Why Developing A Metrics-Driven Culture Is A Clinical Operations Must-Do

By Randy Krauss, head and executive director of metrics, analytics, and performance, Merck & Co., Inc.

When I first got involved in clinical operations 20 years ago, I sensed a reluctance and/or lack of interest across the industry in tracking operational metrics. You might say there was interest in what we did (tracking), but not how well we did it (performance). It struck me as odd that companies immersed in data to determine safety and efficacy would not be interested in using a different data set to support ways to conduct the trial in a more timely, efficient manner. After all, doing this would allow the sponsor to realize revenue faster.

The first metrics I collected and reported on were the various cycle times between key clinical study milestones at the study, country, and site levels. We did this, likely because the data was readily available, with the planned and/or actual milestones dates maintained in a project plan (centralized or decentralized). Many companies submitted this data to industry benchmarking surveys and were able to compare performance against our peers in a blinded way. We really couldn’t say if the performance was good, as we had no goals or targets, and thus it was simply informational.

A lot has changed since then. Time pressures, the never-ending need for resources, and cost constraints have forced us to make better decisions and defend them. The number of systems used to support the conduct of clinical trials has increased and the amount of data used to monitor our portfolio, studies, and processes has soared. While there is still value in using traditional dashboards and reports that tell us what we did, what we need to do (actions), or why it happened, the use of advanced analytics and RWD/E is enabling us to ask more sophisticated questions to be more predictive — what will happen — and prescriptive — how to make it happen.

Understanding Your Organizational Goals And Developing KPIs

If you asked colleagues gathered in a conference room about your organization’s goals or what’s important to the organization, it’s possible they could not articulate an answer. If you asked them what they wanted to measure, there would be no shortage of ideas. There is a tendency to want to measure everything. Like collecting study data, we often collect more data because it’s available and we may need it later. It doesn’t mean we are using the data in a meaningful or impactful way or asking the right questions.

If you and a senior leader stepped into an elevator, and you were asked how your group is performing, how would you respond? Some would share the status of that critical trial that just kicked off, while others would share the volume of work that was completed (i.e., 15 protocols approved, 10 regulatory submissions sent, or two inspections completed). The problem with those responses is that you didn’t answer the question, “How well did your group perform?” The responses explain what you did, but not how well you did it. The answer(s) to the question are your key performance indicators (KPIs) and should be aligned with your organizational objective(s) or goals. Some organizations identify KPIs based on a balanced scorecard approach1. However you identify them, it’s important to realize every metric is not a KPI, but every KPI is a metric that can be measured against a goal or target. While there is no magic number, five to seven KPIs often feel right.

Establishing KPIs And Other Worthwhile Metrics

All metrics are not created equal. If you ever built your own home, upon signing the contract, the builder will tell you how long (cycle time) it will take to build. To be honest, as the future homeowner, it’s not the most important piece of information, at least, to me. Whether it’s four months or eight months doesn’t matter. What matters most is the date I can move in. Knowing the date allows me to plan whatever I must complete before and/or after that date. Cycle times help me plan but delivering on time (timeliness) is more important to me than cycle times.

In our organization, the percentage of clinical milestones delivered on time is a KPI, but it only includes a select number of milestones, such as “last patient in” and “database lock.” It is a KPI because completing it on time is a commitment we made to the business, so they may know when they will get the first readout on the safety and efficacy of the drug, and to our patients, who may be waiting for a lifesaving medicine. Sitting below, or supporting those KPIs, are leading indicators that provide insight as to whether you will deliver those KPIs on time and, if not, determine the proper mitigations. Measuring whether sites are activated and subjects are randomized according to plan provides insight into whether you will deliver those KPIs on time and, if not, allow you to activate mitigation plans. A third level of metrics may include measures that support your ability to activate sites and/or randomize patients.

Another example of understanding the importance of aligning with organizational goals is when a function or group implements metrics and goals related to a key component of a process, i.e., signoff on site contracts. This would fall into the third level mentioned above: supporting site activation. With so many steps or processes involved in getting a site activated, and ultimately that last site activated, how does this one step help achieve the organizational goal? The goal may be to reduce the overall cycle time of our studies by 15%. The function may want to measure cycle time and reduce the time it takes to sign the contract by 25%, but this one process may not help you achieve the goal of reducing overall cycle time. It will require looking for opportunities to improve across many different steps or processes.

