Trends In FDA FY2023 Inspection-Based Warning Letters

By Liz Oestreich, Kalah Auchincloss, and Madeleine Giaquinto, Greenleaf Health

The U.S. FDA issued 180 warning letters to drug and biologics manufacturers in fiscal year 2023 (FY23). Of those letters, 94 were based on an on-site inspection of the company, 27 were the result of records requests sent under section 704(a)(4) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), six stemmed from testing product samples, and the remainder were generally based on review of product labels, registration materials, and/or websites.1 This is compared to the 165 drug and biological product warning letters issued in FY22, 74 of which were based on inspections.2 The uptick in the total number of warning letters, as well as the increase in the percentage of inspection-based warning letters (52% in FY23 compared to 45% in FY22) could be the result of a full return to normal inspectional operations after the COVID-19 pandemic. This article provides an analysis of trends and observations from the FY23 inspection-based letters, as well as additional insight on the agency’s approach to enforcement.

Key Statistics

Location

A majority (78) of the inspection-based warning letters were issued to domestic firms in FY23. The remaining 16 were issued to firms in Brazil (1), Canada (1), China (1), Egypt (1), Germany (1), India (7), Mexico (2), Switzerland (1), and Turkey (1).

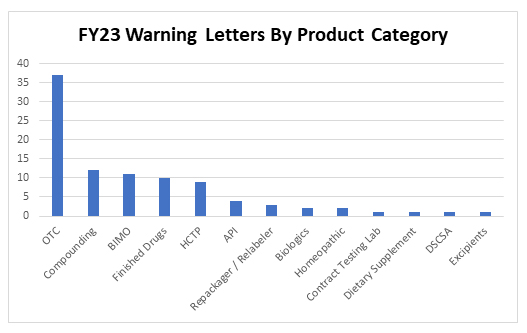

Product Categories

Thirty-seven inspection-based warning letters were issued to over-the-counter drug products in FY23, three of which were indicated for pediatric use. Specifically, letters were issued to companies manufacturing the following types of OTC products:

- hand sanitizer (16)

- unspecified OTC drug (7)

- sunscreen (5)

- nasal spray (3)

- oral use (toothpaste, mouthwash) (3)

- eye drops (1)

- topical pain relief (1)

- antidandruff shampoo (1)

In addition to OTC manufacturers, 12 letters were issued to compounders and 11 letters were issued to clinical investigators or sponsors following inspections conducted as part of FDA’s Bioresearch Monitoring Program (BIMO). Warning letters to manufacturers of products in other categories include: repackagers/relabelers, API manufacturers, producers of human cell and tissue products (HCTPs), and manufacturers of finished pharmaceutical products, biologics, dietary supplements, excipients, and homeopathic products, as well as one letter for a violation of the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) and a letter to a contract testing laboratory.

Top Five Citations

An analysis of citations within the inspection-based warning letters revealed FDA’s top citations for FY2023.

21 CFR 211.100(a)

FDA cited 21 CFR 211.100(a) for failure to establish adequate written procedures for production and process control most frequently: 38 times across the 94 inspection-based warning letters reviewed. This is a common observation, particularly for OTC manufacturers that have not conducted process validation for their products.

21 CFR 211.22

Tied for first place, section 211.22 (failure of quality control to exercise its responsibility to ensure drug products manufactured are in compliance with cGMP) also was cited 38 times. Subsections (a) and (d) of 21 CFR 211.22 were specifically cited by the agency, demonstrating the emphasis the agency has placed on deficiencies in the functionality of quality units. This is again a regulation that has been among the most frequently cited for several years, and it tracks closely to OTC firms, which often have inadequate quality units or none at all.

21 CFR 211.84

FDA cited 21 CFR 211.84 (failure to test and approve or reject components, drug product containers, and closures) a total of 37 times. In particular, the agency frequently cited subsections (d)(1) (failure to conduct at least one test to verify the identity of each component of a drug product) and (d)(2) (failure to validate and establish the reliability of component supplier’s test analyses appropriately), generally together. This regulation has not historically been among the top cGMP violations, but given FDA’s focus on contaminants, it jumped ahead of other regulations in FY23.

