When AI Meets Accounting: AI Costs And Intangible Asset Treatment For Sponsors And CROs

By Jennifer Dzierzak and Karen McDaniel, Crowe

As sponsors and CROs increasingly integrate AI into clinical trials, data management, and analytics, finance leaders across both organizations face a pressing challenge: how to account for AI-related costs under evolving U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

The life sciences ecosystem is focused not only on deploying AI effectively but also on mitigating risks and exposures, such as identifying hallucinations and verifying the reliability of AI data, output, and processes. The types of AI technologies used vary across different departments and at different stages of the contract life cycle. Sponsors and CROs using AI should be aware of some of the common use cases for currently emerging AI, understand how financial reporting treatment can differ due to complexities in the accounting rules and the related impacts, and be clear on what finance professionals should be thinking about as they embark on the AI journey.

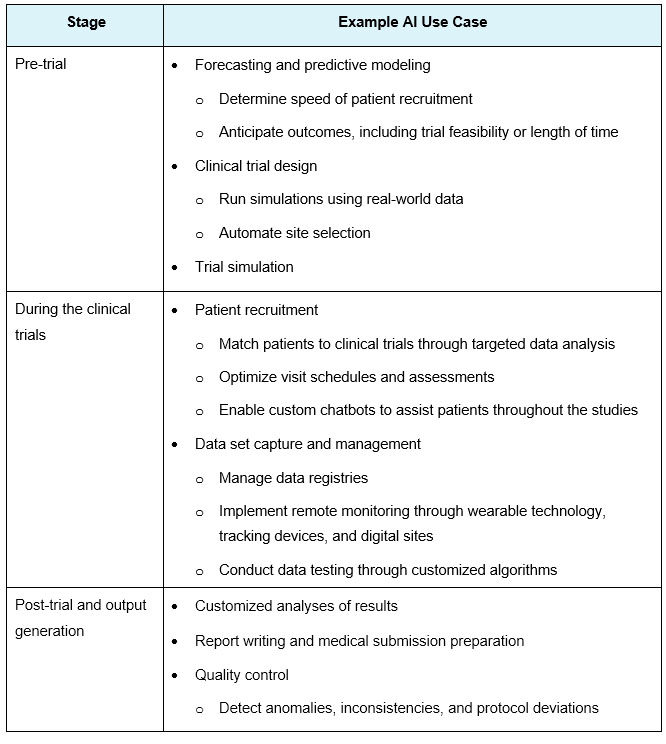

AI Use Cases

Life sciences organizations have ample opportunities to use AI throughout the clinical trial life cycle. Some of the potential use cases are shown in the following table.

Financial Reporting Considerations

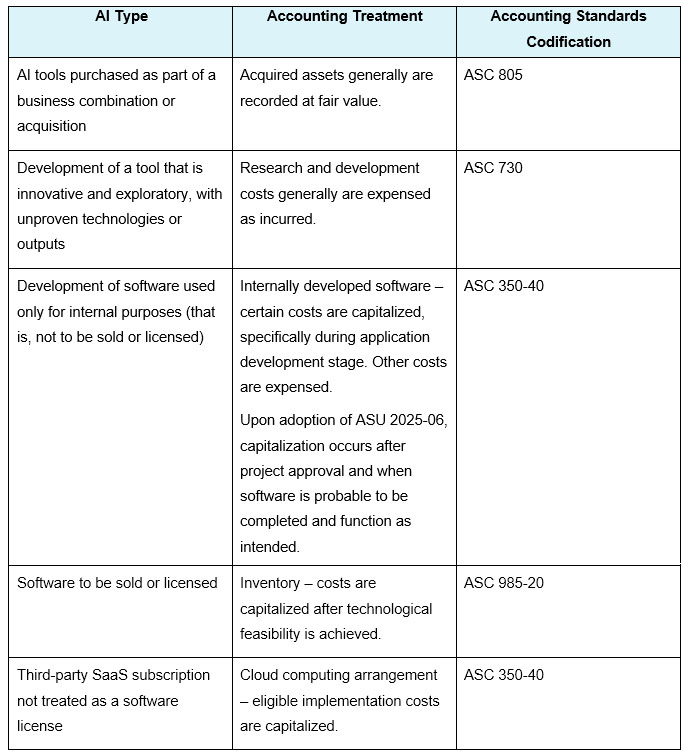

Uses of AI throughout the clinical trial life cycle vary, and the costs incurred for developing or implementing such technologies are capitalized as an asset or expensed immediately based on several factors.

