The Best Project Management Methodology Isn't Traditional Or Agile — It's Both

By Aurea M. Flores, Ph.D., BS Pharm, CCRP, CHRC, CHC, CHPC, CCEP, PMP, PMI-ACP, RQAP-GCP

Traditional project management methodology follows a linear progression from beginning to end, which should theoretically work for clinical trial development. However, in my experience as a former director of clinical research operations, this method yielded a success rate for timely trial opening of less than 5%.

For some academic institutions and large health systems conducting clinical trials, the expectation is to open trials within 30 days from receipt of the regulatory essential document package. Others would like the timeline to be 42 days. However, neither timeline has ever been validated; they are purely anecdotal. During my 25-plus years of clinical trial experience, I have seen only one trial open at 30 days, as determined by the execution of the clinical trial agreement. However, the trial had many deficiencies that were never adequately addressed throughout the trial life cycle. On the other hand, I once came across a trial that took 13.5 months to open. Somewhere in the middle is the sweet spot.

As I explored solutions to get closer to these 30- and 42-day timelines, I came across Agile methodologies — and the data supporting their use was astounding. According to the Standish Group's Chaos Report (2020), there is a striking difference in the success rates of projects executed under these methodologies from 2013-2020. With the traditional method, 13% of trials successfully started on time. Using Agile methodology, the success rate rose to 42%.

To better understand these two methods, let’s take a look closer at their composition.

What Is Traditional Project Management Methodology?

Traditional, or waterfall, methodology has been around since the 1970s. It comprises five phases:

- Requirements — Determine the resources required. Perform a risk assessment. Determine what each team member will work on and at what stage. Establish a timeline for the entire project, outlining how long each stage will take.

- Design — Create schedules and project milestones. Determine the exact deliverables (such as committee approvals, contracts, agreements, budgets, etc.). Create designs and/or blueprints for deliverables.

- Implementation — Create an implementation plan. Collect any data or research needed for the build. Assign specific tasks and allocate resources among the team.

- Verification — Run a participant simulation. Determine which quality (QA) metrics to track.

- Maintenance — Ensure quality. Submit adverse event information. Manage risks and amendments.

What Is Agile Project Management Methodology?

Agile project management is an iterative approach to delivering a project, which focuses on continuous releases that incorporate customer feedback. The ability to adjust during each iteration promotes velocity and adaptability. There are five Agile frameworks.

Scrum

Scrum is one of the earliest frameworks in Agile, dating back to 1986, and it is described as a holistic approach to cross-functional development teams moving through multiple overlapping phases, allowing increased speed and flexibility. Scrum relies heavily on the power of a self-organizing, self-directing team and team collocation, which is a weakness of clinical trial teams.

eXtreme Programming (XP)

Originating in software programming, XP takes best practices, tried and proven, to the next level. XP has several assumptions, including that one unified client viewpoint exists. When this assumption is correct, XP is productive. Unfortunately, in clinical trials, there is not a unified viewpoint. We will explore this idea later.

Lean Software Development (LSD)

The Lean framework concerns itself with eliminating any unnecessary burden or overhead from the project development process. Lean is about creating value and reducing burdens experienced every day by those involved in the development process. Lean is most consistent with process improvement. One of the outcomes of a Lean framework is cost savings.

Kanban Basic Practices

Kanban is a Japanese word that means “signal card.” The card signals an upstream process to produce more. It identifies bottlenecks and eliminates them based on the “theory of constraints,” which identifies the most important limiting step in a project that stands in the way of achieving the goal. In this case, it's opening the trial on time. It is also a “pull” system that produces deliverables by changing them incrementally at a sustainable pace. In context, needed deliverables (e.g., clinical trial protocol, budget, clinical trial agreement) are provided based on the project lifecycle. Kanban and Lean platforms complement each other.

Whether Using Agile Or Traditional Methodology, Problems Persist. Why?

All these Agile platforms have different players/stakeholders associated with the different processes, which would appear to align with the clinical trial specialties. However, during my experience using Agile — and contrary to the Standish Group’s report — I experienced the same results as with the traditional method. The question is: Why?

Few Follow The Rules Of Engagement

At the root of challenged and failed clinical trial implementation projects is the lack of standardization in understanding roles and responsibilities and effectively integrating project managers from different partners. Furthermore, in clinical trial implementation, there are usually at least two project managers (at the sponsor, CRO, and/or site level) with uneven project viewpoints. The lack of a unified vision for the project comes from all partners involved and is usually the result of miscommunication and misunderstanding.

Therefore, projects must always observe basic rules of engagement:

- Everyone participates.

- Everyone has an equal voice.

