Seriously … Are We Making Any Progress?

By Dan Schell, Chief Editor, Clinical Leader

I had to laugh when Norm Goldfarb of The Site Council asked the following question after Ken Getz’ presentation at DPHARM last week:

“Ken, you’ve presented all of this fantastic data over the years. Most of it is really depressing. How do you maintain your optimism in the face of all the data you're collecting?”

This got a chuckle out of Getz, who commented that he was used to those kinds of questions from Norm. But I’m guessing a lot of folks in the audience felt the same way about much of the data presented — it wasn’t very … let’s say, positive.

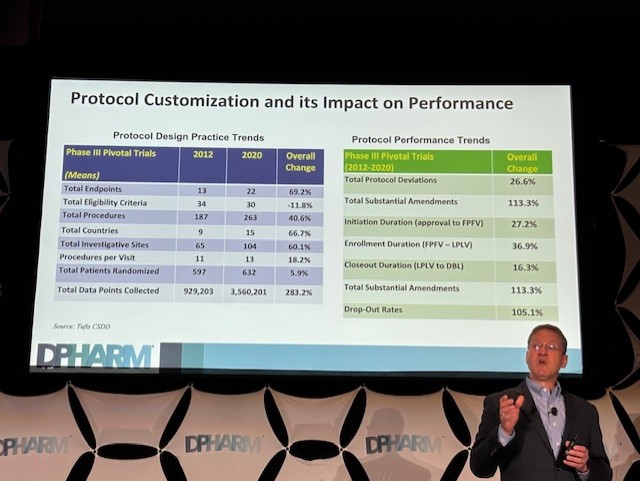

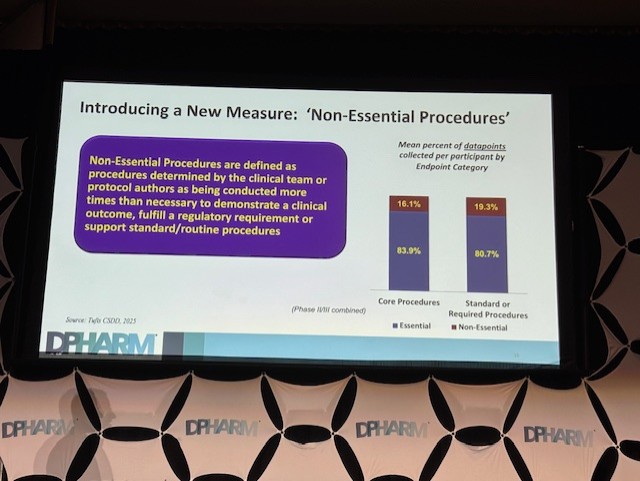

Getz, the Executive Director at the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD), presented findings from a study they did with TransCelerate BioPharma, which sheds light on the volume and purpose of data collected in clinical trial protocols. His talk centered on a fundamental paradox in modern clinical research: While we have an incentive to manage and optimize data collection, our protocols often accumulate an excessive amount of information that isn't directly relevant to demonstrating the safety and efficacy of a drug. This, in turn, contributes to a host of problems, from higher costs and longer cycle times to increased burden on investigative sites and patients.

Of course, none of that was probably a big shock to those in the audience, but seeing the data on some of those big slides on stage was a sobering way to start the morning of the second day of the conference. Especially the slide that showed that between 2012 and 2020, the total number of data points collected increased by 283%.

All of this really made me wonder to myself, “What are we doing here?” I mean, for years, we’ve been talking about how the over-collection of this “discretionary” data — that may provide strategic value for clinical teams — is a major driver of operational complexity. It contributes to a high number of protocol amendments, subsequent trial delays, and increased costs to trials. Getz even noted that as protocols grow more complex, they become harder to execute, leading to higher burdens on patients and sites, who are already struggling with staffing shortages and high turnover.

So is all this extra data and complexity worth it?

Leveraging New Guidance For A More Agile Future

Getz's presentation emphasized that these inefficiencies have a tangible financial and human impact. He cited a study that showed a significant ROI from using innovations like DCT components to shorten trial cycle times. The goal, he says, is to align the incentives of sponsors, CROs, sites, and patients to streamline operations without sacrificing data integrity or patient safety. Simple, right? 😃

The new ICH E6 R3 Good Clinical Practice Guideline can play a big role as a potential catalyst for the change we need in this area. The guideline encourages managing higher volumes of data through “agile and more flexible protocol designs.” I wasn’t sure what that meant, so I looked at the Guideline, and it very clearly defined agile and flexible.

Just kidding. It’s not clear at all.

It does say, “Building adaptability into the protocol, for example, by including acceptable ranges for specific protocol provisions, can reduce the number of deviations or in some instances the requirement for a protocol amendment.” That’s pretty close to, “flexible by design.” It means you can bake in leeway (e.g. windows, ranges) rather than rigid fixed rules. I also found this line: “Clinical trials should be described in a clear, concise and operationally feasible protocol. The protocol should be designed in such a way as to minimize unnecessary complexity …” Sure, your first response is probably, “No shit.” But this does nudge you toward simplicity, which is part of being “agile”, and it does remind you that overcomplexity will only slow you down or create more amendments.

The Guideline is also pretty subjective on what counts as “just enough data” vs “too much data”, and of course, it depends on the disease area, therapeutic context, regulatory expectations, risk profile.

Getz pointed to the guideline’s emphasis on RBQM (risk-based quality management) as a method to achieve what might seem like conflicting objectives: optimizing data collection while minimizing site and patient burden. By focusing on a risk-based approach, research teams can prioritize the most critical data and procedures, ensuring that resources are allocated where they matter most. This shift away from traditional, check-the-box methods is crucial for an industry struggling with operational inefficiency.

The Road Ahead For “Collaborative” Innovation

Getz concluded his presentation by looking to the future. He shared that a manuscript detailing the study's findings has been submitted for publication. The research team is now performing subgroup analyses and preparing follow-up papers to provide more granular insights. TransCelerate is also developing a tool and framework based on the study findings, which will be presented at an upcoming meeting. The goal is to continue socializing these insights and gather feedback from the industry, ensuring the findings lead to tangible changes in protocol design and data management.

And how are we going to do that?

Well, according to what I’m hearing as the new buzzword — collaboratively. It’s another one of those “no-duh” instances, like when everyone decided to start saying they were “patient-centric” or, now, “site-centric.” But don’t misunderstand me: I’m all for collaborating. I think this Tufts/TransCelerate study is a good example of collaboration, and I know that it’s ongoing. But I’m not sure any level of collaboration — however you define it — among sponsors, sites, and CROs is going to create less complex protocols with fewer nonessential data points.

Dammit! Norm was right, this is depressing.