What Does It Mean To Be "Underserved"?

By Jessica Cordes, consultant, Clinical Excellence GmbH

Clinical research professionals have long understood the disparities in clinical research access and outcomes among diverse populations. In talking about those groups, various identifiers and terms have been used: unrepresented, underserved, and marginalized, to name a few. But when we use them, what do we mean exactly?

In 2017, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research Clinical Research Network (NIHR CRN) launched the INCLUDE Project (Innovations in Clinical Trial Design and Delivery for the Under-served) and concluded it in 2021. The project aimed to enhance clinical research inclusivity by developing the NIHR-INCLUDE Framework and Guidance through a co-design process involving diverse stakeholders.

In part, the research identified populations who were most commonly excluded from clinical trials and identified the term “underserved” as the most suitable descriptor, because it emphasizes the research community's responsibility to better serve these groups. Based on that report, this article aims to define “underserved” groups, explore the importance of their participation in research, discuss the barriers to doing so, and offer ways to improve their inclusion.

Understanding Underserved Groups

The INCLUDE Project was one of several major projects in innovation. Commissioned by the NIHR CRN in 2017, it aimed to improve health research inclusivity. The project concluded at the end of 2021.

The NIHR-INCLUDE Framework and Guidance were developed through a co-design process to ensure their suitability. The project involved engaging with a diverse range of stakeholders across the research life cycle, which helped in reaching the necessary audiences for NIHR-INCLUDE to promote inclusivity in health and care research.

The NIHR-INCLUDE project identified “underserved” as the most suitable term through a consensus workshop with diverse stakeholders. Adopted by the NIHR, this term emphasizes that the research community must better serve these groups, highlighting that their lack of inclusion is not their fault. Unlike “underrepresented,” underserved underscores this perspective.

The NIHR-INCLUDE project demonstrates that there is no universal definition for an underserved group. However, certain key characteristics are commonly observed among several under-served groups:

- Lower research inclusion than population estimates suggest

- Significant healthcare burden with insufficient research focus

- Differences in how the group responds to or engages with healthcare interventions compared to other groups, with research often not addressing these factors

The central concept is that the definition of underserved is highly context-specific; it depends on the population in question, the condition being studied, the research questions posed, and the intervention being tested. Therefore, a singular and simple definition cannot encompass all underserved groups.

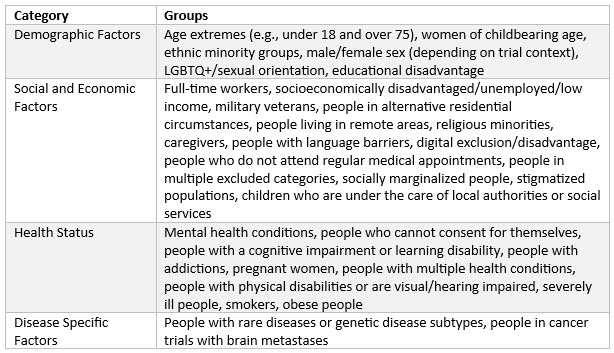

Examples Of Underserved Groups

An important conclusion from the research is that the definition of underserved is often highly context-dependent and specific to the study in question. A group considered underserved for one disease or type of research may not be the same for another. The following are examples derived from surveys, stakeholder group discussions, and a literature review conducted during the NIHR-INCLUDE project. This list is not exhaustive but aims to illustrate groups that may be underserved in certain contexts or more broadly within the research landscape.

Importance Of Inclusion In Clinical Research

It is important to include underserved groups in health and care research for various reasons.

- The omission of a diverse range of participants may result in findings that are not generalizable to a wider population.

- Groups may react differently to an intervention due to physiological or disease state differences. Studying various groups ensures a favorable risk-benefit balance for each group.

- Without evidence of an intervention's effect on a specific group, clinicians may hesitate to offer it, relying on clinical opinion instead.

- Delivering interventions to target populations involves complex factors, including logistical, sociocultural, psychological, and biological differences. Without testing the deployment of an intervention across diverse groups, its practical effectiveness cannot be confirmed.

