2 Ways To Make Eligibility Checklists More Meaningful

By Kamila Novak, KAN Consulting

An eligibility assessment of screened participants is one of the three key activities — the other two being safety evaluations and adherence to the allocated therapy — that ensure the data collected and analyzed can be used for sponsors’ and regulatory decision-making. If participants are enrolled in violation of these eligibility criteria, they are exposed to unknown risks, and the sponsor’s statistical analyses can be derailed since we have apples, oranges, and peaches in one bucket, i.e., nonhomogeneous populations different from those defined in the study protocol.

The whole purpose of the eligibility assessment is to ensure the right population, per protocol, passes screening and receives the study therapy. Yet, in almost every study, we find participants who did not meet eligibility criteria at the time of randomization. The misstep may be discovered shortly after randomization, during their treatment, or even at or after the end of the study. Yet in every study, site personnel are trained on the study protocol, and monitors collect corresponding training records. So why do ineligible participants make it into a study? There is a plethora of questions to ask (and answers to consider). For example:

- Are the eligibility criteria clear and unambiguous?

- Are the criteria too numerous and overwhelming?

- Does the population defined by our eligibility criteria exist?

- Can we be reasonably sure all sites understand them?

- Is there a high site staff turnover? Who and when trained the new personnel?

- Are the people performing eligibility assessments qualified to do so?

- Do principal investigators oversee delegated activities?

- Are the criteria listed in the case report form (CRF) as a reminder? Or, is there just a question “Is the participant eligible?” with a yes/no answer option?

- Is the typical procedure of eligibility assessment fit for purpose?

Although each of these examples or a combination of them can reveal the cause of the trouble, I would like to focus on the last one since virtually the same checklist format is used in all conducted studies.

The Hidden Trap Of Eligibility Checklists

To document eligibility assessments conducted by investigators, the sponsors or their CROs use study-specific eligibility checklists. These checklists are populated in the CRFs and filed as worksheets in the study sites’ source documents. Some sites produce their checklists, however, they tend to do it the same way they have learned from sponsors.

What am I talking about? Study protocols list all inclusion criteria under one heading and all exclusion criteria under another heading in the Patient Population chapter. That makes sense. However, if we copy/paste them as they are when we develop the eligibility checklist, we get a format that poses the risk of mechanical completion, which undermines the very purpose of the assessment.

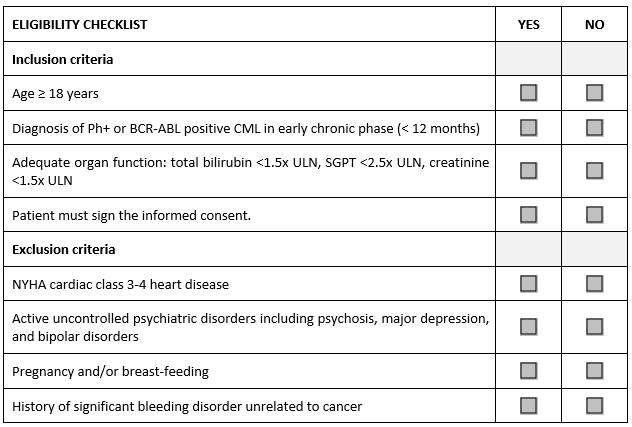

Consider the abbreviated sample checklist from a Phase 2 study in patients with an early phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) that illustrates the problem.

Have you seen or do you use something like this in your studies? As an auditor, I find it in every CRF and every worksheet. How is it completed by study personnel? They tick “yes” for every inclusion and “no” for every exclusion criterion without reading the criterion text. It takes no time at all. Investigators and their teams are remarkably busy people, and they genuinely believe they know their patients very well. Whether they remember the nuances of each study protocol is another question. The eligibility assessment has become a check-box exercise.

Can we do something about it? Yes, we can and should. I intentionally omit resource-intensive options, such as disabling randomization, until all screening data are reviewed by medical or clinical monitors. This would require an army of medical monitors working 24/7 during the whole recruitment period, and their access to source documents, which would create additional work for the sites if their source documents are paper-based or hybrid, cause delays, and overall, be operationally challenging.

