The Making Of A Patient Advocate For The Clinical Trials Enterprise

By Bray Patrick-Lake, Duke Clinical Research Institute

As a sea change has occurred over the last several years embracing patients as key stakeholders critical to clinical trial success, patient advocates who are knowledgeable about research have been increasingly sought after. Questions have been lightheartedly raised about how we “clone” the patient stakeholders who’ve made impact in the clinical trials enterprise (CTE) to date or create educational programs for the next generation of patients who express interest in getting involved.

While we can note key characteristics that may help identify future research advocates, developing advocates is not as simple as asking patients to read through PowerPoint presentations on “How to Be a Patient Advocate” or “Patient Engagement 101.” Growth and development of advocates takes commitment to co-learning by other stakeholders in the CTE, repeated interactions with and exposure to clinical trial issues through the lenses of others, candid discussion about what’s driving behavior, and, most importantly, listening to patients about what’s most important to them. There are no didactic presentations or transactional approaches that can be substituted for respectful partnerships, dedication to mentoring, and working hand-in-hand with patient advocates.

The Key Ingredients To Successful Advocate Identification And Development

There are four key characteristics of successful research advocates: passion, curiosity, desire for change, and initiative. The most important factor to becoming an effective advocate is passion — the fuel in the quest for change. Usually there is a circumstance that taps into a patient’s passion and motivates one to become activated around research. Seek the patients and caregivers who ask a lot of questions or seem unsatisfied by the state of the science, and invite them to become more engaged in the CTE.

In my case, I was a patient who was out of treatment options desperately seeking relief when I self-referred to a clinical trial via clinicaltrials.gov. My treating physicians in two different specialties knew about the ongoing trials, yet never referred me. I was determined to investigate new treatments and passionate about understanding the state of the science. Unfortunately, the trial I enrolled in was later aborted for low and slow enrollment due to fatal flaws that likely could have been addressed if patients had been engaged in the design phase. To date no data has ever been published or shared with the participants, thus breaking the implied contract of research about participation contributing to general knowledge that may be used to help patients like myself. This spurred me to action to reach out to my trial investigator to ask why and how this was allowed.

Investing In Patient Partners

My investigator was initially taken aback by my inquiry but was also frustrated with the circumstances and unhappy that trial participants had been treated so poorly. He listened to my concerns and helped me understand the players and regulations governing the space. I had been reading through the consent forms again and again trying to make heads or tails of the roles and responsibilities of the sponsor, the institutional review board, the study site, the clinical site, the investigator, and the FDA, but found it all very confusing. He took time out of his busy schedule to talk to me, and we engaged in a dance of trust-building exchanges and candid discussions about the issues, which over time revealed our mutual frustrations. These frustrations translated to aligned goals for changes we’d like to make to the disease area and clinical trial ecosystem. The interactions with my investigator also helped me understand opportunities to be productive in the CTE and convert the energy of my frustration to positive action and ultimately change.

While I read a lot of material online, participated in free online trainings, and even brushed up on underpinning research concepts like biostatistics, I needed to work with a research mentor to understand the nuances of the science and clinical trials. In supporting my learning and development, my investigator shared scientific articles and presentations I could not otherwise access and we talked through concepts like the p value. He reviewed articles and testimony I wrote and provided constructive criticism. We later co-wrote articles, and he connected me with a publisher of a book on my condition that led to the opportunity to submit a chapter on the patient perspective, which was groundbreaking for the space.

Once my investigator realized I was committed to educating myself and serious about taking action in the space, he helped me establish credibility with other stakeholders by including me in panel discussions or dinners where I could share patient perspectives and build allies and relationships with experts, who at first were suspicious or fearful of my intentions as a jilted trial participant. He also helped me think through how I could contribute across the continuum1 and shared insights about the hidden rules, dynamics, and etiquette of the forums I was trying to enter so I could participate more successfully. In essence, I brought the passion, curiosity, and activation energy necessary to make positive changes for patients; he listened, guided me, provided exposure to thought-leaders in the field, and opened my eyes to the inner workings of clinical trials.