One key consideration for software is its intended use – whether it will be sold as a product or service or used internally for service delivery. If the software is sold, leased, or otherwise marketed commercially, the accounting follows Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 985, which requires the software to be technologically feasible before related costs can be capitalized as an asset. If the software is for internal use or service delivery, certain AI-related costs – such as coding and direct implementation expenses – can be capitalized during the application development stage, continuing until the software is ready for its intended use.

Additionally, tools that begin as internal-use applications later might be offered externally once measurable business value is achieved. This evolution further complicates accounting treatment, particularly with respect to reclassification and capitalization when transitioning between ASC 350-40 and ASC 985-20. Such outcomes are common in AI development, where projects often progress in an evolving environment without a clearly defined end state.

AI assets also differ from traditional software in that they might deteriorate more quickly due to factors such as model drift, outdated training data, and evolving regulatory requirements, increasing the risk of impairment. In addition, AI tools often require ongoing evaluations, guardrails, and monitoring for issues such as hallucinations, all of which demand additional development time and resources. As a result, the distinction between development and maintenance activities can become blurred, making appropriate accounting treatment more complex.

Determining whether the costs incurred relate to software, another type of intangible (such as a process or database), or something else entirely also requires careful judgment. Depending on the nature of the activity, costs may fall under research and development costs, which generally are expensed as incurred under ASC 730. Similarly, most costs incurred for internally developed intangibles are expensed as incurred unless specific rules governing capitalization – such as for software or assets acquired in a business combination – apply.

Impact Of Accounting Standards Change

Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2025-06, issued in September 2025, updates the internal-use software guidance. It becomes effective for fiscal years ending after Dec. 15, 2027, with early adoption permitted. The types of costs that may be capitalized remain largely the same; however, the update removes the project stage capitalization framework and replaces it with two criteria: 1) management approval to complete the project and 2) a probability that the software will be completed and used as intended. The level of cost capitalization achieved under the revised guidance can vary significantly depending on the level of development uncertainty involved with the project. Additionally, traditional software capitalization timelines don’t always map cleanly to AI, and under the “probable completion and use” criteria, it’s unclear how to account for work that’s continually in process.

The following table highlights potential accounting implications for different types of AI tools.

Financial Statement Impacts

Proper cost treatment directly shapes how a company’s financial position and performance are reported under GAAP and non-GAAP measures. Determining whether a cost should be expensed or capitalized might require judgment to comply with applicable accounting standards – it is not an accounting policy election or preference.

Expensing costs records them immediately as operating expenses, increasing current period costs and reducing current period net income and operating income. Capitalizing costs records them as assets, avoiding an immediate impact to earnings; the cost instead is recognized gradually through depreciation or amortization, resulting in higher current period net income than when costs are immediately expensed.

This distinction also affects earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). To the extent an item is capitalized as an intangible asset, it flows through EBITDA as an amortization addback at the time the cost is expensed through earnings; therefore, capitalizing AI-related costs typically has a net-zero impact on EBITDA. In contrast, immediate expensing of costs reduces EBITDA in the year it occurs. As a result, companies might appear to have stronger current operating performance under a capitalization model, even though cash outflows are unchanged.

Cost classification also influences debt covenant compliance, especially when covenants are tied to operating income or EBITDA. Expensing through operations reduces earnings and EBITDA in the year incurred, which might risk noncompliance of covenants, while capitalization is EBITDA neutral, thus positively affecting covenant ratios.

In summary, the judgment applied in determining the type of asset and use, which affects the ability to capitalize or expense the AI and other related costs, can have an impact on financial performance metrics, investor perception, and covenant compliance, underscoring the importance of accurate and standards-aligned cost classification.