- Everyone has a valuable contribution to make.

- Respect differences.

- Honor confidentiality and privacy within the team.

- Attack issues, not people.

But often in clinical trial implementation, the top brass makes decisions, in many cases disregarding input from knowledge workers who better understand clinical trial process flows and regulatory requirements. I’ve found that in clinical trial implementation, like healthcare, there is a clear hierarchy. Medical doctors’ (MDs) opinions have the most weight, regardless of the topic, followed by those of administrators (MBA holders and C-suite roles). Many professionals with expertise but without the MD/MBA/C-suite credentials feel intimidated to render their opinions because they find themselves in a no-win situation. That is, their opinions and recommendations may be valid, but if disagreed upon, may create some issues in the workplace. Therefore, my experience is that the rules of engagement are seldom implemented or followed.

Compounding that issue and contributing further to project mismanagement and missed deadlines is the lack of reputable knowledge and expertise among CRPs. Although clinical trials are highly regulated, the people responsible are not. Healthcare professionals are highly regulated and licensed to perform their duties clearly stated in laws within the jurisdictions these professionals operate, e.g., physicians, nurses, pharmacists, etc., and their training involves credentialed classroom education as well as formal mentoring. However, in many cases, CRPs are trained by other professionals who may not be competent in clinical research laws, regulations, and guidelines.

One of the great things about clinical research professionals is that there is true diversity of thought and experience. I have worked with clinical trial professionals from all backgrounds — teachers, technicians, doctoral candidates, business professionals, nurses, accountants, etc. However, the industry fails them when there is no adequate, structured, credentialed, and free training.

Yet, 21 CFR Part 312.53(a) explains that a “sponsor shall select only investigators qualified by training and experience as appropriate experts to investigate the drug.” Selection criteria should include the following:

- The investigators have experience in the disease state to be evaluated in the clinical trial.

- The investigators have an appropriate pool of potential participants.

- The investigators understand applicable laws and regulations.

- The investigators have the infrastructure to support and comply with the above.

Most sponsors concentrate on (a) and (b), and do not place as much importance on (c) and (d). I’ve observed that most investigators lack comprehensive clinical investigator training and instead rely on the clinical research infrastructure in place at the site. For many small sites (e.g., medical clinics) there are not enough resources, in number and expertise, to appropriately support and comply with applicable laws and regulations.

Then, in 21 CFR Part 312.60 General Responsibilities of Investigators, it states that an “investigator is responsible for ensuring that an investigation is conducted according to the signed investigator statement, the investigational plan, and applicable regulations; for protecting the rights, safety, and welfare of subjects under the investigator's care; and for the control of drugs under investigation. An investigator shall obtain the informed consent of each human subject to whom the drug is administered…”

Most investigators have extensive experience and are very capable of caring for patients with the disease to be evaluated in the clinical trial. However, most also overestimate the number of potential trial participants available to participate. One of the root causes for inadequate enrollment is that investigators often become very excited about the science but do not conduct a thorough review of the eligibility criteria and perhaps do not understand their patients’ availability to participate.

Creating Consistency Among The PI And Sponsor With The Waterfall Template

For both the sponsor and investigator, there should only be one project management waterfall template with one communication plan and one risk assessment plan dedicated to the project. In my experience, there is seldom a communication plan, and rarely do sponsors and sites perform risk assessments to ensure quality and compliance.