In letters citing these regulations, FDA notes, “[c]omponent testing is fundamental to drug product quality” and “[w]ithout adequate testing, you do not have scientific evidence that your incoming components conform to appropriate specifications before use in the manufacture of drug products.”3 Two issues in particular often arose when FDA cited component testing failures: first, where firms failed to perform adequate identity testing of each component lot used in the manufacture of a product and, second, where manufacturers relied on a supplier’s certificate of analysis (COA) without establishing the reliability of the component supplier’s test analyses at appropriate intervals.4

The agency is concerned about potentially hazardous substances that can emerge from adulterated active ingredients. This year, FDA was specifically focused on diethylene glycol (DEG) or ethylene glycol (EG) contamination, stating in multiple warning letters that “[t]he use of ingredients contaminated with DEG or EG has resulted in various lethal poisoning incidents in humans worldwide.”5 In FY23, the WHO issued medical product alerts about contaminated medications, including products indicated for children, found with unacceptable amounts of DEG and EG.6 Contaminated products were associated with more than 300 deaths abroad, many in young children under the age of 5.7 In an effort to protect the public health from this contamination, FDA increased sampling and inspections, updated guidance on DEG, and worked with public health agencies, foreign authorities, and industry to prevent similar outbreaks in the U.S.

21 CFR 211.192

21 CFR 211.192 (failure to thoroughly investigate any unexplained discrepancy or failure of a batch or any of its components to meet any of its specifications whether or not the batch has already been distributed) was cited 30 times. Most of the violations citing this section noted release of product despite the presence of OOS results. In its recommended follow-up, the agency notes: “You do not provide a retrospective review to ensure that you have fully identified and thoroughly investigated all OOS results and discrepancies.”8 This regulation has been one of the most frequently cited violations for many years, demonstrating that industry continues to struggle with implementing effective investigations.

21 C.F.R. 211.165

Finally, the last of the five most frequently cited regulations is 21 CFR 211.165 (failure to test before release for distribution), which was cited 27 times. Similar to 211.100, 211.22, and 211.192, this regulation is frequently in the top five cited violations and tracks with FDA’s continued focus on OTC manufacturers and dangerous contaminants.

Warning Letter Trends

Engaging a Consultant

Standard language in warning letters has continued to evolve over the years. For example, language suggesting retention of a well-qualified consultant has become the norm for most warning letters: 60 of the 94 inspection-based warning letters in FY23 suggested recipients hire cGMP consultants to assist in remediating violations. Over the years, the FDA has become more specific on its consultant recommendations and requests. This year we saw examples of quite detailed requests for which companies should engage a consultant. For example, in the warning letter to Zermat International, the agency strongly recommends that the firm retain a qualified consultant to engage on several specific activities.9 In doing this, the agency effectively gives the company a “to do list” to pass along to the consultant. In Zermat’s case, the consultant requests focus on data integrity (still a topic of significant concern for FDA).

Supply Chain and Shortages

Another emerging section in many warning letters is a note about supply chain resiliency. Specifically, 15 letters included a request that the company provide a warning to the agency when potential shortages may be caused by ongoing remediation efforts. This language coincides with an increased focus on drug shortages over the past year and expanded drug shortage-related authorities enacted as part of the Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act (FDORA) in December 2022.10 The relevant warning letter language states:

“If you are considering an action that is likely to lead to a disruption in the supply of drugs produced at your facility, FDA requests that you contact CDER’s Drug Shortages Staff immediately…so that FDA can work with you on the most effective way to bring your operations into compliance with the law. Contacting the Drug Shortages Staff also allows you to meet any obligations you may have to report discontinuances or interruptions in your drug manufacture under 21 U.S.C. 356C(b). This also allows FDA to consider, as soon as possible, what actions, if any, may be needed to avoid shortages and protect the health of patients who depend on your products.”11

Form-483 Responses

Many warning letters included a section from FDA describing why certain responses to observations in the Form-483 (issued at the close of the inspection) were inadequate. For example, the warning letter to Curexa includes a section on corrective actions, noting that FDA “cannot fully evaluate the adequacy of the following corrective actions described in your [Form-483] response because you did not include sufficient information or supporting documentation.”12 The agency then goes on to list specific observations from the Form-483 with a detailed description of why Curexa’s responses were not sufficient. This language appeared most often in letters to manufacturers of product categories that have historically struggled to meet cGMP requirements, e.g., compounders and developers of HCTPs. This component of the warning letter is useful not only to the recipient of the letter but as an example to other similar manufacturers of what not to do when responding to a Form-483. It may be an attempt by the FDA to educate certain sectors of the industry that are not as sophisticated in cGMPs.