Figure 1: The evolution of advocate growth and activation

Advocate Evolution

In graduating to the next phase of advocacy, I wanted to share what I was learning with others in an effort to make the road to treatment and improved health easier for patients like myself. I activated first by connecting with other patients on social media and creating a Facebook group for my condition. This grew into a nonprofit disease advocacy foundation when other patients expressed a commitment to the mission and vision. My investigator agreed to serve on the medical advisory board for free and helped the tiny, patient-led organization attract other medical experts to the board, as well as connect with other clinician investigators and industry sponsors working in the same space. He and the other experts helped the foundation develop scientific content by providing research updates and recording videos about the condition and clinical trials.

This engagement in the science led to the foundation developing and raising financial support for a multi-stakeholder scientific summit where industry, academicians, regulators, and patients came together to develop a research and regulatory road map that was responsive to patients’ unmet needs and desire for improved access to new treatments. The foundation and its medical advisors also went on to author a patient’s guide for the condition with information from the summit, providing unbiased educational content and raising awareness about the state of the science and clinical trials in the space.

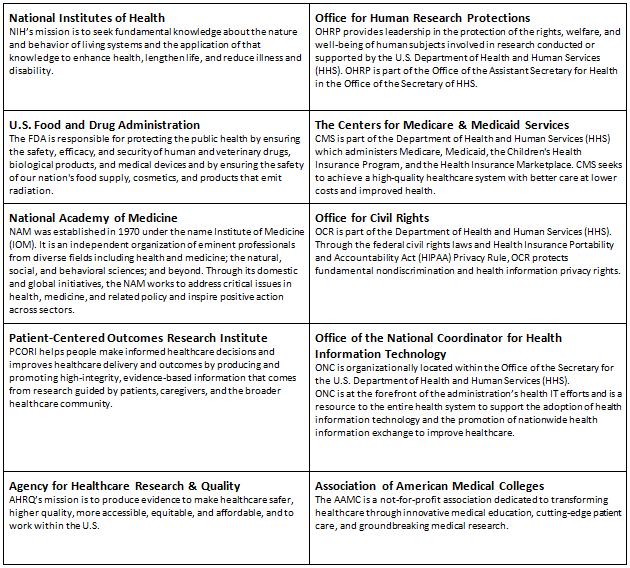

After doing what I could for my disease area, I became engaged in consortia activities related to improving the quality and efficiency of clinical trials2 when I realized there were larger issues affecting patients that no one patient or patient group could take on themselves. I also began serving as a patient representative and grant reviewer for national agencies.3-4 These experiences provided invaluable education and professional development, giving me access to a cadre of key opinion leaders, new knowledge, and perspectives of industry, academic researchers, and government representatives, paired with the opportunity to roll up my sleeves and work alongside them to resolve specific issues; this is where the real magic happens.

Figure 2: The national research ecosystem

Although my disease area did not have this support, industry sponsor programs like Celgene’s Patients’ Partners have recognized the importance of sharing knowledge with patient stakeholders and investing time and resources to support co-learning by hosting a series of educational webinars and supporting conference events that facilitate cross-sector knowledge exchange, for example.

Finally, I climbed to the ultimate rung on the research advocacy ladder. This occurs when an advocate can free oneself from the tyranny of living with disease and the burden of day-to-day disease advocacy foundation operations to develop a vision for a new way of doing things. Thorough understanding of the roles and interests of the players in the national ecosystem was required for competent participation at this level. This understanding came mostly from repeated exposure through multi-stakeholder workshops and roundtables on clinical trial issues that waived registration fees and supported advocate travel. When this final stage of metamorphosis takes place, the advocate can bring energy and passion to work in cross-sector and multi-stakeholder initiatives to design new frameworks for patient engagement in clinical trials, policies, and programs that catalyze new systems and ways of doing research.

In sum, key characteristics can help identify patient partners who may become knowledgeable and skilled research advocates, but their growth and skillful contribution are highly dependent on co-learning and investments made by other stakeholders in the CTE.

References:

- https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/files/pgctrecs.pdf

- www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org

- https://www.fda.gov/forpatients/about/ucm412709.htm

- https://www.pcori.org/engagement/engage-us/become-merit-reviewer

About The Author:

About The Author:

Bray Patrick-Lake, MFS, serves as the director of stakeholder engagement at the Duke Clinical Research Institute. She is a member of the Board on Health Sciences Policy for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and serves as an FDA patient representative and PCORI reviewer. She can be reached at bray.patrick-lake@duke.edu.