CRA Burnout: How Big A Problem Is It, Really?

By Fiona Wallace, director, FW Clinical Research Ltd.

Clinical research associate (CRA) turnover has long been a complex and challenging issue. We can recruit more CRAs, increase publicity in colleges, and introduce assessment standards. I could quote various statistics regarding turnover, but I won’t. This article is not about those things. This article is first in a four-part series that will look at how employers can make effective changes in the workplace that will empower both line managers and CRAs to take control of their own mental health resilience in light of their demanding role. A happier CRA is more likely to stay with an employer and will lead to greater productivity, resulting in better efficiencies within our clinical trials. To quote the renowned American thought leader on positivity psychology, Shawn Achor, “The greatest competitive advantage in the modern economy is a positive and engaged brain.”1

This article is the first of a four-part series that will investigate the disillusionment CRAs today experience with their role, why they do, and what we can do about it. I conducted a survey completed by 700+ CRAs, so let me start by explaining why I did.

An Inherently Stressful Lifestyle

The idea for this article came when I read a book by Stephen Ilardi, “The Depression Cure: The 6-Step Program to Beat Depression without Drugs.”2 I read this book because I have severe depression, and when you have depression you try to “fix yourself,” so you read a lot of self-help books. Due to my background in sciences and clinical research experience, the book made me think about how vulnerable CRAs are to developing mental health issues in the working environment.

The book outlines six key lifestyle elements that can protect against depression by reducing your stress-response-circuit activity. By reducing your “runaway” neurological stress response, you increase your resilience to depression and anxiety.

So, taking it back to the daily role of a traveling CRA, how are they at risk? Let’s briefly look at the six lifestyle elements researched by Ilardi:

- Exercise – This tricks your stress response into down-regulation. CRAs have a sedentary lifestyle due to office work and traveling. Reduced exercise does not lower stress hormones, so the body can remain in a fight-or-flight status.

- Natural sunlight exposure – Natural daylight is 100 times more powerful than indoor artificial lighting. The lighting levels have a direct impact on stress hormones and levels of vitamin D, and low levels of Vitamin D have been found in people with depression. Sunlight exposure allows our bodies to convert cholesterol into vitamin D3. CRAs monitoring inside, working in offices, and on transport may not get enough natural sunlight, so they are potentially at risk.

- Restorative sleep pattern – This is required for processing of neurochemicals accumulated in the day. CRAs’ sleep patterns can be affected by travel, staying in hotels, and workload. This was mentioned by some CRAs who completed the survey I conducted.

- Social connectedness – Brain activity is regulated by social connections. Periods of isolation can up-regulate stress hormones. CRAs who often work in isolation, are home-based, and travel have reduced social connectedness.

- Value-related activity – This is engaging activity related to your own personal values. If work takes precedent and you are unable to construct a meaningful work/life balance around your values, your stress response will increase.

- Omega-3 fatty acids – Studies indicate these help regulate brain function more effectively. Our bodies cannot make omega-3 fatty acids, and our diets do not provide the optimal omega-3 to omega-6 ratio necessary for antidepressant effects. The ratio should be 1:1 Omg3:Omg6. In the average diet, it is now 16:1, and this can affect a person’s stress-response resilience. CRAs may not be any more at risk of this than the average person; however, a CRA’s food choices may be limited when traveling, working late at the office, and monitoring on-site.

I remember what it was like to be that typically tired CRA — traveling on my own somewhere strange; tired; checking into a hotel room late at night; searching for some high-calorie, high-sugar processed snack in my bag; powering up my device to do some work (when it is already 11 p.m. and I need to be on-site at 9 the next morning).

The CRA Role — Then And Now

I was that CRA 15 to 20 years ago, and my on-site monitoring day looked like this:

- Review hard copy medical patient notes and source data, including patient diaries and questionnaires.

- Review the hard copy case report form and perform a source data verification check, noting any monitoring discrepancies.

- Visit the pharmacy, and conduct drug accountability. Return to the clinic for a short meeting with the site staff, hopefully the investigator! Go home; write the visit report and follow-up letter the next day. No mobile phones, no technology.

Nowadays, we may expect to see this type of daily routine:

- all of the above tasks, although now working on much more complex, higher-risk trials involving biological agents, rare orphan diseases, and advanced technology

- managing constant information notifications via mobile phones and other devices, i.e., we don’t stop working

- conducting teleconferences on the road

- more guidelines and documents to review in line with the risk-based approach

- perceived organizational and cultural expectations that multitasking and extreme busyness are now the norm and to be expected

- being out of the office for an increased number of days at a time (on-site visits).

I am not suggesting CRAs 15 or 20 years ago had it easier or harder than CRAs today. I am saying recent developments in the way employees work and the technology that has since developed are not conducive to good mental health, i.e., never completely switching off from work and increased expectations of multitasking. However, each trial is unique and affected by factors such as study training, user-friendly guidance documents, a good team structure with clear line-of-sight objectives, and feeling supported by management.

The Relationship Between Mental Health And Burnout

After reading the book, I was interested in how CRAs manage their mental health in line with their day-to-day roles. So, I conducted an anonymous survey with nine questions, the results of which will be revealed in the subsequent parts of this series. The survey was distributed via several forums, such as The Association of Clinical Research Professionals, Clinical Leader, a clinical research group on Facebook, LinkedIn CRA-specific groups, and my personal connections.