Acting As Both Data Providers And Data Consumers

Identifying metrics that are actionable and detailing how they can help meet organizational objectives are critical. By knowing what’s important and identifying the business questions that need to be asked, you will be able to determine what to measure, the data needed, and how to calculate it. The metric should be actionable to help realize those goals.

Once the metrics have been identified, next comes ensuring transparency and quality. Years ago, when I first started presenting metrics, a data consumer who also was a senior leader would comment to me that he had different numbers. After presenting the second time and realizing this problem was not going away, I came prepared with how the metrics were calculated and what data was included/excluded. With that transparency, he understood the difference, and there were no longer questions about the calculations.

With that solved, there were lingering questions on the quality of some of the data. While we always want good, clean data input into a system, we ask data providers to collect so much data that it is not always the case. They know their data better than anyone, but they may not be aware of how it’s being used and why. They may only find out when it doesn’t feel right to data consumers. Ensuring that data providers are also data consumers is one way in which to improve data quality.

Advanced Analytics Are Here

Today, advanced analytics and new data sources in the form of RWE (real-world evidence) are allowing us to bring even more value to the business using data. An example of using advanced analytics is in site selection. Using criteria important to us and operational data from the site, we can employ more complex algorithms to measure and rank a site’s/institution’s performance. These results can then be compared to rankings that are available externally across sponsors. The ranking, along with your experience with a site/institution, should carry greater weight than a ranking from an external vendor with an unknown algorithm. Another example is using RWE to identify geographies and even patients that are tailored to meet specific criteria. Data sets now available include those reporting diversity, claims, or laboratory data, along with indication-specific incidence and prevalence. Paired together, these data sets can help you decide whether to use a site and how to approach goal-setting with the site.

Identifying and implementing metrics alone doesn’t ensure success. An organization must be data literate regardless of whether it operates as a data provider, consumer, or both. Morrow defines data literacy as the “ability to read, work with, analyze, and communicate with data2.” The ability to do this is a critical success factor. Senior leaders must set the right tone for embracing the data. It should be used to celebrate our accomplishments and to identify opportunities to get medicines to the patients sooner.

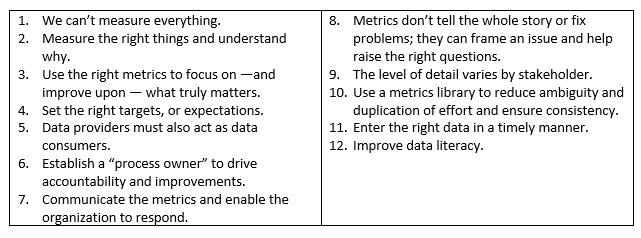

Guiding Principles For Collecting & Measuring Metrics

References

- Pharmaceutical Metrics: Measuring and Improving R&D Performance. David S. Zuckerman. (Gower, 2006).

- Be Data Literate: The Data Literacy Skills Everyone Needs to Succeed. Jordon Morrow (Kogan Page; 2021)

About The Author:

Randy Krauss is the head and executive director of metrics, analytics, and performance within the global clinical trial operations at Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. In this role, he and his group support the optimization activities of planned studies, as well as oversight of portfolio, studies, and processes. Prior to joining. Prior to joining Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA in 2016, Randy worked in similar roles at Genzyme (Sanofi), Shire, and Alexion.

Randy Krauss is the head and executive director of metrics, analytics, and performance within the global clinical trial operations at Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. In this role, he and his group support the optimization activities of planned studies, as well as oversight of portfolio, studies, and processes. Prior to joining. Prior to joining Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA in 2016, Randy worked in similar roles at Genzyme (Sanofi), Shire, and Alexion.

Randy began his focus on this research discipline at Genzyme, where he served as director of metrics, analytics, and performance. There, he led a cross-functional team to identify and maintain KPIs and other metrics to ensure operational success and compliance related to product development and support. Also at Genzyme, Randy conceived, developed, and maintained an enterprise-wide tool containing project status, timelines, and global development plans to drive the portfolio decision-making process. Randy also spent four years at the Boston University School of Medicine as a lab coordinator and a biochemistry instructor.

Randy received his B.S. from the State University of New York at Fredonia and his Ph.D. in microbiology from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He completed his post-doctoral fellowship at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in Worcester.