creates a practical challenge of designing enrollment strategies that are both feasible and scientifically defensible in settings where every participant carries outsized evidentiary weight.

Meeting this expectation requires moving beyond recruitment tactics and toward a structured approach to evidence generation.

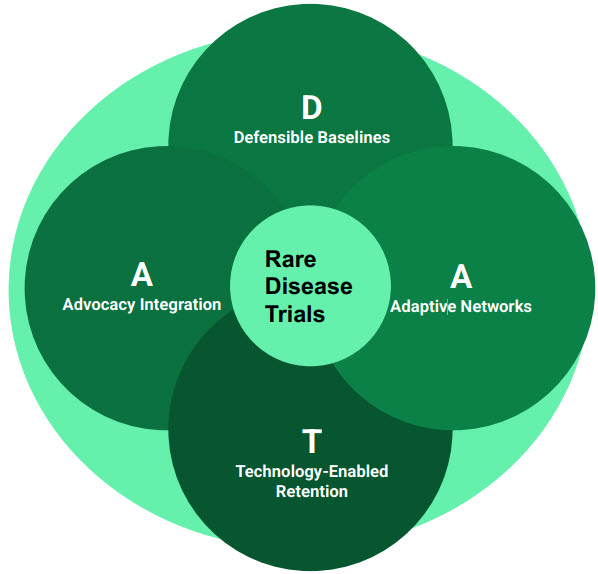

The D.A.T.A. Model

To move beyond compliance-driven enrollment and toward scientifically credible data sets, sponsors need a practical operating framework. The D.A.T.A. model provides a science-first approach for rare disease development, integrating epidemiology, access, and execution while preserving data integrity. Rather than introducing new tools, the framework reorders and connects familiar practices to meet emerging expectations for representative, data-driven enrollment across programs and modalities.

1. Defensible Baselines (D): Using RWE to Set Targets

Historically, enrollment targets have often been shaped by feasibility rather than disease epidemiology. In rare disease programs, this has sometimes led to inherited assumptions that frustrate operational teams and fail to reflect underlying biological differences. FDORA reframes this approach by explicitly tying enrollment expectations to data. As a result, the first step in the D.A.T.A. model is not outreach or site activation but the establishment of defensible baselines using RWE.

RWE allows sponsors to map the true demographic and geographic footprint of a disease. For rare metabolic disorders or enzyme deficiencies, patient populations may be unevenly distributed across regions or concentrated within specific communities due to founder effects, genetic drift, or historical patterns of diagnosis and care. By leveraging claims data, EHRs, and patient registries, sponsors can define enrollment targets that align with the FDA’s Rare Disease Evidence Principles and reflect observed disease biology.

This approach enables enrollment strategies that are both realistic and defensible. When recruitment goals are grounded in epidemiologic and real-world data, rather than inherited assumptions or internal mandates, sponsors strengthen regulatory credibility while protecting scientific integrity.

FDORA also recognizes that epidemiology-based enrollment may not be feasible in every rare disease context. For conditions with extremely small, poorly characterized, or geographically constrained populations, representative targets may be structurally unattainable despite rigorous planning. Within the D.A.T.A. framework, this does not represent a failure of enrollment strategy but a conclusion reached through it. Defensible baselines derived from RWE allow sponsors to demonstrate when deviations from representativeness reflect biological and epidemiologic constraints rather than operational limitations, enabling transparent and credible regulatory dialogue.

2. Adaptive Networks (A): The Hub-and-Spoke Solution

Historically, advanced therapeutic trials have been concentrated at major academic medical centers due to the complexity of administering viral vectors, enzyme infusions, or other specialized interventions. While this centralization is often necessary for safety and oversight, it can also narrow access by limiting participation to patients who live near these centers, overlooking eligible patients managed in community settings.

To address this gap, the D.A.T.A. model emphasizes adaptive site networks built around a formal hub-and-spoke structure. In this model, centers of excellence serve as treatment hubs, while community physicians act as spokes, identifying and referring appropriate patients. Importantly, this approach moves beyond informal outreach or ad hoc referrals. It requires operational partnerships that enable community hematologists, neurologists, or other specialists to function as integrated contributors to the trial, even if they are not full investigative sites.

Operationalizing this model starts with simplifying the referral pathway. Community physicians are often time-constrained and lack the infrastructure to navigate complex eligibility criteria or study logistics. Sponsors can reduce this friction by deploying streamlined prescreening tools and dedicated support resources to coordinate referrals, assessments, and patient transfer to the appropriate hub. By lowering the operational barrier to participation, adaptive networks expand trial reach and help surface patients who are clinically eligible but historically disconnected from traditional research pathways.

