The Future Of Clinical Trials Is Neurodiverse

By Brianna T. Polite

Clinical research has a talent problem, and the future of this industry depends on how we respond. It’s not just about recruitment or retention. It’s about the voices we’re not hearing. And yet, despite the growing conversation around equity, one dimension remains under-addressed: cognitive diversity. It’s about the voices we’re not hearing, the minds we’re not cultivating, and the systems we’re not questioning.

As someone with AuADHD (autism and ADHD) who has spent years monitoring global trials, I’ve seen how neurodivergent professionals often work twice as hard to mask their differences, while offering insights that, if embraced, could improve protocol compliance, reduce delays, and elevate participant experience.

So why is neurodiversity still missing from clinical trial strategy?

What Is Neurodiversity?

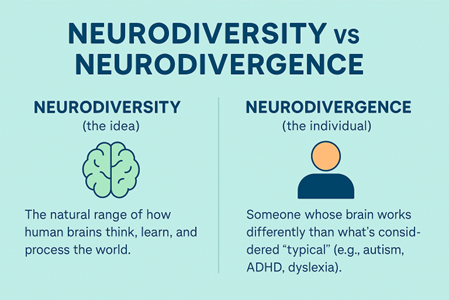

Harvard Health defines neurodivergence as the idea that neurological differences are natural variations of the human genome rather than disorders to be cured. These differences often shape how people think, learn, and interact with the world, offering unique strengths and perspectives. These include autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other cognitive profiles that diverge from what is considered neurotypical.

A critical distinction to the conversation is that neurodiversity describes the concept, while neurodivergence describes the individual experience. Understanding the difference helps us design systems that recognize both.

The Operational Blind Spot

Most workforce frameworks in clinical research are built on conformity. SOPs, timelines, and KPIs are essential to quality but often come at the cost of innovation. When everyone around the table thinks the same way, we miss what’s right in front of us.

Neurodivergent professionals often bring a distinct advantage:

We see patterns others miss, like inconsistencies in documentation or silent process bottlenecks.

We challenge protocol logic that might otherwise go unquestioned, often because ADHD or autistic thinking favors system-level analysis and detail scrutiny.

We anticipate site and participant-level challenges before they escalate, thanks to heightened sensitivity to friction, ambiguity, or sensory and cognitive overload in the trial journey.

In my work with research teams and emerging tech platforms, I’ve seen how neurodivergent minds elevate trial quality, often in ways traditional systems don’t capture. For example, I questioned an overly technical section of the ICF. After working with the study team to simplify the language during the next protocol amendment, we saw a notable increase in site staff understanding, resulting in fewer questions from the site staff during the consenting process, the most important step, in my opinion, in a clinical trial. I am especially attuned to contradictions that surface between protocols, ICFs, site manuals, and data systems. When language or expectations don’t align, it creates unnecessary risk, confusion, and rework. Spotting these disconnects early can mean the difference between a minor correction and a full protocol amendment, which is sometimes not in the budget. We’re the ones who flag participant burden before it affects retention, who question the protocol language that could confuse coordinators, who ask the operational “what ifs” that prevent costly deviations. These aren’t quirks; they’re competencies.

What’s Missing From SOPs

We say we want innovation, yet many neurodivergent professionals are navigating:

vague communication that leads to misinterpretation or burnout. Examples include receiving visit instructions where expectations were implied but never explicitly stated, leaving room for misalignment and unnecessary stress.

rigid systems that penalize cognitive difference, such as forms without a character limit guide or draft review feature, which leads to wording misinterpretation and retraining, not because of incorrect content because expected formatting wasn’t mirrored.

unspoken stigma, even within “inclusive” teams where ideas are dismissed or questioned more intensely once a team becomes aware of someone’s diagnosis, even if that individual had previously been praised for their contributions.

Without intentional support, starting at onboarding and extending into leadership development, we risk losing some of the most systems-minded, detail-oriented contributors in our field. And the impact doesn’t stop at staff. It reflects in the patients we fail to reach. The problem isn’t just who gets hired. It’s how trials are built.

A Strategic Response, Not An Accommodation

Neurodiversity in clinical trials isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s a strategy. It belongs at the core of how we structure teams, design protocols, and evaluate performance.

Here are a few ways to move from awareness to action:

Embed neurodiversity education in onboarding, training, and management frameworks.

Apply universal design principles, an approach that aims to make systems, environments, and materials accessible and usable by all people, regardless of ability, to operational workflows and documentation.

Offer flexible communication tools, quiet zones, and asynchronous work options.

Let’s stop admiring the problem. Let’s build solutions.

How Sponsors And CROs Can Lead

Sponsors, CROs, and biopharma organizations are already beginning to implement neuro-inclusive practices through Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs), recognizing both the operational value and the ethical imperative. They are uniquely positioned to accelerate this shift. Here’s how:

Audit performance reviews and attrition patterns for neurodivergent bias.

Build structured feedback loops to integrate neurodivergent insights by including a dedicated space in debriefs, such as lessons learned sessions, retrospectives, or team huddles, where contributors can flag operational friction or communication overload. This is especially valuable when neurodivergent team members are uncomfortable speaking up spontaneously. Written surveys or anonymous input options can also help surface these insights in more accessible ways.

Invite neurodivergent professionals to participate in protocol design, patient journey mapping, and feasibility planning.

This isn’t about accommodation. It’s about foresight.

The Competitive Edge We’ve Been Missing

Neurodivergent professionals are already embedded in clinical research, managing visits, flagging risk, and training teams. However, we often do it silently and at a significant personal cost. Many neurodivergent professionals experience chronic cognitive overload, not from the work itself, but from the effort it takes to navigate systems not built with their processing style in mind. They may internalize confusion or ambiguity as personal failure, mask their needs to avoid being labeled “difficult,” or hesitate to speak up without a clear structure that welcomes input. Over time, this leads to decision fatigue, misinterpretation, emotional exhaustion, and in some cases, quiet disengagement, not due to lack of care, but lack of safety. When leaders make space for diverse cognitive contributions, trial outcomes and team resilience improve.

If we want clinical trials that are efficient, equitable, and truly future-ready, we must design them for the full range of human cognition.

Neurodiverse minds aren’t the exception. We’re the edge.

Ready To Build Neuroinclusive Systems? Start Here

- Audit your SOPs for language that assumes one cognitive processing style.

- Include neurodivergent reviewers in protocol feasibility assessments.

- Train team leads in cognitive equity, not just interpersonal DEI.

Organizations that lead on this front won’t just meet metrics; they will set the standard. The future of research is more inclusive, adaptive, and human by design. The future of clinical trials will not be built on sameness; it will be built on systems bold enough to recognize cognitive difference as an operational edge.

References:

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2021). Neurodiversity and mental health. Harvard Medical School. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/neurodiversity-and-mental-health-202111222649

About The Author:

Brianna Polite is a Master of Public Health candidate, a clinical strategist, and the founder of a boutique consulting firm. As a senior clinical research associate, she blends lived experience of AuADHD with operational expertise, building systems where neurodivergent minds don’t just survive, they lead. Her work reimagines trial design, site strategy, and leadership development to reflect the full spectrum of human cognition. Brianna doesn’t just follow protocols; she redesigns them.

Brianna Polite is a Master of Public Health candidate, a clinical strategist, and the founder of a boutique consulting firm. As a senior clinical research associate, she blends lived experience of AuADHD with operational expertise, building systems where neurodivergent minds don’t just survive, they lead. Her work reimagines trial design, site strategy, and leadership development to reflect the full spectrum of human cognition. Brianna doesn’t just follow protocols; she redesigns them.