Hand Sanitizers

The public health emergency declared in response to the COVID-19 pandemic ended on May 11, 2023; however, the agency’s response to COVID-era products persists. In FY23, the FDA sustained its focus on OTC products overall, with a continued specific focus on hand sanitizers. The FDA began to identify safety concerns with hand sanitizers in the spring of 2020, including hand sanitizers contaminated with methanol, a substance that can be toxic when absorbed through the skin and deadly when accidentally ingested. The 16 inspection-based warning letters sent to hand sanitizer manufacturers underscore FDA’s ongoing focus on the safety of this widely used product, even as the demand for hand sanitizer has decreased.13

Notably, in FY23, FDA inspected and issued a warning letter to an ethanol API supplier stating concerns surrounding hand sanitizer and explicitly noting that “[t]he use of ethanol contaminated with methanol has resulted in various lethal poisoning incidents in humans worldwide.14 This may have been an effort by FDA to prevent contamination of finished hand sanitizer by holding ethanol suppliers accountable for the quality of their API.

FDA also cited several hand sanitizer manufacturers for failing to separate products such as industrial chemicals from hand sanitizer for human use.15 Cross-contamination from dual-use manufacturing facilities and failure to test incoming components are the most frequently cited violations in warning letters to OTC hand sanitizer producers. These violations may be a consequence of COVID-era policies that encouraged nontraditional drug manufacturers to enter the hand sanitizer market to meet increasing demand during the pandemic. These firms are not familiar with cGMPs but have continued to linger in the market.

Contract Manufacturers

As a follow-up to our FY22 observations, we note FDA’s continued focus on the role of contract manufacturers. Similar to the 18 letters issued in FY22, FDA underscored the responsibilities of both the contract manufacturer(s) and the product sponsor in 19 letters in FY23. FDA repeatedly notes that contract manufacturers are subject to cGMPs and quality requirements, just like other manufacturers, but that the product sponsor is ultimately responsible for the finished product and has a duty to oversee its contractors and suppliers. For example, in several warning letters the agency articulates that:

“Drugs must be manufactured in conformance with cGMP. FDA is aware that many drug manufacturers use independent contractors such as production facilities, testing laboratories, packagers, and labelers. FDA regards contractors as extensions of the manufacturer.”16

Records Requests

In addition to the inspection-based warning letters, the agency utilized its authority under 704(a)(4) to compel companies to share information in advance of or in lieu of an on-site inspection. FDA began using records requests in earnest during the COVID-19 pandemic when on-site inspections were temporarily paused and then severely limited for several years. The 704(a)(4) authority was expanded at the end of 2022 in FDORA in notable ways, emphasizing the importance of this tool even as on-site inspections are ramped back up post-pandemic.17 In FY23, there were 27 warning letters issued to firms based on 704(a)(4) requests. Of those 27, 12 cited the firm for refusal to provide access to records. The remaining 15 firms responded to the document request and received warning letters based on their (inadequate) responses. Notably, of the 27 warning letters based on 704(a)(4) requests, 16 were issued to facilities in foreign countries.

Emerging Areas of Focus

As the implementation of the DSCSA moves forward, the agency is beginning to enforce against companies that have not built systems to identify and trace drug products at the package level. Section 582 of the FD&C Act includes requirements for certain entities along the pharmaceutical supply chain (including wholesale distributors) related to product tracing, serialization, verification, and trading partner authorization. Safe Chain Solutions, LLC, a wholesale drug distributer, received the second warning letter ever issued18 for DSCSA violations tied to repeated distribution of counterfeit HIV antiviral drugs.19 In its letter to Safe Chain, FDA cited the company for shortcomings of its internal systems and processes related to DSCSA requirements, i.e., not having adequate verification systems in place and failing to maintain records regarding suspect product investigations. Additionally, Safe Chain was cited for its failure to respond to an external notification of illegitimate product, which is a key underlying function of the law. FDA’s goal in leveraging the DSCSA requirements is to ensure prompt identification and removal of illegitimate or adulterated products from the supply chain, which necessitates coordinated investigations and communication between trading partners (i.e., a firm’s tracking and tracing obligations extend beyond its internal verification systems). Safe Chain also was found to have engaged in transactions with unauthorized trading partners, a serious concern given the high-risk nature of the fake HIV products that were being introduced by these unlicensed entities.20

Although the FDA extended its final enforcement deadline for enhanced drug distribution requirements in November of 2023 for a one-year stabilization period,21 the agency will undoubtedly continue to be focused on ensuring compliance with track and trace requirements that have already come into effect, in addition to continued progress toward full implementation.

Conclusion

The number of inspection-based warning letters increased in FY23, as compared to FY22, likely as a result of FDA’s steady increase in the number of inspections it conducts since the initial pandemic-related shutdown in March 2020. The most frequently cited cGMP violations in the inspection-based warning letters were consistent with past years, with the exception of cGMP regulations related to component testing, which jumped into the top five most frequent citations this year. Other trends, similar to past years, include continued focus on OTC products generally, and hand sanitizers specifically, a heavy domestic concentration of warning letters, and common language related to engaging consultants and contractor responsibilities. Newer trends are also emerging, including attention to drug shortages, detailed references to inadequate Form-483 responses, and DSCSA violations. The FDA also continues to use its 704(a)(4) records request authority, which we do not expect to slow down.