3. Technology-Enabled Retention (T): Solving the Long Haul

In rare disease trials, the burden of participation does not end at enrollment. Advanced therapeutics often require extended long-term follow-up to assess durability and safety, sometimes spanning a decade or more. For families who live hours from a trial site, repeated travel over many years can become the deciding factor in whether they remain in a study. Over time, this burden contributes to differential attrition, with downstream effects on the completeness and interpretability of long-term safety data.

Technology-enabled retention offers a practical way to address this challenge. While the initial administration of complex therapies may require inpatient care or specialized facilities, much of the subsequent monitoring does not. Remote data capture, telemedicine check-ins, and home-health nursing visits for sample collection can reduce unnecessary site visits without compromising oversight or data quality.

Operationalizing these tools shifts retention from a logistical hurdle to a design consideration. Replacing routine in-person visits with remote assessments or mobile nursing support can significantly reduce time, travel, and indirect costs for participants, improving long-term engagement across diverse socioeconomic settings. By lowering the burden of continued participation, sponsors can preserve follow-up completeness and strengthen the credibility of long-term safety data sets — an increasingly important consideration as regulators scrutinize attrition patterns in extended follow-up studies.

4. Advocacy Integration (A): The Protocol Design Partner

The final pillar of the D.A.T.A. model is advocacy integration. In rare diseases, patient advocacy groups (PAGs) play a central role in shaping trust and engagement. Yet operational teams often engage these groups only after enrollment challenges emerge, when opportunities to influence study design have already passed.

To support representative enrollment, advocacy engagement must begin earlier, during protocol concept and synopsis development. Mistrust in medical institutions remains a barrier for many communities, and this mistrust is often reinforced by protocol designs that fail to reflect real-world disease presentation. Restrictive eligibility criteria, rigid visit schedules, or unexamined baseline assumptions can unintentionally exclude patients who are clinically representative but operationally disadvantaged.

Integrating PAG leaders into early protocol discussions allows sponsors to surface potential barriers before they become embedded in the study. Questions such as whether visit schedules impose undue time or economic burden, or whether exclusion criteria inadvertently filter out specific subpopulations, can be addressed proactively. By incorporating this perspective up front, sponsors can optimize protocols to support inclusion by design, and this strengthens both enrollment feasibility and the relevance of the resulting data.

The Path Forward

The FDORA mandate is not simply another regulatory hurdle; it represents a course correction toward better science. In the era of advanced therapeutics, where genetic background and real-world context can meaningfully influence safety and efficacy, representative enrollment is inseparable from data integrity. How trials enroll patients now directly shapes how results are interpreted, trusted, and applied.

For clinical research professionals and operational leaders, the challenge is to build trials that are as innovative in their execution as they are in their pharmacology. The D.A.T.A. model offers a practical way forward. By grounding enrollment targets in defensible baselines, expanding access through adaptive networks, reducing attrition via technology-enabled retention, and integrating patient advocacy early in protocol design, sponsors can move from reactive recruitment to deliberate evidence generation.

In rare disease development, where every participant carries scientific weight, this shift matters. Trials designed with representativeness in mind are better positioned to deliver data that regulators can trust, clinicians can apply, and patients can recognize as relevant to their lived experience. In this sense, FDORA does not merely raise the bar for enrollment, it clarifies the path toward more credible, inclusive, and durable clinical evidence in modern drug development.

References:

- Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022. Section 3601-3607. Washington, DC: 117th US Cong; 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2617/text

- CSSi. "2025 Trends In Patient Recruitment: From Disruption To Precision." Clinical Leader. Accessed January 2026. https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/trends-in-patient-recruitment-from-disruption-to-precision-0001

- Ahmed AE, Pratt KP, et al. Race, ethnicity, F8 variants, and inhibitor risk: analysis of the "My Life Our Future" hemophilia A database. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21(4):800-813. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36696179/

About The Author:

Mariam Badmus is a clinical study specialist and researcher in the biotechnology industry, working in clinical development for rare and genetic diseases. Her work spans gene therapies, enzyme substitution treatments, and other biologic therapies used in rare and genetic diseases. She focuses on clinical trial operations and regulatory considerations to support credible, regulator-ready evidence. Her background includes preclinical research in rare and genetic disease models at UCSF, which informs her translational approach to clinical trial design. She holds a master’s degree in translational medicine from UC Berkeley and UCSF and a bachelor’s degree in pharmacy.

Mariam Badmus is a clinical study specialist and researcher in the biotechnology industry, working in clinical development for rare and genetic diseases. Her work spans gene therapies, enzyme substitution treatments, and other biologic therapies used in rare and genetic diseases. She focuses on clinical trial operations and regulatory considerations to support credible, regulator-ready evidence. Her background includes preclinical research in rare and genetic disease models at UCSF, which informs her translational approach to clinical trial design. She holds a master’s degree in translational medicine from UC Berkeley and UCSF and a bachelor’s degree in pharmacy.