I vastly underestimated the huge response to this survey — over 700 responders from many different countries and organizations. There were no monetary incentives, just the chance for CRAs to provide their own perspectives and ideas.

For the majority, this survey provided an outlet for current difficulties our CRAs face in their day-to-day lives. It also prompted some strong feelings about what mental health actually is, e.g., a few responders were very unhappy I asked about mental health, as they feel it is a private matter and not related to burnout. I believe chronic stress can result in burnout and if burnout is left untreated, it can lead to a decline in your mental health.

What is burnout? Here is an explanation from Robert Ballard, head of the American Psychological Association’s Psychologically Healthy Workplace Program:3

“Burnout is an extended period of time where someone experiences exhaustion and a lack of interest in things, resulting in a decline in their job performance. A lot of burnout really has to do with experiencing chronic stress. In those situations, the demands being placed on you exceed the resources you have available to deal with the stressors.”

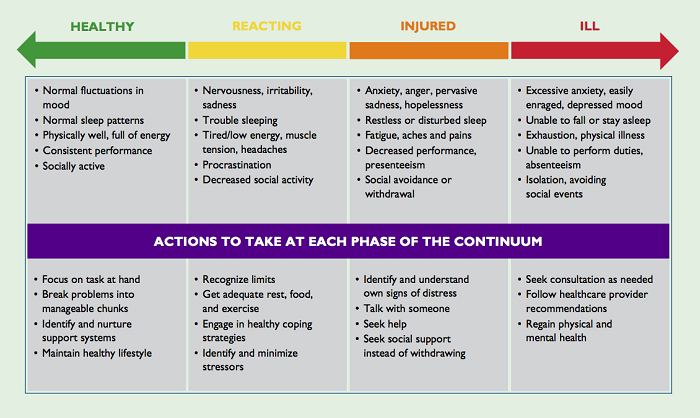

According to the World Health Organisation,4 overall health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. This definition was established in 1948 and has remained unchanged since. I believe any individual’s mental health is always in a fluid state, moving along a continuum.

So, where do you think a CRA should be on this continuum?

The answer is anywhere. No one “should” be in any particular zone at any dictated time. Where you are depends on you as an individual, your coping resources, and your external environment.

Figure 1: Mental Health Continuum Model5

It is important to recognize that someone with a diagnosed mental health condition can be in the healthy green zone, and someone who has not been diagnosed with any mental health conditions and was in the green zone two weeks ago can be in the orange or red zone now, perhaps due to a house move or database lock.

A 2013 National Survey6 found one in five Americans lives with mental illness. And, according to a U.K. survey conducted in 2017,7 three out every five employees (60 percent) experienced mental health issues in the preceding year because of work. Just 13 percent felt able to disclose a mental health issue to their line manager. Those who do open up put themselves at risk of serious repercussions. Of employees who disclosed a mental health issue, 15 percent were subject to disciplinary procedures, demotion, or dismissal. This also came up in the CRA Burnout survey.

As the statistics above show, there is much stigma surrounding mental health. Even more so in the clinical research industry, where importance is placed on being a productive, professional academic working to high standards within regulations, usually on a tight timeline.

In Part 2, we reveal what CRAs had to say about their jobs and their mental health. We will look at the answers to questions such as: If you have depression and/or anxiety, have you been able to inform your employer and/or your line manager? Have you ever left a CRA role because you were concerned your mental health would deteriorate?

Stay tuned.

References:

- https://www.ted.com/talks/shawn_achor_the_happy_secret_to_better_work?language=en&utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare.

- The Depression Cure: The 6-Step Program to Beat Depression without Drugs by Dr Stephen S. Ilardi.

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/learnvest/2013/04/01/10-signs-youre-burning-out-and-what-to-do-about-it/#2676937625b4.

- Preamble to the Constitution of WHO as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19 June-22 July 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 states (Official Records of WHO, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948.

- https://amiquebec.org/what-is-recovery/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings, NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014.

- https://wellbeing.bitc.org.uk/system/files/research/bitcmental_health_at_work_report-2017.pdf

About The Author:

Fiona Wallace, director at FW Clinical Research Ltd, has worked in global CRO and pharma for 18 years. Her experience spans many countries including India, South Africa, U.S., Europe, and Central and Eastern Europe in Phase 1–4 studies in oncology, ophthalmology, erectile dysfunction, and rheumatoid arthritis. She specializes in developing high value retention learning solutions by utilizing her breadth of experience in project and CRA management, global clinical regulatory training, inspection readiness management, and provision of client solutions to improve staff retention and engagement. Her latest project is to open up the discussion of mental health in the clinical research workplace, with the goal of improving the quality of life for everyone working in the spectrum of clinical research. Wallace can be reached at fmwallace3@gmail.com.

Fiona Wallace, director at FW Clinical Research Ltd, has worked in global CRO and pharma for 18 years. Her experience spans many countries including India, South Africa, U.S., Europe, and Central and Eastern Europe in Phase 1–4 studies in oncology, ophthalmology, erectile dysfunction, and rheumatoid arthritis. She specializes in developing high value retention learning solutions by utilizing her breadth of experience in project and CRA management, global clinical regulatory training, inspection readiness management, and provision of client solutions to improve staff retention and engagement. Her latest project is to open up the discussion of mental health in the clinical research workplace, with the goal of improving the quality of life for everyone working in the spectrum of clinical research. Wallace can be reached at fmwallace3@gmail.com.