References/Notes

- Data was pulled from FDA’s Warning Letter Database on Jan. 24, 2024, and updated Feb. 2, 2024.

- Trends in FY22 Inspection-Based Warning Letters, K. Auchincloss, M. Giaquinto, L. Oestreich, Feb. 21, 2023, https://www.outsourcedpharma.com/doc/trends-in-fda-fy-inspection-based-warning-letters-0001

- Warning Letter to Formology Lab Inc., March 1, 2023.

- Warning Letter to Fuller Industries Inc., June 28, 2023.

- [1] Warning Letter to LCC Ltd., Aug. 3, 2023.

- [1] Presentation by Jill Furman, Director, Office of Compliance, CDER, FDA at the FDLI Enforcement Conference, December 2023.

- Id.

- Warning Letter to Zermat International, S.A. de C.V., April 6, 2023.

- Warning Letter to Zermat International, S.A. de C.V., April 6, 2023.

- Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022 (FDORA), part of the larger Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 (Public Law 117-328).

- Warning Letter to Centrient Pharmaceuticals India Private Limited, Dec. 7, 2022.

- Warning Letter to Curexa East dba Curexa, Sept. 13, 2023

- In addition to warning letters to hand sanitizer manufacturers after an on-site inspection, FDA also issued several letters to hand sanitizer manufacturers based on sample testing. The number of testing-based warning letters has decreased since the end of the pandemic public health emergency, but testing and sampling is still a viable basis for a warning letter and a regulatory tool available to FDA.

- Warning Letter to Pharmaplast SAE, April 13, 2023. FDA placed firm on Import Alert 66-40 on April 4, 2023.

- Warning Letter to AG Hair Limited, Nov. 28, 2022.

- Warning Letter to Premier Nutra Phama, Inc., Dec. 9, 2022, and Warning Letter to Atlantic Management Resources dba Claire Ellen Products, Jan. 20, 2023.

- Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022 (FDORA), part of the larger Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 (Public Law 117-328).

- The first DSCSA-related warning letter was issued to McKesson Corporation, another wholesale distributer, back in 2019. See FDA Warning Letter to McKesson Corporation Headquarters, February 2019, available at https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/mckesson-corporation-headquarters-2719-565854-02072019.

- Warning Letter to Safe Chain Solutions, June 8, 2023.

- For more information about the Safe Chain warning letter, see “FDA Issues Second DSCSA Warning Letter – What Does This Mean?” available at https://www.outsourcedpharma.com/doc/fda-issues-second-dscsa-warning-letter-what-does-this-mean-0001#:~:text=The%20second%20warning%20letter%20violation,to%20verify%20that%20all%20trading.

About The Authors

Liz Oestreich, J.D., is senior vice president of regulatory compliance at Greenleaf Health. She brings more than nine years of regulatory experience and a diverse background of legal, public policy, and non-profit sector knowledge to her position. As a consultant, Oestreich provides strategic guidance on premarket and postmarket issues to drug, medical device, tobacco, and cannabis companies. She earned her J.D. from the University of the District of Columbia, David A. Clarke School of Law, and her B.A. from the University of Arizona.

Kalah Auchincloss, J.D., M.P.H., is executive vice president of regulatory compliance and deputy general counsel for Greenleaf Health. She has more than 15 years of food and drug legal, policy, and regulatory experience at the FDA, on Capitol Hill, and in the private sector. At Greenleaf, Auchincloss advises pharmaceutical and medical device companies on compliance, policy, and other regulatory issues. Before moving to Greenleaf, Auchincloss spent six years at the FDA in the Commissioner’s Office and in CDER’s Office of Compliance and Office of Regulatory Policy. She earned her J.D. from Georgetown University, her M.P.H. from Harvard University, and her B.A. from Williams College.

Madeleine Giaquinto is director of regulatory affairs at Greenleaf Health, an FDA regulatory consulting company based in Washington, DC. She provides clients with timely analysis of FDA regulations, policies, and guidance documents related to good practice standards for all FDA-regulated medical products. She also advises clients on strategic engagement with the FDA on a range of policy and compliance-focused matters. Giaquinto’s public health policy and regulatory compliance expertise stem from her 9+ years working across legal, government/legislative affairs, and hospital administrative settings. She has a J.D. from George Mason University and a B.S. in biology from Georgetown University.