Financial Reporting For AI

To ensure accuracy in accounting for AI, finance leaders must understand AI’s place within the organization, including the purpose of the technology, its intended use, and the costs involved. Once an AI project is defined, leaders should take the following steps.

- Understand which accounting model applies and whether the expenditure is treated as an asset or an expense.

- For internal-use software under ASC 350-40, determine when to apply the guidance of ASU 2025-06. Will the guidance be early adopted, or will the company wait until adoption is required (fiscal years beginning after Dec. 15, 2027)?

- If ASU 2025-06 is early adopted, determine when the new capitalization threshold will be met (management authorization plus probable completion and use). Judgment might be needed to assess whether “significant development uncertainty” exists.

- Maintain contemporaneous documentation.

Preserve key project records, such as feasibility assessments, design approvals, meeting notes, and milestone review signoffs, to support capitalization decisions.

- Track internal and third-party costs accurately.

Accurate cost records and allocation are essential for determining which expenses qualify for capitalization.

- Implement time tracking systems that allocate effort by project. Develop an internal cost allocation policy for AI projects with guidance for shared full-time equivalents and blended project work.

- Use cost codes that distinguish between capitalizable and noncapitalizable tasks.

- Require vendors to specify the nature, scope, and timeline of deliverables in statements of work.

- Support useful life and amortization estimates with evidence.

Document the rationale for useful life estimates, including considerations for technological obsolescence, model performance degradation, and expected duration of utility. Significant judgment might be required.

- Monitor for impairment indicators.

Establish procedures to assess whether capitalized AI assets are still in use, continue to generate intended economic benefit, or have become obsolete due to regulatory, technological, or operational changes.

- Stay aligned with evolving accounting guidance.

Given the rapid advancement of AI technologies, interpretations of existing standards are ever evolving. It is essential to monitor developments in U.S. GAAP, International Financial Reporting Standards, and related industry guidance that might affect the accounting treatment of AI software and infrastructure costs. Consider the need to engage technical accounting advisers for assistance.

About The Authors:

Jennifer Dzierzak, CPA, is a partner in the audit and assurance group at Crowe. She brings deep expertise in financial statement and compliance audits, as well as acquisition and consolidation accounting for commercial organizations, with a particular focus on the life sciences sector. With more than 20 years of experience serving both public and private companies, Jennifer is well-versed in complex accounting and reporting matters and has extensive knowledge of International Financial Reporting Standards and U.S. GAAP requirements.

Jennifer Dzierzak, CPA, is a partner in the audit and assurance group at Crowe. She brings deep expertise in financial statement and compliance audits, as well as acquisition and consolidation accounting for commercial organizations, with a particular focus on the life sciences sector. With more than 20 years of experience serving both public and private companies, Jennifer is well-versed in complex accounting and reporting matters and has extensive knowledge of International Financial Reporting Standards and U.S. GAAP requirements.

Karen McDaniel, CPA, is a partner in the Crowe audit and assurance group with extensive experience serving life sciences and manufacturing companies across all stages of the business life cycle. She advises clients from early-stage development through IPO readiness, SEC reporting, and ongoing public company compliance, focusing on accounting for complex transactions and financial reporting matters. She has deep expertise in SOX 404 compliance, internal control design and remediation, and technical accounting under U.S. GAAP. Karen brings a disciplined, risk-focused approach to helping high-growth organizations meet regulatory and reporting requirements efficiently and effectively.

Karen McDaniel, CPA, is a partner in the Crowe audit and assurance group with extensive experience serving life sciences and manufacturing companies across all stages of the business life cycle. She advises clients from early-stage development through IPO readiness, SEC reporting, and ongoing public company compliance, focusing on accounting for complex transactions and financial reporting matters. She has deep expertise in SOX 404 compliance, internal control design and remediation, and technical accounting under U.S. GAAP. Karen brings a disciplined, risk-focused approach to helping high-growth organizations meet regulatory and reporting requirements efficiently and effectively.