The One-And-Done Investigator: A Clinical Trial Story

By Paul Ivsin

Never let the facts (as Mark Twain famously never said) get in the way of a good story.

Clinical research has a lot of stories. Most of our stories have, at best, an awkward relationship with facts.

One story I keep hearing is the story of the “one-and-done investigator.” The story goes: An enormous number of physicians who have signed up to become principal investigators have now disappeared from the research world forever after experiencing just one clinical trial. Trials have just gotten so complex, inefficient, and unrewarding that PIs are leaving the field en masse and heading back to more fulfilling work, like navigating insurance prior authorization paperwork.

The one-and-done investigator exodus — often claimed to be as many as 50% of PIs — is usually framed as a looming existential threat to clinical trial operations that requires immediate attention. Here’s how I had it earnestly explained to me on LinkedIn just last week:

“[T]here are significant numbers of ‘one and done’ investigators given the hurdles one faces in conducting clinical research. Without the resource backing of academia or the infrastructure of a well-established private research facility a physician attempting to get into clinical research faces a multitude of challenges. Without intervention, the ability to get new trials launched will continue to rise in difficulty.” (Emphasis mine.)

I get why this story is popular! Trials do seem more complex, inefficient, and unrewarding. There does seem to be an element of not learning from our past mistakes. I can practically hear our once-enthusiastic physician leaving research and muttering to herself about returning to the simple joys of getting her 10,000 daily Epic clicks in.

There are only two little problems with this story.

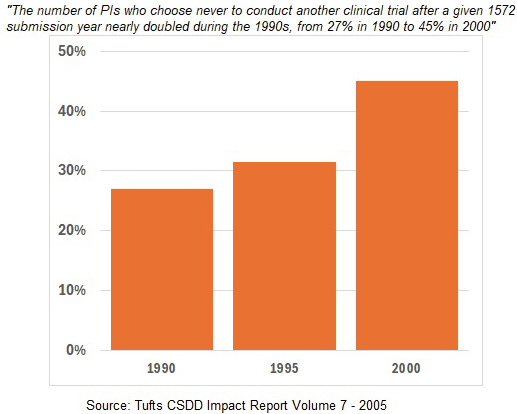

First, this isn’t a looming crisis. People have been writing about it for over 25 years. Here’s a Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD) Impact Report from 2005 that claims high rates of one-and-done PIs stretching back to the 1990s and increasing at a dramatic rate.

And here’s Tufts’ Ken Getz in a 2005 article ominously titled Have We Pushed our PIs Too Far?:

“Turnover rates of clinical investigators are double what they were 10 years ago. Nearly half of all principal investigators will not return to the clinical research enterprise after completing a clinical trial.

…

This tenuous and changing PI landscape poses several major threats to research sponsors and CROs. Declining numbers of investigators and high turnover rates strain the capacity to conduct clinical studies and hinder efforts to establish a well-trained, experienced base of study conduct professionals.”

You may disagree, but to me, it’s a little hard to buy into the story of an industry on the verge of collapse that has apparently also been on that same verge of collapse for three consecutive decades. This may explain why this story seems to ebb and flow a bit. It’s a good one to periodically forget about so that it can be rediscovered and feel fresh in a few years (like when CTTI revived it with “recently published research” back in 2017).

The other problem with our story is: well, it’s probably not, you know, true.

In 2009, Harold Glass suspected something wasn’t quite right with the CSDD data. Specifically, Glass noted that the original analyses were all based on a publicly available FDA database of 1572 Forms. 1572s are required to be completed for every PI in a drug trial, so they seemed a logical source of data about PIs. As Glass pointed out, however, the sponsor just needs to collect the form — submission to the FDA is an optional step. So, the FDA’s database is incomplete — and incomplete in non-measurable ways, since there are no records of who didn’t submit.

Glass did a logical bit of fact-checking: He sent a survey to PIs in the database asking them about their research history. And lo and behold, the PIs who had only one entry in the FDA database reported back that they had a lot more actual trial experience. In the past three years, they reported being an investigator on a median of three Phase 2 or 3 trials. So, the 1572 database was clearly incomplete and generating unhelpful data.

The reaction to Glass’s work was not a reflection of our industry at its finest. We kept the story because the story was better than the facts (you can find many more articles from Tufts updating the analysis, forecasting doom, and ignoring the clear methodological issues). Glass wrote a more pointed article in 2015, noting the misunderstanding around the underlying data, but there appears to have been little to no change in perceptions.

Are there one-and-done investigators? Of course! There are one-and-done everythings. Glass estimated the number wasn’t small, but likely below 20%, which seems reasonable.

But perpetuating the story of huge numbers of disappearing principal investigators and warning of imminent catastrophe, when we know the story is based on a misreading of unreliable data, does nothing to improve clinical research. Let’s let this story go.

About The Author:

About The Author:

Paul Ivsin has been thinking about (and building) clinical trial enrollment programs for over 20 years, supporting both large pharma and biotech companies to run better trials. He is currently the executive vice president of trial engagement services for Continuum Clinical.