The principle of “no decision about me, without me” advocates for the inclusion of underserved groups in research. To enable clinicians and patients to make well-informed decisions, the evidence base must be established through the participation of a diverse range of groups in the supporting research.

Barriers To Inclusion

Here are examples from surveys, stakeholder discussions, and literature reviewed in the NIHR-INCLUDE project. This list is not exhaustive but provides a general idea of the barrier categories encountered.

It is essential to identify specific barriers associated with individual projects, communities, and disease areas when implementing tailored solutions to ensure the inclusion of underserved groups in a context-specific manner:

- Physical disability barriers

- Difficulties consenting for others

- Feeling unqualified (e.g., lack of education)

- Lack of available trials/poor promotion

- Ineffective incentives for participation

- Disinterest in research

- Distrust in research

- Negative attitudes toward research

- Financial impact

- Denial of health condition

- Poor consent procedures

- Additional caregiver time required

- Perceived participant risk

- Cultural barriers

- Health fears (e.g., hospitals, needles)

- Research-unfriendly treatment centers

- Excessive trial demands

Strategies For Improving Inclusion

The following aspects should be assessed when preparing the diversity plan:

- The characteristics and demographics of the population that your research looks to serve should be clearly identified.

- Your inclusion and exclusion criteria should enable your trial population to match the population that you aim to serve.

- Any differences between your projected trial population and the population you aim to serve should be justified.

- Your recruitment and retention methods should engage with underserved groups effectively.

- There should be evidence that your intervention is feasible and accessible to a broad range of patients in the populations that your research seeks to serve.

- Your outcomes should be validated and relevant to a broad range of patients in the populations that your research seeks to serve.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the promotion of diversity in clinical trials is not only a matter of ethical research practice but also essential for the generalizability and applicability of research findings. By ensuring that trial populations accurately reflect the diverse characteristics and needs of the broader population, researchers can enhance the relevance and effectiveness of their interventions.

Implementing a robust diversity plan requires careful consideration and strategic action across all stages of the research process. It involves identifying the target population, setting inclusive criteria, engaging underserved groups, and ensuring the feasibility and accessibility of interventions. Furthermore, validated and relevant outcomes must be established to ensure that the benefits of research are equitably distributed.

Ultimately, fostering inclusivity in clinical research will lead to more comprehensive and impactful health outcomes, benefiting society as a whole. Researchers and stakeholders must remain committed to these principles to drive meaningful progress in the field of clinical research.

References:

Ensuring that COVID-19 research is inclusive: guidance from the NIHR-INCLUDE project

About The Expert:

Jessica Cordes started her clinical operations career in 2009, working at various companies including Big Pharma and several small to midsize biotech companies. She gained extensive experience on different levels from country study management to global study management and, since 2018, leadership in clinical operations. During her time at Medigene and Immatics, she structured the clinical operations department, built cohesive global teams, and implemented GCP and ATMP-compliant processes. For more than 12 years, she has been working in oncology clinical trials (including hemato-oncology as well as solid tumors) and with ATMPs since 2018. Since 2023, she has been working as an independent consultant and trainer, supporting small companies in building their clinical operations group and setting up their clinical trials for success. She provides a GCP refresher course via her Clinical Excellence Training Academy.

Jessica Cordes started her clinical operations career in 2009, working at various companies including Big Pharma and several small to midsize biotech companies. She gained extensive experience on different levels from country study management to global study management and, since 2018, leadership in clinical operations. During her time at Medigene and Immatics, she structured the clinical operations department, built cohesive global teams, and implemented GCP and ATMP-compliant processes. For more than 12 years, she has been working in oncology clinical trials (including hemato-oncology as well as solid tumors) and with ATMPs since 2018. Since 2023, she has been working as an independent consultant and trainer, supporting small companies in building their clinical operations group and setting up their clinical trials for success. She provides a GCP refresher course via her Clinical Excellence Training Academy.