Improvement Option One

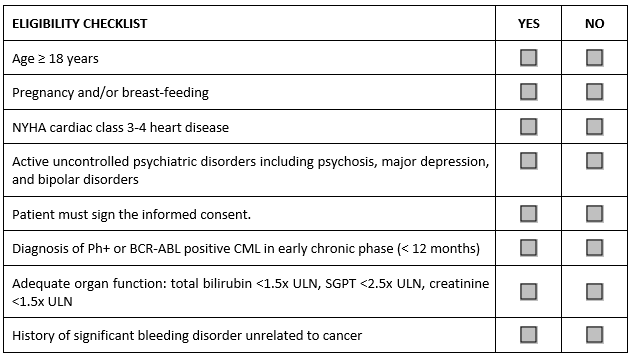

This solution is a low-hanging fruit that costs nothing. We can simply mix and mingle both inclusion and exclusion criteria under one eligibility heading. The result looks like this:

To answer it correctly, the investigator or designee completing this checklist needs to read each criterion to see if it means an inclusion or an exclusion. Electronic CRFs can be programmed with minimum effort to randomly shuffle the order of criteria, so the eligibility checklist will be different for each patient. Easy and quite effective, the mechanical completion is eliminated.

Improvement Option Two

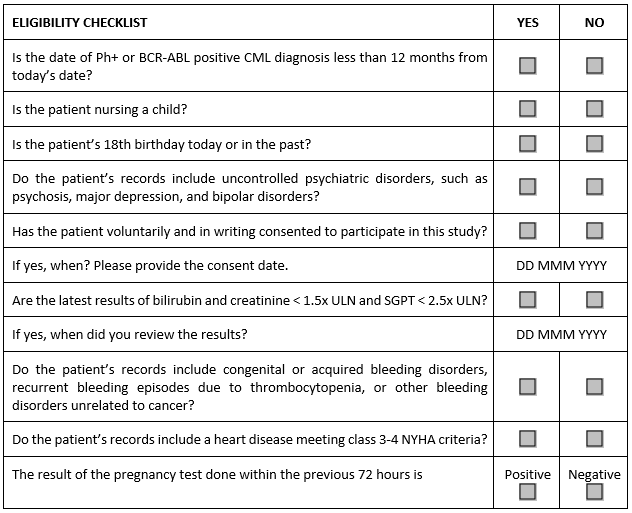

The assessment can be made truly meaningful by rephrasing each criterion in such a way that the investigator performing the assessment will need to review at least part of the participant’s medical records to answer questions representing individual criteria. In our sample study, the checklist for this option may look like this:

This option requires effort to articulate the right questions and have them reviewed by the study physician or medical monitor — and it is also likely to prompt an outcry at the study sites since it creates more work for their staff. On the sponsor or CRO side, the process can be made more efficient by collecting a bank of reviewed and approved questions that can be used across studies. Since many criteria are the same, the time to develop study-specific checklists can be reduced.

Conclusion

The ICH E6 guideline on Good Clinical Practice and derived regulations mandate everyone involved in medicinal product development must ensure participants’ safety and well-being. Nevertheless, enrollment of ineligible participants remains a significant source of noncompliance reported by auditors and inspectors.

Since eligibility assessment is part of critical processes in clinical trials and current practices seem to be suboptimal, we need to design process improvements and effectively manage change. Solutions presented in this article may become a catalyst for designing changes leading to such improvements. As with every change, sponsors, and CROs should evaluate the effectiveness of various solutions in pilot projects before any large-scale implementation.

About The Author:

Kamila Novak, MSc, has been involved in clinical research since 1995, having worked in various positions in pharma and CROs. Since 2010, she has run her consulting company, focusing mostly on GXP auditing. She has first-hand experience with countries in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and North America. Kamila Novak chairs the DIA Clinical Research Community and the SQA Beyond Compliance Specialty Section, leads the DIA Working Group on System Validation, serves as a mentor at the SQA and the DIA MW Community. In addition, Kamila is a member of the CDISC, the European Medical Writers’ Association, the Florence Healthcare Site Enablement League, the Continuing Professional Development UK, the Association for GXP Excellence, and the Rare Disease Foundation. She publishes articles and speaks at webinars and conferences. She received the SQA Distinguished Speaker Award in 2023 and 2024, and the DIA Global Inspire Award for Community Engagement in 2024. She and her company actively support capacity-building programs in Africa.

Kamila Novak, MSc, has been involved in clinical research since 1995, having worked in various positions in pharma and CROs. Since 2010, she has run her consulting company, focusing mostly on GXP auditing. She has first-hand experience with countries in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and North America. Kamila Novak chairs the DIA Clinical Research Community and the SQA Beyond Compliance Specialty Section, leads the DIA Working Group on System Validation, serves as a mentor at the SQA and the DIA MW Community. In addition, Kamila is a member of the CDISC, the European Medical Writers’ Association, the Florence Healthcare Site Enablement League, the Continuing Professional Development UK, the Association for GXP Excellence, and the Rare Disease Foundation. She publishes articles and speaks at webinars and conferences. She received the SQA Distinguished Speaker Award in 2023 and 2024, and the DIA Global Inspire Award for Community Engagement in 2024. She and her company actively support capacity-building programs in Africa.