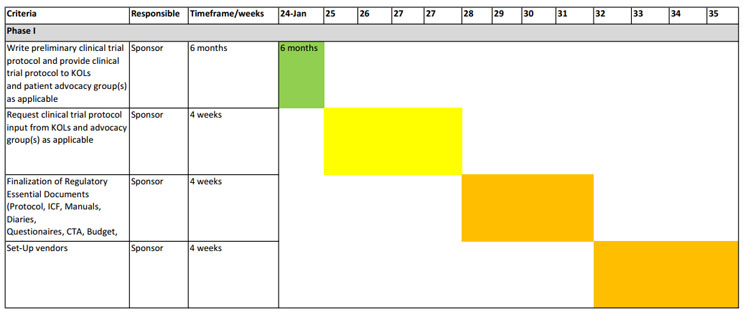

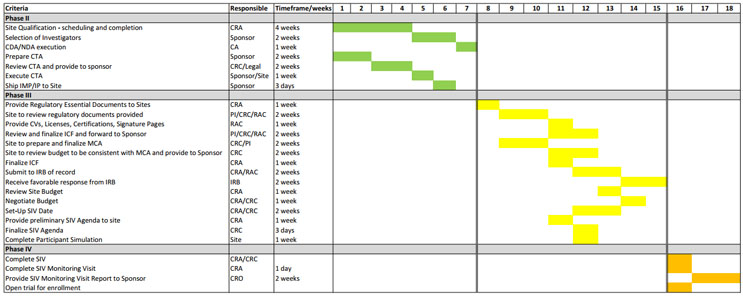

Figures 1 and 2 show a comprehensive representation of a combined waterfall template. This template is not one-size-fits-all and the timelines might be ambitious for some, but it’s a solid start for those looking to revamp their project management approach. The key points are to reasonably map the process required to open a trial and for the teams to abide by the timelines, whatever they may be. Consider this: Is it better to open a trial in 30 or 42 days with deficiencies that may or may not be adequately resolved or in 4½ months where compliance and quality can be ensured?

The waterfall template in Figure 2 is feasible if Agile concepts are integrated with traditional project management. Examples include:

- Follow the rules of engagement.

- Create and maintain a self-organized, self-directing team (Scrum).

- Most of the work takes place the day before a standing meeting.

- The right team is determined by:

- Ability – What specific competencies do the team members provide?

- Availability – What is the team members’ availability, and what are their competing commitments?

- Cost – How appropriate is the team members' cost given the budget constraints?

- Chemistry – How well do team members’ work styles align with the team culture and environment?

- Experience – What related work have the team members done? Under what time and quality constraints?

- Ensure a unified client viewpoint (eXtreme Programming).

- Work on the waterfall template together.

- Integrate continuous process improvement (Lean).

- This step is especially useful if timelines and product quality are not attained as per the proposed project life cycle.

The communication plan should identify the stakeholders and the method and frequency of communication. A frequency greater than weekly may cause delays in the project. More importantly, stakeholders should hold each other accountable for actions associated with the criteria listed in the waterfall template.

Risk assessment can be complex. On one hand, risks should be identified and addressed to ensure implementation takes place as planned, while a clinical trial-specific risk assessment should be completed before finalizing the regulatory essential document package.

The Best Recipe For Trial Implementation Success

Ultimately, it isn’t traditional or Agile project management methodologies alone that can determine the success of opening a clinical trial. Rather, it’s developing a hybrid methodology as well as understanding the internal processes, allowing an equal voice to all team members, assembling the right team, understanding and agreeing on the project vision, and not being fearful of adjustments that together make a successful clinical trial implementation.

References:

- A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge. PMBOK Guide 7th Ed. Project Management Institute

- Agile Almanac, John Steinbeck 1st Ed. GR8PM, Inc.

About The Author:

Aurea Flores is a clinical research professional with over 25 years of experience. She is a licensed pharmacist and was awarded a Ph.D. in pharmacology & toxicology with an emphasis on drug metabolism and chemical carcinogenesis. She has conducted/supported clinical trials in a variety of areas (oncology, cardiology, neurology, gastroenterology, bariatrics, pediatrics, and others) with an emphasis on patient safety, operations, quality, and regulatory compliance. She is a Certified Clinical Research Professional (CCRP-SoCRA), Project Management Professional (PMP-PMI), and Agile Project Manager (PMI-ACP), and is Certified in Healthcare Research Compliance (CHRC-HCCA), Certified in Healthcare Compliance (CHC-HCCA), Certified in Health Privacy Compliance (CHPC-HCCA). She is also a Certified Compliance & Ethics Professional (CCEP-SCCE) and a Registered Quality Assurance Professional in Good Clinical Practice (RQAP-GCP/SQA). She is a speaker at national meetings and consults in areas of clinical research operations, project management, healthcare and research compliance, and quality assurance.

Aurea Flores is a clinical research professional with over 25 years of experience. She is a licensed pharmacist and was awarded a Ph.D. in pharmacology & toxicology with an emphasis on drug metabolism and chemical carcinogenesis. She has conducted/supported clinical trials in a variety of areas (oncology, cardiology, neurology, gastroenterology, bariatrics, pediatrics, and others) with an emphasis on patient safety, operations, quality, and regulatory compliance. She is a Certified Clinical Research Professional (CCRP-SoCRA), Project Management Professional (PMP-PMI), and Agile Project Manager (PMI-ACP), and is Certified in Healthcare Research Compliance (CHRC-HCCA), Certified in Healthcare Compliance (CHC-HCCA), Certified in Health Privacy Compliance (CHPC-HCCA). She is also a Certified Compliance & Ethics Professional (CCEP-SCCE) and a Registered Quality Assurance Professional in Good Clinical Practice (RQAP-GCP/SQA). She is a speaker at national meetings and consults in areas of clinical research operations, project management, healthcare and research compliance, and quality assurance.