4 Ways To Listen Like A Linguist — And Improve Trial Inclusion

By Kathryn Ticknor, senior research manager, Inspire

Practical discussions around inclusion often go something like this:

A sponsor is interested in anticipating potential barriers to enrollment based on a newly drafted protocol.

“Let’s show the protocol to patients and see what they think,” suggests a patient engagement advocate.

“Well, I don’t know. We’d have to speak to so many people. And the data could get messy,” the sponsor replies.

From an analytical perspective, “messy” data refers to anything qualitative, ethnographic, or linguistic in nature. These methods often involve smaller sample sizes, placing trust in the hands of an experienced researcher. And in some cases, what’s most messy is relinquishing full control over the questions asked and taking an inductive, rather than deductive, approach.

While commercial research teams have long leveraged qualitative methods to better understand patients and providers within consumer markets, R&D has been more hesitant. Even when patients and communities are engaged, we often design engagements around surveys, with a focus on larger sample sizes, easily quantifiable data, and little room for subjective interpretation. However, avoiding messy data can prevent us from uncovering the most actionable insights.

The Linguistic Toolkit

Linguists working in medical research provide a scientific lens from which to analyze how patients think about, talk about, and live with a given condition, symptom, or treatment. Importantly, they are also responsible for translating those findings into recommendations for how sponsors can develop products, design trials, and use patient-facing communications.

By listening like a linguist, even those new to qualitative techniques can leverage the rewards of stepping outside of their methodological safety zone. Listening like a linguist involves asking the right questions and synthesizing patterns of meaning from the answers provided.

So how, exactly, does one listen like a linguist?

1. Let patients drive the conversation.

First and foremost, listening like a linguist means putting the respondent in control of the dialogue, trusting them to guide the conversation to what is most salient to their own experience. In our example of eliciting feedback on a drafted protocol, patients may surprise designers by having less input on a dosing frequency than on a required blood test — listening means avoiding assumptions about what will be most important to a given group. While developing a discussion guide is helpful for consistency when speaking with multiple participants, a linguist isn’t afraid to follow up on an answer that hints at an underlying motivation, concern, or unmet need. Unlike in quantitative research, qualitative methods give us the ability to employ dynamic, open-ended questions about respondents’ experiences. Further, it gives patients a chance to provide feedback using a more natural narrative framework: providing background and explaining why, where needed.

Linguists are also well trained to hear words with shades of meaning. While health literacy advocates suggest avoiding medical jargon, it is often difficult to identify how certain terms will resonate with patients until these terms are put in context. For example, engaging patients with drafted protocols can identify if unnecessary hedging (e.g., mitigated phrasing such as “thought to work”) in descriptions of a drug’s mechanism of action reduced patient confidence in the drug’s efficacy. Terms often thought to be well understood by a general audience (e.g. randomization, standard of care) are revealed to have a variety of connotations among different patient populations.

2. Listen for what isn’t said.

Listening like a linguist will involve returning the data – in this case, the natural language used by respondents to describe their experiences, ask questions, voice concerns, and provide feedback — to synthesize clear patterns of meaning. In addition to the common themes voiced throughout the data, a linguist recognizes that what is not talked about, or expressly avoided, is just as revealing about the respondent’s perceptions as what is said.1 These “noisy silences” can speak volumes about a patient’s priorities and expectations.

One of the benefits of incorporating an inductive approach is the ability to ask, “What should I be asking you that I haven’t?” If a patient must be prompted to discuss whether transportation is a barrier to enrollment, is transportation a non-issue or has it never occurred to the patient that help could be available to assist with transportation?

3. Listen to stakeholders outside your immediate audience.

Even in the commercial and post-market space, patient engagement initiatives can often become siloed strictly on engaging only those patients who represent the patient profile of interest. While it is important to listen to the perspective of those we are seeking to enroll in any given trial, include the voices of caregivers, acknowledging the valuable and unique insights they can contribute.

This is particularly important when exploring topics that may involve a sensitive or taboo discussion topic, or when a patient may have difficulty articulating unmet needs that are more recognizable to family and community members. Engage stakeholders and the community from multiple perspectives and angles.

For example, caregivers are often able to provide deep insights regarding the impact of trial participation on childcare and household management, as well as concerns a patient may have regarding impacts on sexual health or alcohol consumption.

4. It’s never too early (or too late) to start listening.

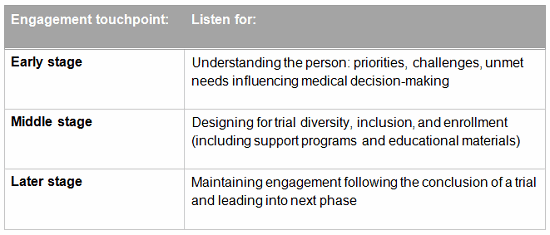

While listening early to patient needs is crucial, a linguistic approach recognizes that it’s never too late to incorporate the patient perspective. Asking questions aimed at improving the design and outcomes of a trial are important, but inclusion can also be improved by incorporating the patient voice across all phases of research and development:

Qualitative interviewing with a linguistic focus was recently used to evaluate educational materials being developed for a rare disease. The objective was to assess how well the language in the materials resonated with the way these patients naturally described their own symptoms and condition. Analysis showed that a phrase in the brochure was potentially face-threatening, because it implied that their disease had left them socially isolated. The passage was reframed to avoid an implication that did not resonate or reflect the lived experience of the population.

Conclusion

Discerning meaningful communication patterns out of “messy” data can be a challenge — but an incredibly worthwhile endeavor. These qualitative methods can also inform and complement quantitative research, validating insights, providing emotional depth, and explaining why. By applying robust market research methodologies and techniques, we can better understand and engage with diverse participant needs and identify population-specific barriers to participation in clinical trials.

References:

- Charlotte Linde, Working the Past: Narrative and Institutional Memory, Oxford University Press, December 2008.

About The Author:

About The Author:

Kathryn Ticknor is senior research manager at Inspire. As a health communications and medical marketing researcher, she draws on expertise in linguistic insights, ethnography, and human-centered design. Motivated by her own family's experience with chronic illness, she has focused her work on in-depth, disease-state specific research supporting partners across the healthcare space.